The Chachapoyas culture is named after the Quechuan words for ‘cloud people’, and it is no wonder, as they were located in a beautiful area of North Western Peru, which is covered in high altitude forests. The bus trip from Cajamarca was a little crazy, as are most journeys in Northern Peru, especially when crossing the mountains. A stop in the jungle lowlands saw a complete change in humidity and temperature which we thoroughly enjoyed before heading back up into the altitude of the next mountain chain. We arrived in the fairly isolated city of Chachapoyas (named after the culture) and we looked forward to seeing some of the ancient ruins and waterfalls the area is known for.

Located between the Cordillera Central and the Cordillera Oriental, the area only receives moderate rainfall, and therefore has what is known as ‘transitional forest’ between the high altitude forests of the mountains, and the rainforest of the lowlands. In fact, the city is the capital of Peru’s Amazonas region. It was founded in 1545 when it was settled at it’s present location after moving several times due to bad climate and disease.

The city lies along the Utcubamba River which irrigates much of the crops in the region such as maize, banana, rice, sugar cane, orchids and coffee. The area was completely destroyed in a 1928 earthquake but has rebuilt itself rather successfully and is now enjoying a minor tourism boom.

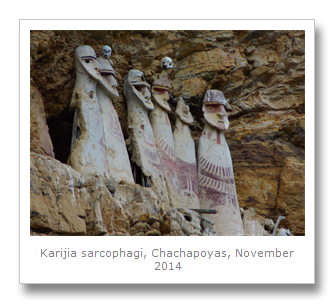

We organized some tours (Amazon Expedition) in the region at one of the many tour companies surrounding the main plaza, as they were pretty reasonably priced. The main things we wanted to see were the unique Chachapoyan ruins and tombs in the area, and our first trip was to the Quiocta Cavern which was used by the indigenous people as tombs. This tour is coupled with a visit to the unique and fascinating Karijia sarcophagi which the Chachapoyas built halfway up a mountainside.

The Quiocta cave system is extremely large with many stalactites and stalagmites all over the place. Boots are essential here because the cave is very wet and muddy. It is also advisable to bring a flashlight as the guides are pretty useless in this department.

We saw some bats flying around, and near the entrance there are some Chachapoyan bones and a large ceramic mask watching out over the cave entrance. A choice between the Quiocta cave and the Town of the Dead is made difficult as tour companies do not like taking people to the more difficult to reach Town of the Dead. Middle class Peruvian tourists do not enjoy walking much, it seems, and so the tour companies stick with the cave visit. We thought it was pretty cool, but it does get some tepid reviews.

After the caves, we bused to the site of the Karijia sarcophagi. It was not far, and the roads were OK, but the walk down from the nearby agricultural village was a pretty long way. Luckily it had not rained and so was not too muddy, but it was a long, rocky and pretty steep walk. There are horses you can rent to take you down and back up though.

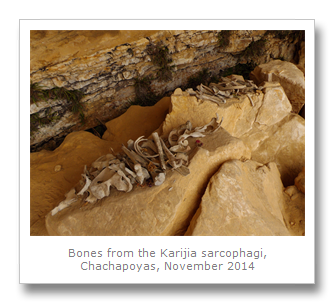

Called purunmachus, the sarcophagi have been dated to about the time of the Incan conquest of the area. There were originally eight sarcophagi, but some were damaged in the 1928 earthquake, and one even fell off of the cliff face. They are located halfway up a sheer cliff face at the bottom of a gorge and so are pretty inaccessible, which also means grave robbers have left them alone – which may have been the intention behind putting them there in the first place.

The sarcophagi are made of clay, and are painted white with red decorations, including male genitalia, indicating the corpses inside are males. Some even have human skulls placed on top of them, although it is unclear whether this is how the Chachapoyas left them, or whether the skulls were put there later.

A little trail leads along the bottom of the cliff to a small waterfall where a bunch of the bones from one of the sarcophagi lies. From here also, make sure you look back and see the other sarcophagi that are not the ones on the publicized pictures of the place. These are basically a wall made from the same clay, covering a little niche in the rock face, presumably with bodies buried behind it. They do present quite a bit of damage, though, with a few holes here and there.

We also noticed one other little tomb that only had one mask on it, which did not seem damaged at all. This one is a little more hidden by some grass and so is much harder to see, but the guides should know where it is.

