We arrived on the coast of Iquique on the 9th April, 8 days after the 8.2 moment magnitude earthquake which had rocked the city, and after the aftershocks which included a 7.7 on the 3rd April. Once the pressure had been released from the two tectonic plates barreling into one another (the Nazca plate sub-ducting underneath the South American one), it seemed pretty safe to us. The tsunami warning signs we saw all around the town, and the fact that the center of town where all the affordable hostels and accommodations was right within the potential flood zones did not even put us off.

The people in Iquique looked much more traditionally indigenous – more like Bolivians and Peruvians – than the more Southerly cities. Especially the cities which were settled by European immigrants. Iquique did not have much to offer, however, as the museums and places of interest were all closed due to the earthquake. We were told that many of the buildings still had to be assayed by architects and specialists to ensure their safety before being reopened to the public. To put the earthquake into context, we saw a number of people who had been displaced from their homes living in tents in Iquique, either because their homes were destroyed, or because they were too scared to return to them. 80,000 people were displaced, and hundreds of women had escaped from a local prison when a wall collapsed. A small 2 meter tsunami struck the North of Chile, but we did not see any evidence of it. On the way to Iquique we passed through Antofagasta, but as it was the middle of the night, we saw no evidence of the earthquake there either, even though on the news some broken buildings and tsunami damage were featured.

We did mange to sneak into an old post-colonial period house on the main tourist attraction Baquedano Street, but were kicked out when the guard realized we were there – he showed us the cracks in the wall and some part of the ceiling which had fallen down when we played the ‘no hablo espanol’ card.

Iquique used to be Peruvian, in fact, but was annexed during the War of the Pacific. It’s wealth and status back in the 19th Century came from the Nitrate mines in the region (the reason for the war). The lavish features of these houses were all gone by the time we arrived – time and neglect had made the city look like just another typical Chilean third world city. We did try to see some pelicans and sea lions hanging around by the port but all there was were some rough sailor types, and a bad smell. One interesting thing we did see, was the Esmerelda ship that had been replicated exactly. This was the ship that the Huascar had sunk (the one we boarded in Concepcion), and that Arturo Prat had died whilst commanding. However, it was another attraction that had closed due to the earthquake.

Frustration was compounded when we tried to rent a car and started running out of time, but we finally found a good deal with Rent A Car Iquique. Not the catchiest of company names, but the people there were nice enough and their car, although not a 4x4, was what we needed to get out of the city and see the surrounding attractions. The tour companies had tours which were more expensive than renting a car, as not many tourists were visiting because of the quake, and they were unable to tailor the tours to what we exactly wanted anyway!

We got our Hyundai Avante, and headed out from the city pretty early. Unfortunately, we did not reckon that there was only one road out of town and it had been narrowed down to only one lane due to earthquake damage. They let the stream of traffic come into town for twenty minutes, then the cars go out for twenty minutes. It took us over an hour to get out of town, so we had to rush around a little bit, but still made it to the places we wanted to get to!

Our first stop was to drive East towards the main route 5 which cuts through Chile North to South. We arrived at Humberstone after numerous confusing detours past roadwork after roadwork. The town of Humberstone was a saltpeter works that had since been long-abandoned when the industry collapsed. Saltpeter is basically a collection of nitrogen-containing compounds which includes Potassium Nitrate and Sodium Nitrate. Used as fertilizer and explosives, the boom in Northern Chile began in the 1870’s, when Northern Chile was still Peru. James Humberstone, who the town was later named for, founded the town of La Palma, which was owned and administered for the Peru Nitrate Company. The town’s buildings are set in the English style of the time, and nowadays it is a large ghost town, complete with church, hotel, worker’s houses, and main plaza. The saltpeter’s works are extremely close to the town, and with the use of a little imagination you can see the people walking around still working there. In fact, many of the object that were used in the town are set out in various houses and locations in the town.

Humberstone muse have been an extremely polluted place to live, being so close to the saltpeter mine. There were around 200 of these mines in the region, some doing better than others. Humberstone himself introduced the Shanks process of saltpeter extraction, which enhanced production and made the works extremely effective.

It was strange walking around a ghost town so large as Humberstone. The nearby Santa Laura works 3km away were equally as strange, but they were only a saltpeter works and had none of the rows of houses that Humberstone had. All of the works in the area dug up the Caliche, or sedimentary Calcium Carbonate, and this boom lasted up until the First World War when Europe started to produce saltpeter in huge quantities, and Germany began to produce it artificially.

