In Peru, much is said about the variety of climates and the geographical range, from the tropical rain forest, mountain rain forest, mountain grass scrubland, mountain alpine wastelands to the coastal desert regions. On the 20th November we took a bus across the whole range, from tropical Tarapoto, to coastal Chiclayo. Much of the journey meandered through rice paddies reminiscent of Asia, with the occasional flock of parrots flying around to a backdrop of ever increasing and colorful mineral-rich mountains.

On the 22nd November we went out into Chiclayo itself, located in the Lambayeque region about 13 miles from the Pacific. It was settled by the Spanish in the 16th Century and was named after the Cajamarcan word for the vegetable called squash.

We managed to find a hotel near a busy street but not too far from the center – Chiclayo does not provide much cheap accommodation outside the center, but it is considered a fairly unsafe city to travel through, and so the busy street was preferable, even if a little pricey.

The main square was pretty as the coastal sun shone down onto it, and we headed into the municipal palace building located at the square. The exhibitions there were very informative, particularly regarding the original civilizations of the region, including a description of the nearby Ventarrón temple, which was dated to around 2000 BCE.

A biography of archaeologist and ethnologist Hans Bruning was also on display. He was a German who immigrated to Peru around 1875 and became fascinated with the people and the pre-Hispanic culture there. He collected many important ceramics and other objects, took thousands of photographs of the indigenous people and there way of life, and also studied the Mochica language after winning the trust of a shy culture; eventually publishing the first Mochica dictionary in 1917. His wax cylinder recordings of Moche music are among the first recordings of popular music made in Peru. When his collection became too big for his house, he established a museum and sold the whole lot to the Peru government, becoming the curator and director in 1921. He died in 1928.

There were also some patriotic parts to the exhibit, with Chiclayo’s declaration of independence on display, and the dates it was elevated to a city including it’s coat of arms. Artwork from local students (possibly a competition) was also on display, with some actually showing some real promise. Someone had labeled the fire extinguisher, and I really could not work out if it was a joke or a piece of art – which could have been the intention, and shows the absurdity of modern art these days, that an every day object can be construed as a real at piece.

We decided to take a look at the Bruning Museum ourselves, and so we jumped in a transport van and headed out to Lambayeque, about an hours drive. The region was covered in litter, which is normal for South America, but this was a special kind of filth which some idiot had set fire to. Plumes of thick, acrid smoke filled the road for many minutes as we drove along, pouring torrents of potentially carcinogenic fumes into the air. Gross.

The Lambayeque Valley we were traveling through is comprised of numerous natural and man-made waterways which makes it ideal for agriculture, and the perfect spot for setting up a Bronze Age civilization or three. First it was the Moche culture, whose culture is dated from between 1 CE and 750 CE – they disappeared, probably due to deforestation and El Nino events causing such great climatic turbulence, that they abandoned their beliefs and traditions when they must have realized that their gods were not protecting them, no matter how many human sacrifices were made. The Moche then became the Chimu, who operated under a different hierarchical structure and who produced completely different styles of art. Their culture is dated as being from 850 CE until the Incans conquered them in 1470.

The controversy starts with the Sican culture, also called, confusingly, the Lambayeque culture, who overlapped the Chimu by existing between 750 CE to 1375, when it is supposed that the Chimu conquered their culture. There is no consensus as to whether these cultures really were that different, or whether they were all one, merely blending into each other. Naming cultures in Peru has been done by different archaeologists at different times, fairly arbitrarily it seems to me – the Moche are even referred to as the Early Chimu people by some historians. Throw the Wari and the Vicus peoples into the mix, and you have a confusing melting pot of cultures co-existing, influencing and probably waging war on each other.

At the museum we first encountered the story of Naylamp – a legendary warrior figure who first appeared on a flotilla of balsa rafts at the coast after the Moche culture had fallen. Naylamp apparently spearheaded his floating fleet from across the ocean, and came seeking to build an empire for himself. It has been asserted that Naylamp may have come from as far as Polynesia after particularly bad climatic catastrophes (probably caused by the same El Nino phenomena that did in the Moche), and, having found the coast abandoned, decided that this was a great place to settle his people.

