After pulling our bus over and boarding it like mad banditos in the middle of the Argentine desert, we made our way across Mendoza province South to Neuquén province. The vast flatness of this central desert marked the beginning of our trip into Patagonia. We had organized a couchsurf in Neuquén and waited in the new bus station for Margarita who picked us up at 8am after the overnight journey. Margarita was a language teacher who taught Spanish and English at school, and was also a pottery artist. Once we arrived at her home, she generously made us some breakfast and after chatting, Francesca and I had a nap to catch up on sleep.

We got up later that day on the 13th November, and all three of us decided to head out to one of the main tourist attractions in the area – a place called Villa El Chocón. Margarita drove us down in her car, and it took about an hour and a half to get there – she had been before but really enjoyed the history of the place.

Villa El Chocón is one of three main places around Neuquén province that tourists visit for everything dinosaur related. El Chocón has the Ernesto Bachmann Paleontological Museum which holds some of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs, and on the shore of the river Limay (now a reservoir used for irrigation and hydroelectricity generation) there are sets of several different dinosaur tracks which are viewable from constructed viewing platforms above them. The other two tourist sites are Plaza Huincul (the Carmen Funes Museum holds the largest dinosaur remains that we have), and Rincon de los Sauces (the Museo Argentino Urquiza holds some of the oldest dinosaur eggs ever found).

It was a beautiful day and we stopped off at the reservoir first to see the views from the mirador. The water looked warm and inviting but we knew that they would be pretty cold this time of year. The dam had created such a large lake that there were now islands in it. Margarita told us that locals come here and sunbathe like it is the beach! There were models and pictures of dinosaurs all over the place too, and, as no-one was really around, it was easy to imagine dinosaurs living here all those millions of years ago.

We made our way to the Ernesto Bachmann Paleontological Museum which was pretty easy to find (it was inaugurated in 1997 as the Museo Municipal De Villa El Chocón). This was one of the best and most put together museums we had seen in South America so far, and it started as it meant to go on with a huge room containing the almost complete fossilized skeleton of Giganotosaurus carolinii – found 18km South of the town. It is billed here as the biggest carnivorous dinosaur ever to have existed - definitely as big or bigger than Tyrannosaurus rex (‘terrible lizard’), but research online showed us that Carcharodontosaurus (‘jagged toothed lizard’) and Spinosaurus (‘spined lizard’), both found in Africa, were bigger.

Discovered in 1993 by Rubén Dario Carolini; a rancher with a keen interest in dinosaurs – this find made us wonder how many other ranchers, construction workers and oil prospectors simply destroy or throw away their dinosaur fossils because it is more economical or easy to do so than to contact a museum. This Giganotosaurus (‘giant Southerly lizard’) was an 80% complete skeleton and lived at a time when dinosaurs were extremely big in the Late Cretaceous (100 million to 65 million years ago). Fossils of related species have led to speculation that these animals hunted as packs and therefore could have bought down the huge herbivorous dinosaurs that lived at the same time. Speeds of up to 30 miles per hour (50 kilometers per hour) have been calculated for these killers. They were actually a similar size to the more famous Tyrannosaurus rex but hunted in different ways. T-rex had a powerful bite and it is reckoned that it killed like a jaguar or puma by using forceful bites to crush skulls or necks, whereas Giganotosaurus used it’s razor teeth to slash prey and bleed them out.

I found it really interesting to learn that dinosaurs are classified into two main groups according to the position of the pelvis – saurischians have reptilian positioning of the pelvis, whereas ornitischians have bird-like positioning. This is just an evolutionary convergence, and it is the saurischians group that most famous dinosaurs belong to. They are broken down into two more distinct groups – sauropods, or big herbivores with long tails and necks, and theropods – carnivorous bipeds.

Dinosaurs originated in the Triassic period 230 million years ago, before becoming extinct 65 million years ago. They differ from present day reptiles in the positioning of their extremities – current reptiles legs lie horizontal and stick out from their bodies whereas dinosaurs are columnar or vertical.

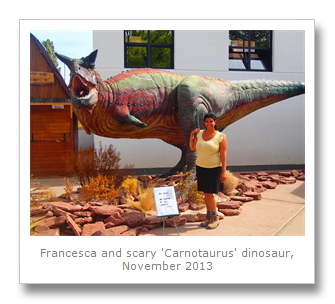

The museum had wonderful examples of other theropods such as the Abelisaurids, including Carnotaurus sastrei (‘carnivorous bull’), which was one of the most well-preserved skeletons ever found, including skin impressions and colors. This dinosaur had the classic short snout, and small forearms of the theropod which caused it to be mistaken for the Tyrannosaurs – but it also has two horns on it’s forehead hence it’s name. All of the dinosaurs were found in central and southern Argentina relatively close to where the museum is located (this area was the Western edge of Gondwana – the Southern part of the super-continent Pangea which broke up in the middle of the age of the dinosaurs).

