We left Casma in the Ancash region of Peru by shared colectivo (minivan) where we had to change for a bus in Chimbote for our onward journey to Trujillo. We foolishly decided, in Chimbote, to go for the faster and slightly more expensive option of a shared car. The driver had a death wish, and drove like a maniac, and we had to ask him to slow down before he killed us all. That guy will either be dead or in prison before we get home if he keeps driving like that.

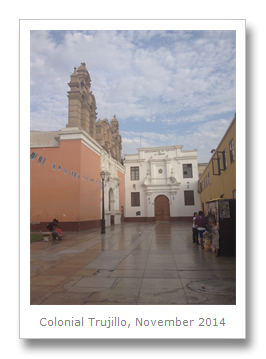

Luckily, we managed to safely get to our destination, and we found our way through the sprawling behemoth of Trujillo, Peru’s second largest city. The city is difficult to navigate without a taxi, and so we headed for the main plaza, the plaza de armas. We immediately found a tour agency (Planet Tours) located right on the plaza, and booked ourselves on the tours available. They were pretty good deals, and we also negotiated the price down a little.

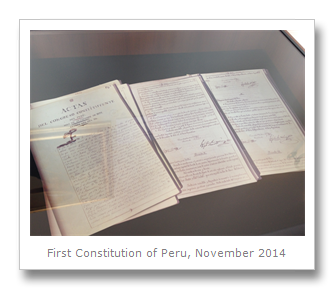

Trujillo is the capital of the La Libertad region, which was named for when the city’s mayor José Bernardo de Tagle declared independence from Spain in 1820, paving for the way for the Peruvian country. South American legend San Martin was the instigator of the revolution, coaxing de Tagle to announce the region’s independence, and Spain lost a huge swathe of its land in South America as their attention was diverted to the Napoleonic wars at home. Trujillo has since officially been honored as ‘faithful to the fatherland’.

We found Trujillo to be a little overpriced in the center, and so we stayed at the cheapest hostel we could find, Hospedaje Conde de Arce. It was a bit of a flophouse, but suited our purposes even though the walls were paper thin. It turned out to be a perfect location anyway, as pretty much all the tours in Trujillo are arranged on behalf of the Colonial Hotel, which was just one block away, so we didn’t have far to go the next day.

On the 2nd November we went on our first tour. The weather was really nice the whole time, and Trujillo definitely has earned its name as ‘the city of the eternal spring’. Located on the banks of the Moche river at the end of the Moche valley, the Trujillo area was home to the Moche culture between 100 and 800 CE. These coastal people left behind plenty of evidence of their passing, including ceramics, metalwork, and huge constructions made of adobe. Most of these constructions, including dwellings and temples, have been destroyed by looters and the passing of time, but the ones that are left are pretty impressive to visit.

The Moche culture descended into chaos sometime around 700 to 800 CE, and from their ruins a new culture sprang up with similar styles and techniques and behaviors. This culture was named the Chimu culture (900 CE to 1470 CE) whose people lived in the land of Chimor - which was basically the same area as the Moche people before them, but ran a little farther South after they expanded through conquest. This is evidenced by stories passed down to the Spanish from the Incans who eventually ruled this area when they subjugated the Chimu, and by archaeological evidence of the Moche having burned their cities and temples to the ground at around 800 CE.

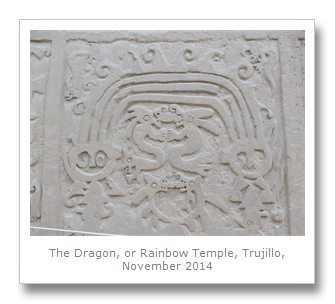

We first visited an old Chimu site called the Temple of the Dragon, or Temple of the Rainbow (Huaca del Dragon / Huaca del Arco Iris) found on the outskirts of Trujillo, dated by some archaeologists to the Chimu culture, around 1100 years ago.