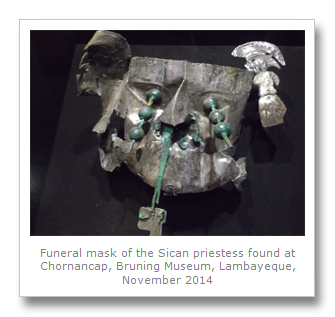

This story was passed down to us via the Spanish chronicles of Miguel de Balboa, who recounts that Naylamp settled twelve cities, one for each of his sons, all within the Lambayeque valley - when he died, he flew away to another world. This far-fetched tale remained pretty unbelievable until a new discovery in 2012 at the Chornancap temple, West of Lambayeque. There, tombs of seemingly elite rulers were found, and DNA tests have shown them to be completely different to the DNA taken from the contemporary Moche people, fueling speculation that this lineage was indeed the dynasty of Naylamp.

The remains found at Chornancap tombs were all female, leading to further speculation about the role that these women had. Were they priestesses, just like the Moche Lady of Cao is assumed to have been? Amidst all of these questions comes further craziness, in the form of wild theories (again apparently taken from Balboa) about how Naylamp founded the Sican culture in the Lambayeque valley, then continued East, leaving behind him evidence of an advanced culture. From the hydraulic irrigation systems around Cajamarca, to the bearded sarcophagi of the Chachapoyans, settling on the edge of the Amazon where he formed an egalitarian society in the jungle, no less.

Probably all nonsense, but we have asked around in all kinds of places, and full DNA testing has not been carried out on the people living in these places, and many tribes, particularly the Shuar and Kichwa people feel at best, uneasy, and at worst, defiled, at the thought of their DNA sitting in a lab somewhere. Until these kinds of medieval suspicions are resolved, we will likely never know the real ancestry of the disparate groups in South America. My guess is that the Naylamp legend refers to a true figure, who came from across the sea – possibly the Maya region (the Mayan culture also collapsed around the same time period). But who knows? Further investigation is required.

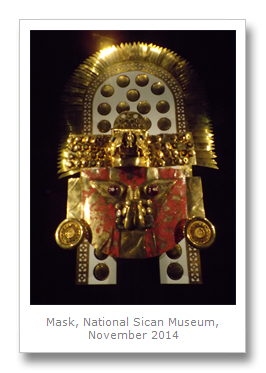

There were many other items related to the Chavin and Virus cultures, but by far the most interesting exhibits were related to the Sican culture, and the legend of Naylamp. A model of the Chotuna temple was on offer, with an explanation about how the region saw significant technological improvements in metallurgy and irrigation at the time of Naylamp. An architectural surge was also found, with numerous pyramids and settlements being built all around the region, from Poma in the Batan Grande region, to Tucume, which was built after Batan Grande was destroyed and abandoned, much like the Moche culture before it, due to adverse climate conditions.

There was a lot of information about the Chimu culture, whose black and polished ceramic pieces were so similar to the Sican pieces that have survived. The museums in this region probably could do with some better translations though, as they don’t really tell us a cogent story, especially if Spanish is not your first language. The Bruning Museums collection of metal objects really reflects the new expertise of the Sican people though, well laid out in their Gold Room (with about 500 pieces).

Our next visit was to the Royal Tombs of Sipan Museum (Museo de las Tumbes Reales de Sipan). This was also located in Lambayeque, a fairly easy walk from the Bruning Museum (bring a map). This museum was designed in the style of the Moche pyramids (including 3 levels, and access by a huge 75 meter long ramp), and the main purpose was to show off the findings of Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva and his wife Susanna Meneses. He had discovered the now famous Lord of Sipan pyramid (also called Huaca Rajada – confusingly located not in Lambayeque, but about 30km East of Chiclayo), which was constructed by the Moche around the 3rd Century, and was excavated in 1987.

The tomb had not been looted at all, which was unique in the 80s – an intact pre-Incan royal tomb. However, the discovery actually came about because police were tipped off that grave robbers were digging at the tombs – tipped off by other robbers who were angry they were not involved in the plan! Walter Alva was called in by police to help secure the area and make a speedy excavation to safeguard the integrity of the site. Apparently there was even a gunfight at the site, and cases against international smugglers were highlighted in the years to come by the FBI and Interpol.

There were over 400 precious gems buried with the Lord of Sipan (named after the village it was found near), and many more riches including necklaces, banners, shells and other adornments. The priests who were buried with the Lord all had had their feet removed, as had the warriors, said to be watching over and guarding the tomb.

Maybe proving that the Moche inherited their rulers, another tomb containing a direct ancestor of the Lord of Sipan was found in the same complex. His great great grandfather was buried with full pomp and splendor, along with two llamas, and three women (concubines?). DNA has proven the two Lords’ familial relationship, but not much else, and so the old man is now simply called the Old Lord of Sipan.