The museum also had on display some of the later, but smaller, sauropods – the herbivorous long-necked dinosaurs. Neuquensaurus australis was around 6 meters in length, much smaller than earlier primitive titanosaurs, and had evolved to be more armor-plated with bony nodules protruding from its thick flesh which were also found on later reptiles such as crocodiles and even mammals such as the glyptodon and armadillo.

There was some really interesting contextual information in this museum which explained the different eras, eons and periods and when the different dinosaurs existed within them. They even had explanations for the different types of fossils and how they are formed.

Paleontology comes from the Greek words meaning ‘study of organisms from the past’. Physical evidence of these organisms comes in the form of fossils.

There are four types of fossilization:

1. Permineralization: minerals are carried within water to fill the cells of dead organisms. The deposited minerals form a kind of crystal cast of the organic structures. This is the most common kind of fossil and made up most of the fossils in the museum.

2. Carbonization: the pressure of fine grain sediments on the dead organism (usually leaves and small animals) forces the organism to expel liquids leaving behind a carbon film which reproduces the shape of the organism.

3. Mummification: usually soft tissue is only preserved in ice or amber where no oxygen can degrade the cells completely.

4. Imprints/Molds: no remains are preserved, only the space in the sediment where the organism was is preserved. Usually fossils of this type are shelled invertebrates (molds) or leaves (imprints).

Of the three types of rocks, only sedimentary and metamorphic rocks can hold fossils, with sedimentary rocks yielding the most which is why paleontologists favor these as their stomping grounds. Sedimentary rocks are existing rocks that are layered (usually transported by water, wind, glaciers or waves) on top of other rocks. When these layers are eroded again, they are exposed with any fossils that have been created. Metamorphic rocks are formed by the modification of rocks suffering high temperatures and pressures, usually at great depth and so do not normally have fossils. Igneous rocks like basalt or granite are formed when liquid magma is cooled in the Earth’s crust and mantle. The rocks covering them are eroded, exposing them, and, by their nature, they never hold fossils.

The last few sections of the museum were pretty cool on their own – insects from millions of years ago on display in the amber they fossilized in, shells and leaves molds and imprints too.

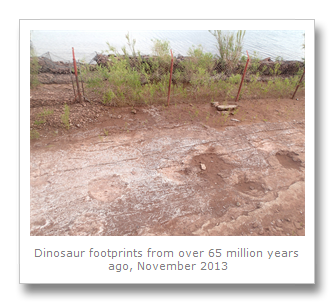

We left with a much better understanding of dinosaurs than ever, and went exploring for the famous footprints of El Chocón. These were a bit more tricky to find, but eventually we found our way and drove down to where a small camping ground and lodge were located next to the reservoir. Fishermen were dipping their lines in the freezing cold water, but not many people were about. We were the only tourists there looking at these footprints from millions of years ago.

The authorities have now seen fit to erect a fence around the footprints, and also a flood barrier. A metal walkway has also been erected above the prints, so now you can view them from above clearly, without any threat to the prints themselves.

You can clearly see the three-toed prints of a theropod and two sets of sauropod dinosaurs (one small one, one much larger) walking side by side. It looks like the theropod may have been hunting the two sauropods but it is not really possible to tell. The footprints go across the reservoir and can be seen in two different places – unfortunately, due to the water being really high and covering one of the sites, we could only see one – but it was the main one. It was awesome to see these so close and see the sheer size of the stride of these awesome beasts.

We all decided to make our way back to the house which was in a district just outside of Neuquén and so Margarita drove us back. On the way back we had to avoid some crazy Argentine drivers – the driving standards in South America can be extremely poor all too regularly.

We all shared a lovely home-cooked meal that night, and we decided to share our wine we had bought in Mendoza with our generous host – and it was just as nice as when we taste-tested it at the winery.

The next day we were cut short going anywhere because the wind picked up and was blowing so strong they had to cancel the interstate buses. We decided to spend the day relaxing and catching up with some blogging and so we stayed in. The next day was much better, but we had found out that one of the places we wanted to visit had been closed due to a lack of funding. Proyecto Dino at Lago Barreales Paleontological Center (a few hours by bus from Neuquén) had not been replying to any of my emails, although their Facebook page still looked active. Margarita knew someone who worked there though, and we eventually found out it was closed indefinitely which is a shame because it is one of the only places in the world where you can help on a paleontological dinosaur dig. Gutted – was really looking forward to fulfilling a childhood dream – so close, too – it had only been cancelled a few months before…oh well.