Most of the other passengers on our tour were Westerners, which was a nice change as it meant we finally had an English speaking guide. Also, having seen South Americans litter in their own national parks and carve their names on treasured rock faces that are millions of years old, all whilst they pay a small percentage of what we are asked to pay for entrance fees to many of the attractions, it was also nice to feel that we were in a more respectful group of progressive Westerners.

Not so. A German guy in the group immediately dragged his finger down the adobe wall of the temple leaving a huge mark. What an idiot. Its bad enough that these temples have to contend with looters, El Nino weather conditions, pollution and the local population dumping their trash outside – disrespectful idiot tourists is the last thing they need.

The Dragon Temple is a typical pyramid shape, which had been the architecture of choice for thousands of years, but what made this one stand out was the intact state of the unique carvings found on the walls. Human figures sit alongside fierce looking creatures all portrayed under what is believed to be a rainbow. However, I think that this ‘rainbow’ looks more like the famous double headed serpent that is often depicted in South American cultures’ mythology from the Aztecs to the Incans. It is not eating its own tail in the classic pose that symbolizes the cycle of life, death, or rebirth, instead it is chomping down on two seemingly unsuspecting humans.

Another double headed creature is depicted below this scene holding a tumi knife in its jaws. Of course, the whole scene is open to interpretation, with the rainbow theory being the most popular. The ‘rainbow’ doesn’t have seven bands though, and as all the color has faded away now, it is hard to see how that explanation holds any water.

We proceeded to the top of the temple up a steep adobe ramp which the Chimu had built. From there we had splendid views of the mountains, and the dumpy neighborhood of La Esperanza, where the temple resides. Between the main portion of the temple and the outer walls were some huge and enclosed rooms. The explanation given by the guides of today is that these were used to store food, because grains were found in them. Again, this explanation did not make sense. Why store food in an enclosed room with no entrance or exit, in a temple such as this one, surrounded by carvings of fearsome creatures? You can decide for yourself – but it is essential to question every bit of information that is given about these pre-Hispanic cultures, as most of the facts can be re-interpreted from the data in front of your eyes, usually much more sensibly.

The Dragon Temple only takes about half hour to visit and appreciate. After this, we were whisked up and taken to our next stop of the day, the Esmeralda Temple. This temple is found about 2 km West of the city center and is another Chimu Culture building. Believed to be a dwelling of some Chimu lord, the site has similarities with the Chimu capital, Chan Chan.

The carvings at the Esmeralda Temple are geometric patterns, but there are some zoomorphic figures here too, a little like small dragons, but explained rather ludicrously as squirrels by our guide.

The stand out feature and figure of fun at all of the temples in Peru, are the Hairless Dogs. There are three types of Hairless Dog, Chinese, Mexican and Peruvian. All other types have gone extinct, and the Peruvian dogs we saw did seem to be a bit cross-bred by modern breeds as they were displaying hair in various places. One dog at Esmeralda did seem to be totally hairless, though, and we thought that he was awesome!

The temple itself is now named after the farmland that was founded here after colonization and the original name has been lost, or forgotten. It has two levels, with ramps connecting them that we walked up and explored. On closer inspection, some small fish carvings where found in between the geometric diamond patterns, making them appear as fishing nets. This also corresponded to carvings found at Chan Chan.

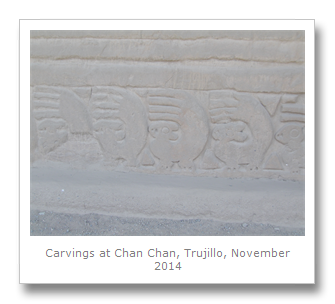

The old Chimu capital of Chan Chan is located West of Trujillo, and was our next stop of the day. Unfortunately, it is now cut in half by the Pan American Highway, which does not seem to care too much for archaeological sites at all (Sechin Alto, Manchan and even the Nazca lines were all split by this road – even an ancient site of whale fossils was partially destroyed in Chile).

The tour first took in the excellent Chan Chan Museum located at the site itself. We learnt a lot more from the information boards than from our substandard guide, and so we ditched our group.