It was a buzz walking around a museum shaped like an ancient Moche pyramid with the actual findings laid out inside. You are not allowed to take photos inside these kinds of museums for security, as tomb raiders have turned their hands to flat out armed robberies in museums to get their hands on the gold and jewels.

Apparently Walter Alva is now planning on enhancing the existing museum by adding other Moche related goodies, including a botanic garden with all the food and medicinal plants that they used to grow being cultivated. Unfortunately, the sheer number of sites and the adobe material they are made from make them next to impossible to protect from grave robbers and El Nino events.

On the 23rd November, we headed out of Chiclayo, again by bus, to the nearby town of Tucume. The La Leche valley which holds Tucume, is the site of numerous archaeological finds – the largest concentration in Northern Peru, according to the local museums website. The Sican capital was moved here after the first one in Batan Grande was destroyed by fire. The region is located in a dry forest in a coastal desert area, and there we saw many different birds on the way in, including some very pretty Blue and Grey Tanagers.

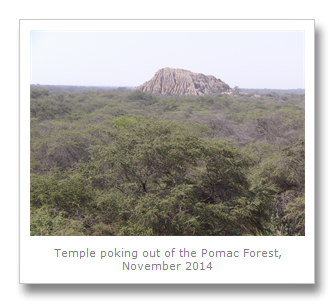

Looming up out of a sea of irrigated green fields is a site that locals now call Purgatorio, or Purgatory. At least 26 pyramids made of adobe are buried here, under a huge mound of sand and dirt. The region in totality may hold over 250 such structures, all decaying rapidly with erosion damage, and being destroyed by illegal digging. The area is now called Peru’s Valley of the Pyramids, rivaling those of Egypt, certainly in age at least.

The museum began with a history of the large hill sitting in the middle of the numerous temples: Stingray Hill. Stories passed down over the centuries tell of a lagoon that sat at the bottom of the hill – local people saw stingrays in it, presumably as it had been filled up by the sea. Over time people build their houses around the lagoon, ad the water eventually dried up – leaving just the name ‘stingray’ behind.

The surrounding temples are known as Pampa Grande (600 CE to 750 CE), Batan Grande (750 CE to 1150 CE) and Tucume (1100 CE to 1500 CE). The pyramids are now not all that impressive, as weathering, most recently in the El Nino events of 1982 and 1998, took it’s toll. The Batan Grande complex holds 34 pyramids, including royal tombs and the Temple of Gold – it was the one that the Sican destroyed by fire. After the Sican evidence has been found that the Chimu culture, and then even the Incans used the sites, as places of religious worship and perhaps even as a regional power center. The Chimu even painted large parts of the Tucume complex white, red and black which is the same color scheme that they used in their capital of Chan Chan in Trujillo.

In one structure, a huge storeroom was found containing lots of different treasures such as finely woven clothes. The Sican architecture was made using adobe and carob wood – with the walls tapering to a point at the top. It is thought that 2000 laborers would have taken up to one year to make enough bricks for one pyramid. Each brick was labeled with a different image or emblem to signify who it was that made it – presumably a way to record the labor effort of each worker.

The Tucume area was apparently largely ignored by historians until the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl became interested in it in the 1980’s. It was Heyerdahl himself who opened around 40 of the tombs found at the sites – including an Incan-era tomb where 19 women were found to have been buried with numerous textiles and weaving equipment. It is assumed these women were sacrificed.

The real treasures of course were jewels and precious metals such as gold. The Sican people’s mastery of smelting, molding and finishing metal works was a huge technological advance. Their ceramics were not bad either, and looking at the Sican stuff, you can see where the Chimu got their ideas from. Their colors were obtained from burning the pieces in closed ovens (black color) or open ovens (red color) – this is known because the technique is still used today by artisans of the region.

Another famous archaeologist worked on the Tucume site – Alfredo Narvaez. He discovered and uncovered a wall with adobe reliefs that portray birdmen sailing on rafts, which has been linked with the legend of Naylamp – whose name apparently means ‘bird from the water’. The figures on the wall both wear headdresses similar to those found on the royals in the tombs at Tucume.

Similar images on the reliefs found at Chan Chan are also present in Tucume – fishing and coastal animals portray heavily, especially Pelicans, Cormorants and even Catfish (found in the valley rivers). The museum at Tucume does a great job putting wall Sican iconography alongside ceramic objects that depict the same thing – whilst also illustrating with photos the actual object in question. Tortorro reed rafts are a great example – depicted on wall reliefs, in ceramics and by showing a photo of one.