The day before we left Neuquén (the 15th November) I went for a walk along the river North of the house, the Rio Negro. In fact, the other side of the river was the province of Rio Negro. Along the way I was scared shitless by two huge dogs that appeared from nowhere, but luckily paid me no attention. I did see red-crested cardinals, a dead fox, some beautiful river views and some drunken guys set a fire and send it down the river like a miniature Viking funeral.

We decided to see the Plaza Huincul museum, the Carmen Funes Museo, the next day after leaving Neuquén on our way to the next destination. We had checked and double-checked opening times and bus schedules and got the bus there in the morning after Margarita kindly dropped us off as she had picked us up at the bus terminal.

We asked the conductor on the bus to drop us off at the museum which is at the start of town on the Eastern edge. People gawped at us and the museum as we exited the bus like they had only just noticed it was there, and we crossed the road only to find it was closed! What the hell?

We soon realized it was the weekend, though, and it would open in one hour. However, one of the museum’s staff saw us outside waiting and told us we could come in early which was nice of them.

This museum was split into two sections, the first part which was dedicated to the founding of the town and the national oil company YPF’s role in doing so. YPF had buildings here since 1921 (oil was discovered 3 years earlier), but the town was founded in 1966, and has been producing oil ever since.

The museum’s namesake, Carmen Funes, was a barmaid who served soldiers in the desert campaigns against Chile who then settled the area and gave respite to travelers at her ranch.

There was also a little information on the Mapuche tribe who lived in Patagonia, including some weavings that they are famous for. The Mapuches were considered a hard core warrior race who never conceded defeat to the Spanish and they proudly live, to this day, as Argentinians or Chileans.

The main attraction was in the far end of the museum, a huge room filled with dinosaur fossils and models. All dinosaurs you see today are casts made from dinosaur bones and wired together, and this room needed to be big to house one of the largest dinosaurs ever to have been found: Argentinosaurus huinculensis. This huge beast existed 97 million years ago, and it’s length has been estimated up to 35 meters from nose to tail making it one of the biggest creatures ever to have lived. Being between 80 and 100 tones, this dinosaur was almost certainly too big to have had any predators in adulthood, even though it could only move extremely slowly due to its enormity.

Only a few bones of the Argentinosaurus have been found, but they used other more complete titanosaurs to build the models which now exist around the world. It was two paleontologists; Jose Bonaparte and Rodolfo Coria (the first director of the museum) who discovered this particular type of Argentinosaurus, around 8km from the town. Argentina’s famous bravado and overstatements were on display here again when they claim that this is the biggest dinosaur in the world ever to have been found – but, again, research shows Amphicoelias, found in the US, is now thought to be the biggest dinosaur ever to have been discovered.

Whatever the biggest creature actually is, it is no less impressive to stand underneath the 35 meter long model of this behemoth and wonder how they would have regarded us. The strange spines on it’s neck, it’s hoof like foot with finger bones, and the length of it’s counter balancing tail were amazing.

There were also bird and dinosaur footprints on display, a fossilized ichthyosaur (a marine dinosaur which is basically a cross between a crocodile and a shark), a model of Giganotosaurus and some smaller dinosaurs.

Anabisetia and Gasparinisaura were both small herbivores, bipedal and around 2 meters long. It is estimated that they were very agile and fast. The scariest looking dinosaurs, however, were the Unenlagias and the Patagonykus. The former means, ‘half-bird’ due to it’s reptilian body and legs, and wing-like forearms. The latter was a two meter long theropod with strange claw-like bony forearms. There is controversy about these dinosaurs, as only incomplete skeletons have been found – but the models which are based on current best guesses are pretty terrifying. Monsters really did exist!

This area is a must see for anyone backpacking through Argentina with even a nascent interest in science – we really began to admire how many diverse activities there are in Argentina. Not surprising for a country that is the 8th largest in the world.

We left Plaza Huincul and made our way back across the plains of central Argentina East towards the mountains again. Francesca will tell you about our stay in the lazy village of Junin de los Andes.

What species of dinosaur was the big femur you stood next to?

ReplyDeleteHi Nima, I thought it was the Argentinosaurus but those bones were at a different museum in Patagonia to the one were the photo was taken. I am not actually sure what species the dino bone was from, only that it was a Titanosaur. I will look at some of our other pics an see if I can find an answer for you.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your visit, guys!

ReplyDelete