We found out that the Chimu Culture consisted of a multiethnic group of peoples, all of whom spoke different languages (Sec, Olmos, Quingnam, and Muchic) which are now either extinct, or nearly extinct, thanks mostly to the colonization by the Spanish. Chimor itself was born from the dying remains of the previous Moche culture whose cities and temples fell into ruin around 800 CE.

The Chimu all-black ceramics fared a little better with many beautiful examples lasting until now. Domestic and ritual ceramics are distinguishable by their unpolished or polished finishes, respectively. Vast amounts of pottery were made, probably in ceramic centers that were like factories, where they used molds to churn them out, and patterned rollers to add decoration rapidly.

The social structure of the Chimu looked like the pyramid buildings that they left behind with a cacique ruler at the top, and peasants and slaves at the bottom. The administrative function of the leaders was to distribute goods, legislate and militarily protect the populace and increase the borders of Chimor by force and warfare.

Chimu cities like Tucume, Farfan and Manchan all acted as provincial centers of control, whilst Chan Chan was the capital. It was located at the border of the Moche valley, and ran from the seashore to 3km inland. In fact, this city is believed to have been the capital of Chimu for about 600 years, until Inca Yupanqui conquered the Chimu in 1470 CE. The Chimu were the largest empire to be conquered by the Inca, and so the Inca had to crush any possible rebellions. This was done with mitmas, or forced relocations to far-flung corners of the Incan empire.

The Chimu were experts at irrigation – they had to be with so little rainfall in the desert climate. The museum even spoke of a channel that was dug for 84km from the Moche valley to the Chicama valley for agricultural purposes.

Fishermen are believed to have lived separately from the general populace, and the sea was both revered and resourced. We know about the Chimu fishermen from the traditions that continue to this day, and from the pottery that depicted many sea resources from spondylus shells and sea lions to sea cucumbers.

Fueling the modern day grave robbers, the Chimu had made numerous metal works using copper, silver and gold. The advanced techniques are still used today, and the Chimu metal pieces are considered very fine, delicate and of high quality. As usual, much of what we know about this culture is from graves and funerary bundles, which is why it is so important to protect them from further looting by grave robbers. Most graves had offerings in them, such as ceramics, metals, fabrics and even food which tells us how the Chimu dressed and what they ate.

There were some nice models of the complex, and an explanation that there were several temple sites that made up parts of Chan Chan. These temples are believed to have been built when a cacique leader died, and he was buried there with much fanfare. We visited the complex of Tshudi which was the only one open to the public when we visited.

The UNESCO World Heritage site of Chan Chan has burial chambers, reservoirs, temples and houses. The most interesting parts are the murals and carvings on the adobe walls which have survived. Fish net carvings similar to the ones at the previous temples were all over, including the ones explained as being squirrels. There is a huge relationship with the sea with these sites, and these squirrels looked more like sea lions to me. Fishes, nets, cormorants and pelicans were all depicted, and we even saw the tomb of the cacique that was buried in that particular temple complex.

Our next stop of the day was a lunch break in Huanchaco which is a beach resort very popular with surfers and hippy travelers. We saw the caballitos de totora rafts made from woven reeds that have not changed since Chimu times, and are still used by fishermen today. They are made from the same reeds used by the Uros people in Lake Titicaca.

We ate ceviche (which is thought by some to have been invented in pre-Hispanic Huanchaco itself) had a local beer, and enjoyed watching the sea.

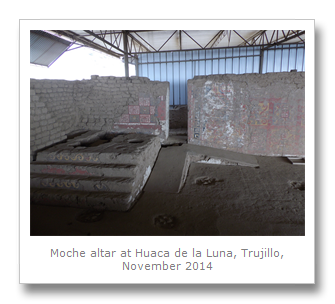

Our last stop of the action packed day was to visit Moche which is a small village to the East of Trujillo near a mountain called Cerro Blanco. This is thought to be the location of the Moche capital city, with two main temples – one dedicated to the sun and the other to the moon.