There was a lot of good and interesting information in the Tumbes Museum, alongside some great and valuable pieces – particularly the curious miniature objects that were buried with people. It is supposed that many of the bodies found in the Temple of the Sacred Stone were sacrifices, or murders in modern speak - and that the victims were fed Nectandra, or Amala seeds before they died. These seeds were obtained through trade from where it natively grew in the Amazon region. They are hallucinogenic, and aided in the death of the victim. These sacrifices, it is supposed, were carried out to placate some long-forgotten god called Amaru (a serpent with wings and feline claws!).

The museum informed us that the Sican people were indeed great sailors, as their ceramics were even found in the Galapagos! Even if someone else took them there, there is certainly no question that they were great traders. They even traded with their future conquerors, the Chimu people. The highly skilled metal smiths were forcibly relocated to the Chimu capital, Chan Chan, when this happened in 1375.

Another mass burning of the Tucume structures occurred after the Incans had conquered the Chimu people – when Inca Atao Huallpa died and the empire descended into civil war just before the Spanish arrived. Regional instability occurred before the Incans could regain control.

Outside of the museum is a massive complex that surrounds the mountain centerpiece. We decided to take the short walk up to a relatively small collection of temples, including one called Huaca Las Balsas. No-one knows why these temples were built together, but the murals that were discovered were still in really good shape – very similar to ones we saw around Trujillo, and dated to before the Chimu period.

The dry forest area here was very pretty. Not much of it is left along the coast of Peru and Ecuador anymore, but this area is being preserved as part of a wider reserve surrounding Tucume called the National Sanctuary of the Pomac Forest. We did see some very colorful lizards and birds, including the Vermillion Flycatcher, the Peru Desert Tegu and the Anis, before entering one of the temples, where we also saw fox footprints.

The murals in the Huaca Las Balsas were very detailed and well preserved (the temple is named after the boats depicted on the reliefs). Navigation, sacrifice and rituals are all portrayed and well interpreted by the information boards (in English).

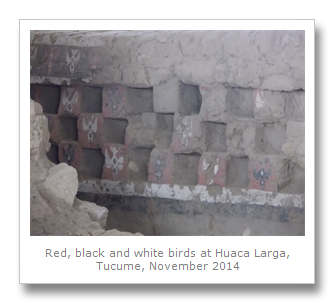

The rest of the site was a sprawl of various temples, in varying states of decay. Some of them were roped off, but we went in anyway, as no one was around to stop us. One walkway led down to the Temple of the Sacred Stone, where numerous artifacts have been unearthed. Another walkway led over the top of the mounds to the Long Temple, or Huaca Larga. This temple is the largest on the coast of Northern Peru, at 700 meters long and 280 meters wide. The Chimu and the Inca built on top of the existing Sican site, and we found some murals that had been uncovered with the painted birds still intact. Lovely!

It had been a long day, so we left to head back to Chiclayo. The next day, on the 24th November, we headed off again to a different part of Lambayeque region, to go and see the actual Moche site of the Lord of Sipan. There was another museum at the site, which had an excellent overview of Peruvian pre-Hispanic history, starting from the oldest official site, Caral.

There were so many temples in the area we could not really hope to see all of them, but the museum at Huaca Rajada, the Lord of Sipan tombs was one of the best, with a great museum. A lot of Moche art was on display from the multiple tomb that are at the site – still more being discovered today! The main three tombs, were the priest, the Lord of Span himself, and the Old Lord’s tomb.

When we visited the tombs themselves, we could see that the bodies had been replaced with the items found as they were excavated (probably all replicas), and there were many workmen shoring up the defenses against a possible El Nino threat early the next year. Peruvian budgets had allotted a small amount of money to protect these tombs – if it had been Machu Pichu, they would have thrown loads of money at it, of course, but as the infrastructure has not been developed in the North, the opportunity to sow off and protect these ancient sites has so far been missed.

Highlighting how poor the infrastructure is, we had to get a moto taxi from Sipan to the next archaeology site on our list, Ventarron. The poor kid driving the taxi had not a got a clue where it was, and got lost so we had to direct him from our poor knowledge of the area! It turned out to be better than his, though, and better than the state of his auto taxi, which suffered a blow out on the way. Luckily, some archaeologists we had spoken to were passing by, and they gave us a lift – we left the hapless taxi driver in the dust, with some money to affect a repair, and pay for the gas he had gotten on credit! No wonder there is no tourist dollars to transform these sites!