We rented the horses from the bottom to take us back up the steep hill to the village, where we bought a nice souvenir – a wooden statue of one of the sarcophagi - carved, painted and lacquered by a local artist.

It is believed the sarcophagi’s design was influenced by the more coastal Wari culture, who were the Chachapoyans rivals, and it is also theorized that the Chachapoyans placed their sarcophagi in this fashion to hide them from the Wari or their later conquerors, the Inca.

The next day, the 12th November, we took another tour. We got picked up from the main plaza of the city which is where all of the tours leave from, and we headed off for day two in the region.

We briefly stopped at a small Chachapoyan site which is believed to be a village of some sort. Incans took this site over when they conquered, and from across the valley at our viewpoint, we could see Incan architecture that had been clearly added to the structures there.

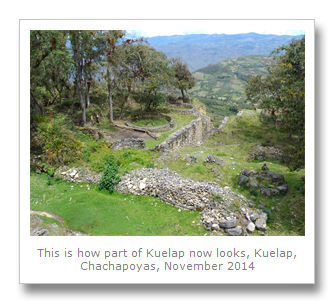

We continued South, along the Utcubamba river, to the ancient fortress of Kuelap. Often referred to as the Machu Pichu of the North, the site is fairly large, running about 600 meters by 110 meters. It is a stone fort, built around the 6th century (according to carbon dating), possibly to defend Chachapoyan territory from the Wari culture, or to simply aid in overseeing their own territory.

The site was all but forgotten after colonialism, only mentioned in four Spanish texts, until it was rediscovered in 1843 by a local judge. Kuelap is located near the present day town of El Tingo from where the judge hired mules and local guides to take him to the site. These days, there are still places to stay in El Tingo for people who wish to visit Kuelap on their own steam. The tours are pretty cheap from Chachapoyas though, although we did end up ditching our guide at the ruins because his explanations of the site were ridiculous. In fact, even the information boards had imaginative explanations about the site that were clearly attempts to elevate the importance of the site, with very little evidence to corroborate the proposed theories.

Built on top of the La Barreta mountain at 3000 meters above sea level, Kuelap is clearly a defensive fort. Most of the sides of the fort are surrounded by sheer cliffs, with just one heavily defended side being the entrance from the ridge it sits upon. One entrance, to the South, is built like an alleyway with high defensible stone walls that narrows at the top, only allowing one person to enter. Archaeologists have speculated that the ‘V’ shape of this alleyway represents fertility (in the shape of a vulva), which is ridiculous – it is obviously the way any sensible defending force would funnel possible attackers to a single point to be dispatched from the high walls above.

The site is now overrun with the cloud forest trees, orchids and bromeliads that fill the region, but the trails and important buildings running through Kuelap are well maintained, giving the place an Indiana Jones feel. In fact, in the movie The Raiders Of The Lost Ark, it is a Chachapoyan temple that Jones steals the idol from at the beginning. Grave robbing at it’s most romantic.

Most impressive are the views out across the jungle from Kuelap. That and the irrigation / drainage system that the Chachapoyans built. Unfortunately, this system was not maintained and therefore water build-up has caused the mound underneath the whole structure to swell, causing damage to the fort.

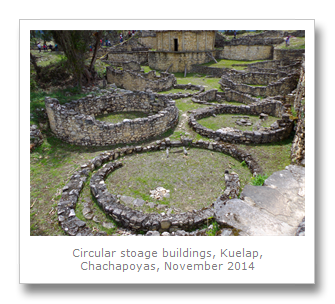

Like many South American archaeological sites, Kuelap has been attributed as having defensive, military, administrative, palatial and religious significance. These general suppositions come from meager evidence which can be interpreted many different ways. What we do know is that there are three different levels or platforms at Kuelap which all have circular towers. These defensive towers are impressive, as is the reconstruction of the circular dwellings found at the site, and the museum on site tells of how the place was built over many centuries.

The Inca also used the fortress themselves, as they did with many of their conquests. They built a rectangular building that we have seen in many other Incan sites that traditionally acted as a barracks and armory.

The Incans did have a lot of trouble conquering the Chachapoyans as they were such fierce fighters, but they did eventually manage it around the 1470’s. In fact, Chachapoyas was probably an Inca Quechuan term to tie together the egalitarian people of this region for administrative purposes. The Chachapoyans were probably a very loosely tied together collective of peoples who worked together collectively, when circumstances demanded it.