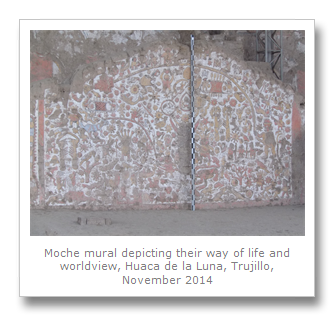

Looted for over a thousand years for gold, the Huaca del Sol (Sun Temple) has not yielded much archaeological evidence, and is in a very bad state. Visitors are not supposed to enter or stand on this temple (although we saw Peruvians doing so). The Moon Temple (Huaca de la Luna) was left relatively untouched though, and we spent some time viewing the murals which have retained their red, yellow and black colors from over a thousand years ago!

We climbed up to the Moon Temple and saw that the museum on site had been built in the style of Moche residences, retaining the same styles and colors believed to have been used in the period.

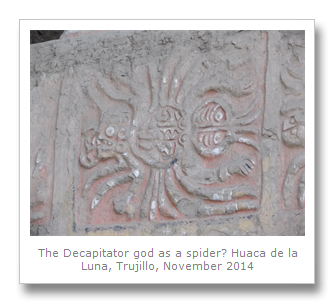

The adobe temple itself had many carvings and reliefs of different strange and wonderful creatures. It is believed the building was a religious temple and a place of pilgrimage, and there were many images of a spider figure which is believed to be a deity called the Decapitator. Often depicted as a human with a tiger’s snarl, this god holds a knife in one hand, and a severed head in the other. Bodies have been found showing indications of ritual sacrifice and even torture. The findings of these bodies have helped develop theories as to why the Moche culture collapsed. Ice core samples show that huge climatic changes were underway around the end of the Moche culture, and it is theorized that the Moche sacrificed people for a stable climate. Once the weather became so bad over a thirty year period, people lost faith in their gods and in their leaders, eventually setting fire to the temples.

The three platforms of the temple have different murals. Some of the levels contain tombs of high ranking people, and on the patios of the temple, the sacrificed bodies have been found. A staggered pyramid of different colorful carvings show dancers, warriors, the Decapitator god in spider form and snakes / dragons.

Great views of the valley and the surrounding ruins can be seen from the Moon Temple. Much of the old Mochica residential zone is now under the sand, but holes all over the desert evidence the presence of grave robbers. The Sun Temple now just looks like a huge mound of dirt after much looting, especially after the Spanish diverted the Moche river to facilitate the finding of gold there. It has been estimated that 2/3 of the structure has been completely lost.

The valley of Moche, not far away, was a sea of green in the desert where the locals grow sugarcane and asparagus.

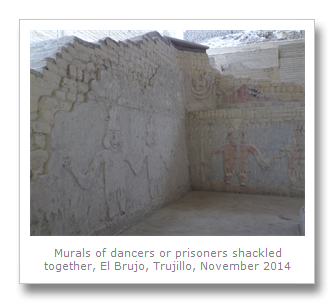

The next day we headed to another important Moche site, 45km North of Trujillo, where we learnt the latest archaeological beliefs that this culture had many priestess rulers. One pyramid yielding up its evidence is the El Brujo complex, whose name means ‘witch doctor’; so called for the many healing shamanic rituals believed to have been performed at the site.

In 2006 the Lady of Cao was found at this site, and with her discovery came the belief that the Moche had female rulers. This seems a bit of a stretch to me, but the body was found with numerous ceremonial items, and was tattooed and wrapped in cloth. Her large nose piece was worn over the mouth, some argue, to hide the expression on her face from her underlings. We were unable to take pictures of the pieces in the museum, but they consisted of a wooden idol made of lucuma (a fruit tree), a turquoise and shell spear thrower and even a small model of the temple built by, presumably, the Moche themselves. She also had a necklace with gold monsters with turquoise blue eyes that was found.