We arrived at Ventarron, which is ostensibly pretty similar to look at as the other sites we had seen in Northern Peru. Another reason for the sad lack of tourism. However, this site had something the others totally lacked – a great guide, who actually spoke English, and was passionate about showing us what he knew!

Our guide, Herbert, tagged along with us and gave us an excellent tour of the site. He is one of the archaeologists at Ventarron, and is passionate about what he describes as the site’s energy. Excavated first in 2007, Ventarron’s murals make them the oldest yet found in the Americas – around 4000 to 4500 years old. Scenes of deer hunting, geometric patterns and fishing were found on reliefs over three distinct phases. The temple was initially built around a rocky outcrop, but this rock was completely covered in the later phases as the temple was expanded.

Petroglyphs were also found higher up the nearby mountain, dated to about 4000 BCE, so obviously this site was being used by humans back to prehistoric times. It is now easy to see the insides of the oldest parts of the temple, and see how and where it was reconstructed as time went on. Evidence of Chimu and Incan building work can be seen when surveying the site from the entrance to the temple, high above on the mountain.

The mountain itself gave rise to the color scheme of the pyramid below. Blue, red and yellow minerals were extracted and used as bases for paints. Some of the murals had white circles on a red background – but the structure these were in, was destroyed by people using the sites as a quarry. Since discovery, the site has been robbed, vandalized and used as a dump, but the clean up and excavations goes on, and hopefully the site will get some protection at some point. We discovered, on this point, that there is a lot of competition between the archaeologists at the different sites. Rather than working together to uncover truths, it seems that political wrangling is the order of the day. From stealing each other’s research, to simply rubbishing each other’s ideas in a historic game of one-upmanship for personal or financial gain, archaeology seems to be more supposition than science – and any latent ideas of becoming an archaeologist I ever had were dashed at Ventarron.

Apparently, archaeologists from the oldest site in Peru, called Caral, which is located near Lima, came to Ventarron and were snide, negative and contrary, seemingly because they did not want to lose the ‘oldest site’ status, and all of the luxuries (money) that that affords. Ridiculous behavior which exposes a culture that negates thought and understanding and is totally unscientific, if true.

Our guide did tell us a few stories about the site, too. Some rocks were found at the back of the temple with polished holes in them. Not deep, but deep enough to collect water, it is supposed by Team Ventarron that these holes were used as collection points of rainwater, in an almost ritualized way to mark the circular flow of water and life. The water was collected, and used to water plants, which were then returned to the earth and dissipated in moisture only to rain down again. I think this is nonsense. We have seen these holes from pre-historic sites all across South America, with much better explanations proffered – example, they were holes in which paint was mixed, food was made, or even clothes were washed. This makes much more sense than the typical ‘ritual / religious’ explanations all too often given for seemingly simple pieces of evidence.

The other story was that of how the opossum stole fire, which was essentially a variation on a story that exists in varying forms from North America all the way down to Peru.

The people of Ventarron saw the fire on the distant mountain, and so they sent their best hunters to go and capture it. The fire kept moving to the next hill, time and time again, until the hunters were ready to give up and go back to the tribe empty handed. This meant shame, etc. They met the opossum who said he could get the fire for them, in exchange for food, and some alcohol they had. They agreed the terms, and the opossum took the alcohol and went away to get the fire. He came to a cave where a lone figure, the keeper of the fire was sitting guarding the fire. The guard roared at the opossum to leave, but the opossum managed to convince the guardian to drink some of his alcohol.

After getting the guardian drunk the opossum takes a coal from the fire, and puts it in his pouch (opossums are a South American marsupial). The guardian, of course, is no slouch, and proceeds to angrily beat the opossum badly. He even throws him in the fire where he burns all of the fur from his tail (opossums’ tails are hairless). The only thing that saves the opossum is when he plays dead, and the guardian throws him out of the cave. The small mammal makes his way back to the tribe, where he gives them the coal, and they now have fire – where the opossum dies. The legend was passed down, and the opossum became legendary. That is the part of the story where our guide showed us an adobe relief of an opossum which sat next to a hole in which fire debris was found.

Nice story, and well told by the guide. Ventarron is a lovely and interesting site, and well recommended by anyone with even a passing interest in archaeology. The infrastructure was as poor as ever of course, and it was one of the workers who gave us and the guide a lift back to the bus stop to get back into town – so it won’t be everyone’s cup of tea.