Once the Incans had put down the Chachapoyas rebellions, they deported many of them under their system of mitma, or forced resettlements. The Chachapoyas were then forced to fight against each other as the Incan civil war raged between 1529 and 1532. It is no wonder then, that the Chachapoyas eagerly joined the Spanish when they arrived to ensure the Incans were driven from their land. Better the devil you know, though, as it is estimated that over 90% of Chachapoyas indians died from diseases bought by the Europeans. Further forced resettlement by the Spanish has seen the Chacha language go all but extinct. The few words that we do have, particularly surnames that still exist today, point to an ancestry of Jibaro (Shuar) origins, which means the Chachapoyan ancestry came from the jungle.

Some people even believe that the Chachapoyans were descendants of Vikings. The people in the region are certainly quite fair skinned, but we did not see any of the blonde haired people that the Spanish chronicler Cieza de Leon wrote about. His writings were picked up by the Nazis however, to ‘prove’ that it was the Aryan race that bought civilization to the Americas.

Before we left Kuelap we noticed many different carved faces into the stone walls. One of the inverted towers apparently had some burials found in it, which is believed to be evidence linking the building to having a religious and ceremonial function. The ceramics of the Chachapoyans never did reach the same quality found in coastal cultures, but they made up for it with their buildings and tombs which are extremely interesting and unique.

On our last day we decided to head down to the neighboring town of Leymebamba where a museum displays exhibits on the region and other more inaccessible Chachapoyan sites such as Condor Lagoon and Gran Pajaten.

The Laguna de los Condores, or Condor Lagoon, is a two or three day hike to a lagoon which is surrounding by chulpas, or mausoleums, that held Chachapoyan remains. Inside each tomb is a seated mummy, but the tombs held little in the way of gold or silver. That did not stop local people from plundering the sites when they were discovered in 1996, and after the men (who worked for a cattle rancher) had already hacked away at the corpses with machetes, an argument led to police intervention and multiple arrests.

In this case, it is not just locals who did the looting, but hikers and tourists. After archaeological excavations, however, the mummies are now relocated in the Leymebamba museum, where we viewed them in their temperature controlled room.

The other site, Gran Pajaten is located deep in the Andean cloud forests of the Rio Abiseo National Park, to which you have to take cars and boats. Permission is hard to obtain, and we were told differing stories about whether the site was open to the public or not. Excavations in the 1960’s and 1990’s that cleared the site of vegetation for further exploration and possible tourism damaged the Chachapoyan structures irreversibly, as the vegetation was actually protecting many of the stone buildings from collapse. Maybe we will be able to visit this site in the future?

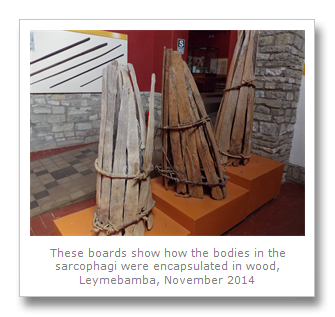

Bone flutes, basic ceramics and some excellent models of the Chachapoyan tombs and sarcophagi are found in the Leymebamba museum. It was well worth the visit, although infrastructure here is terrible, and so buses are infrequent enough to have left us stranded in the city with no way back to Chachapoyas. We had to pay for a taxi, and we found ourselves back in town with enough time to visit the only museum there (salas de exposicion Gilberto Tenorio Ruiz), which is just two small rooms with a few Chachapoyan ceramics and mummies. One mummy there does show how the bodies are placed in a seated position and then surrounded by planks before being encased in the clay sarcophagi.

Apparently only 5% of the ruins in this region have been excavated or even rediscovered from where they are simply mentions in Spanish chronicles. The Peruvian government have a lot of work to do to get tourism up to scratch here. With only one road running through the region that has minimal public transport, and many sites having steep and muddy climbs, difficult access means that this region may never be the Machu Pichu of the North, but it damn well should be!

There are many sites to see that we did not have time for, including walks to various waterfalls, ruins and rock paintings and petroglyphs. We will definitely be coming back to this region for more, and if we could do it again, we would have stopped briefly in Leymebamba before going on the Chachapoyas, and then would have spent more time there – particularly to look at the Condor Lagoon, Levanto, and spend some time trying to find the marvellous spatuletail hummingbird.

No comments:

Post a Comment