There are two temples at the site, both built in an additive fashion with new layers being plastered over the top of older ones between 1 CE and 600 CE. Some reliefs at the temple looked very similar to the Moon Temple reliefs, and the bricks also held a similar feature to other Moche sites: individual carvings on all of the bricks that make up the temple. It is thought that these carvings differentiated the builder – maybe to show how many bricks each one had produced, for payment or some other reason.

One relief shows a cup bearer offering the cup to an important ruler figure. It is thought that this cup bore the blood of ritually killed people that the ruler would then drink. Perhaps this is how the people sought to appease the gods who controlled the weather and the harvest? They obviously had no idea about El Nino back then.

It is sometimes surmised that the Lady of Cao is the cup bearer, but no-one really knows who she is – only that she died in her 20’s, probably due to complications during childbirth, although no baby was found. It is apparent that the Moche re-opened the graves of their ancestors, treating them to a change of clothing and some drinks of alcoholic chicha – possibly a little like the day of the dead in current day Mexico.

The tour that day was much shorter than the previous day’s excursion so we found ourselves back in Trujillo where Francesca checked out a few museums. The Casa de la Emancipacion had an exhibition dedicated to the work of Maria Reiche who had charted and led the protection of the Nazca lines, and was a nice diversion for an hour or so.

She also checked out the Santa Maria Cathedral, which had really cool looking religious scenes but looked quite modern and snazzy, and also the main plaza, which was clean and spacious.

The next day, the 4th November, Francesca and I went to a couple of colonial house museums including the Casa Urquiaga (also the Central Bank) and the Casa Ganoza Chopitea, which had a restaurant inside.

The 16th century house we explored known as Casa Urquiaga used owned by a family of Spanish wealthy landowners, ranchers and merchants who had great political power in the city. Now the house is owned and maintained by the Central Bank, who allows visitors to see the exhibits.

Next we took a look at the beautifully painted Casa Ganoza Chopitea, and a few other painted colonial houses.

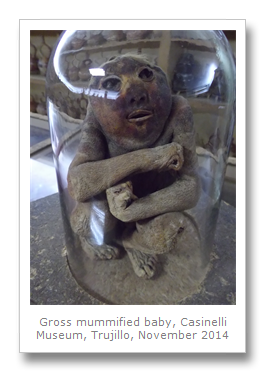

Francesca then checked out a private collection of Moche ceramics at the Cassinelli Museum. These pots and odds and ends were collected by a Mr. Cassinelli (since 1971) who made his money in fuel stations in Peru. Unfortunately he bought most of the collection from grave robbers, and has since passed away. The collection has apparently shrunk as his heirs sell off the pottery bit by bit, but it looks like it was worth a visit whilst you can still see them in a contextual place (Trujillo) all together.

The collection is not just Moche, but from many other cultures too, and even includes a mummified baby and musical conch shells, which Francesca got to play (even though they are centuries old!). The collection has started to be riddled with fakes according to some reviews too, so keep that in mind.

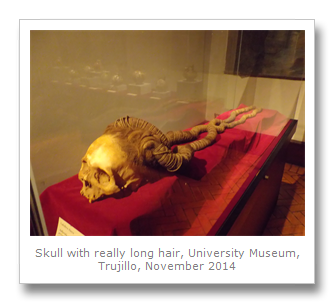

The Museo de Arqueologia de la Universidad Nacional de Trujillo had a good collection of pre-Hispanic ceramics too, and they told the story of the Moche through some well made dioramas or models made of clay.

The strangest objects here were mummified skulls with hair still attached that flowed back for several meters. Chimu mummies and colonial paintings make this a perfect museum to spend an hour or so in as well.

Trujillo was certainly one of the most interesting cities in Peru, with two different pre-Incan cultures to learn about, and plenty of colonial architecture to satisfy history buffs. Definitely a recommend, but forget about any kind of nightlife! Next stop: some Incan history at Cajamarca.

No comments:

Post a Comment