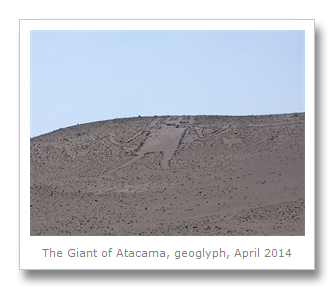

Once we had left (Humberstone is extremely hot an dusty, even in the morning), we left to go and see a huge geoglyph – the Atacama Giant. Located at Cerro Unitas, or Tarapaca, this huge figure is the largest anthropomorphic geoglyph (a design made with durable rocks) in the world, and one of around 5000 that have been found in the Atacama from various cultures including the Tiwanaku and Incas. There are numerous theories as to what these geoglyphs mean, ranging from images of deities, calendars and even maps. Maybe they are just expressions of art?

We decided to head back the way we came and drove back to ruta 5 via Huara, the town at the turning for Cerro Unitas. When we got to Huara however, we were further delayed by loads of soldiers who had closed the road. A police helicopter then proceeded to land in the middle of the road! We had to wait, along with a growing number of vehicles whilst some minister did a visit to the town, then got in a car and zoomed off! A few minutes later some convoy arrived with emergency earthquake relief from the rest of the country, which it seems the minister wanted to be there to meet for the cameras. Why they did not land by the side of the road we will never know.

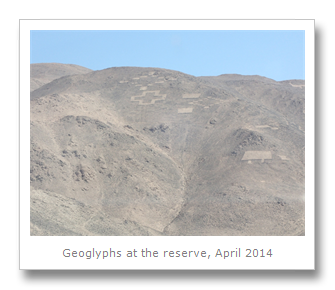

We eventually set off again, and drove down to Pampa del Tamarugal Reserva Nacional. We stopped off at the park ranger station, CONAF, where no-one seemed to be working, Eventually a socks and sandals kind of guy gave us directions to the geoglyph sector of the park, and off we went. We arrived after driving down a 2km long dirt road, an arrived at a checkpoint which was closed. We pretty quickly worked out that the park was closed – but as no-one was there, we opened the gate and drove in anyway.

The road snaked around a set of small mountains, upon which Francesca was looking for geoglyphs whilst I was making sure the road was OK after the earthquake. Bingo! We finally found the set of 350 plus geoglyphs and proceeded to park and walk along the (earthquake damaged) trail to view them. Most of them were huge, many meters long or high, and they were all over the hills.

Llamas, circles, spirals, and various seemingly abstract shapes are all formed on the mountainsides. The people who lived here made these hundreds or even a thousand or more years ago by clearing and placing stones, and the dry weather and temperate climate have conspired to protect them since then.

There are some odd shapes on those hills, and many interpretations have been presented by anthropologists an historians alike, but no-one really knows what they are or why they are there. And we got to see it for free!

We also saw the tree the reserve is named after, the Prosopis tamarugo, which is in the pea family. It only grows here naturally, and gets it’s water solely from dew in the air. The seeds are apparently used for goat food, but from what we have seen, goats will eat anything anyway!

We drove a bit further away from Iquique to a small satellite town famous for being an oasis in the desert that produces some amazing lemons, used in the rest of Chile in the drink Pisco Sour. Pica is a small town with just about 5 or 6 thousand people, mostly working in agriculture. We drove around for awhile looking for the communal thermals, a natural spring that is around 40C. Failing to find it, and realizing that we had to get the car back, we sped back towards Iquique, and lo and behold, traffic was stopped again on the way back, this time by soldiers who got a military helicopter to land in the road!

We still have no idea what that was about, but I ended up pulling the car off the road and driving around this obstruction in the middle of the desert! Weird.

We got back with 5 minutes to spare on the clock, and headed back to the hostel in a collectivo. We had bought some Chumbeque biscuit, which was basically a delicious biscuit made from flour, egg, sesame, cinnamon with layers of orange. They have different flavors, like honey and fig – all delicious. We got ours for free too, as the gay guy behind the counter tried to get my number with free Chumbeque!

We left Iquique the next day on the 12th April heading to the Northernmost Chilean city – Arica. We had travelled all the way from the South to the North by only bus, car and boat – all overland. On our way out of town, we saw from the second floor of the bus just how badly the earthquake had actually damaged the road!

No comments:

Post a Comment