The next day, the 25th November, we continued out archaeological tour of Lambayeque by heading back out Northwards, but this time to another town called Ferrenafe. Here we found another regional museum called the National Sican Museum, which is dedicated to the Sican culture itself. A Japanese team helped set this museum up, and it is highly recommended as the foremost authority on the evidence found, particularly in the Leche valley, around the Batan Grande sites.

One of the most interesting discoveries at these temples were the graves of people who were tied to stakes made of carob tree. These stakes were found to be demarcations of corners, walls or other important areas in the pyramids, but the gruesome discovery of people tied to the bottom of the columns, and presumably buried alive must have been quite a shock!

As with most other South American museums, this one had no information in English, whatever, so go informed! The most interesting stuff was about the different temples at Poma in Batan Grande, probably because Ferrenafe is the gateway to the Pomac Forest, which is where all of the pyramids are located. The Parrot Temple’s Eastern tomb had the most evidence of funeral practices, including one body found upside down in the dirt in the seated position.

Explanations of the metallurgic processes were displayed, and the models of the tombs, including the reliefs found were very vivid and stirred the imagination.

After the museum we managed to get a bus to the Forest itself, which is home to several pyramids and archaeological sites, and also over a hundred bird species. We walked from the entrance in lieu of having a car, down to a large algarrobo or carob tree, which is supposedly over 500 years old.

We did see some birds flying around, but then we were lucky enough to be able to flag a taxi down and negotiate with the driver to take us around the forest. This was a good idea, as it got extremely hot very quickly and we would not have made it very far.

Our first stop, as we passed the dry Lercanlech river was the Huaca las Ventanas (Windows Temple) which featured heavily in the museum. This site was where they had found a beautiful gold knife, and from the top of which you can see for miles around, with temple after temple sticking out of the surrounding dry and thorny forest.

It was a short walk to the Gold Temple from here, where we found some remains of a mural with colors still on it, just lying around. Clearly these sites should be protected a bit better, and more work needs to be done to reconstruct them all and protect them from the extreme weather conditions.

We saw a lovely Burrowing Owl sitting by it’s hole in the ground. These little critters live from Canada down to Tierra del Fuego, and have extremely bright yellow eyes. A truly beautiful bird. We also saw some very small Pacific Parrotlets sitting in the trees. They are tiny, lime green with a streak of blue by the eyes. Apparently they are worth up to $200 each, but I think they are priceless when they are free.

Our last stop was the Huaca la Merced, or Mercy Temple. Up here we saw lots of Turkey Vultures flying around, with more great views over the forest. It was good to see some of the workers putting up some El Nino defenses, but it is not a surprise that we did not see any other tourist on the entirety of our trip in Chiclayo – the ruins are mostly just large mounds of dirt, with not much reconstruction having yet taken place, and explanations solely in Spanish, and infrastructure non-existent. Still, it was worth it, especially to see them now before we lose even more of them to erosion and human encroachment.

We trekked a little through the forest before we met up with our taxi driver. We saw some lizards but not many birds. We finally made our way back, by bus to Ferrenafe, then changed and got a combi shared taxi van back to Chicalyo. I took a long but damning video of the way Peruvians treat their own environment, with burning litter strewn all about the streets outside their own homes. Disgusting.

The next day Francesca went to the famous Chotuna Chornancap site where the legend of Naylamp was supposedly given credence. The reliefs at this site were very much like the Chimu decorations at Chan Chan, but archaeologists assert the temple is Sican. Underwater tombs were found here, along with a burial site of 33 women who were murdered. This is the site most associated with Naylamp, yet his whereabouts are conspicuously missing, although sources say the DNA of the bodies found were not contemporary to the region. This site is one most at threat from climatic conditions, and money is so tight, archaeologists have now resorted to crowd sourcing to fund protection and further excavations.

Many of the digs have to also pay the local people off, ostensibly because the people own the land, although most of them are illegally settled. Really, I think it is a payment to stop them looting the sites. Persuading the people that tourism is coming and will be a good thing if they stop illegal digging seems to be benefitting the local populations. Ventarron is a good example of a project that bought electricity and clean water to the locals, but at what cost when they do not do these things for themselves?

A quick picture of the longest balcony in Peru (found on a colonial house in Lambayeque), and Francesca headed back to Chiclayo.

This region, underdeveloped and dirty as it is has some fabulous offerings if you are willing to put some effort into getting around on the public transport – the iPeru tourist information office has some excellent maps, and advice, which is rare in this part of the world. Next time, we will rent a car.

No comments:

Post a Comment