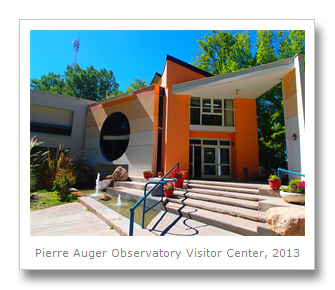

We said goodbye to Juan and his friends leaving Mendoza on Saturday afternoon (the 9th of November) to head on to Malargue. While it wasn’t ski season when we were in Malargue (Las Lenas ski resort is famous and near the city) there were still plenty of reasons to visit this expansive pampas region. I had been communicating with a woman working at the Pierre Auger Cosmic Ray Observatory about visiting the site and learning more about the project which had an international community of scientists studying ultra-high energy cosmic rays, which are the most energetic and rarest of particles in the universe.

Arriving in Malargue, we had a quick chat with the information lady before making our way into town to find a hostel for a few nights. The hostels listed on Booking.com were all very expensive, so we decided to chance it and arrive without a reservation. One of the first places we came across was a pink hotel called ‘Bambi’ where the owner offered us a deal – $320 pesos/night if we stayed 2 nights. This was still a bit pricey, so we thanked him and kept walking around until we eventually came to an Hosteling International in the center of Malargue that had plenty of rooms free. They didn’t have any of the HI discount card left available (we didn’t have one) but allowed us to stay at the discount rate anyways. At $210 pesos/night this was a much better deal! It pays to shop around. Plus that evening the owner made us a delicious pizza, one of the best we had in all of Argentina! (Make sure to order one if you stay there.)

Colin and I spent the rest of the evening, and all of the next day (November 10th) catching up with some admin work (yes, when you travel for this long, you end up with plenty of admin!) and resting. Our visit to the observatory was set for the morning of November 11th. The week we were in Marlargue happened to be the week of the 33rd International Cosmic Ray Conference, a meeting of scientists from around the world which occurs twice a year. We really lucked out – the scientists we were going to speak with, Antonio Bueno and Bruno Zamorano, were only in the area from Spain for the conference.

We sat down with the scientists Antonio and Bruno and started by asking the basics – what exactly did the Pierre Auger Observatory do? We knew it used strange-looking plastic ‘bubbles’ (or so they appeared to me) to detect microscopic particles coming to earth from outer space, but what were these particles? Turns out, the scientists didn’t know either – that was the question their work in the observatory was trying to answer. What exactly are the ultra-high energy cosmic rays their devices kept detecting and where were they coming from? Their best guess was that these cosmic rays are sub-atomic particles which are likely protons or neutrons. These particles come to Earth from outer space, traveling at the speed of light. When these particles enter and interact with the Earth’s atmosphere a measureable reaction occurs. The amount of energy released by these high-energy microscopic particles is equivalent to the energy of a thrown tennis ball.

The scientists walked us over to a small model of one of the detectors they use to detect and record such reactions. They looked like light-colored plastic ‘bubbles’ from the outside, with a vinyl inside which is filled with clean water. Inside the ‘bubble’ are shiny silver photomultipliers which work similar to digital cameras, except they are activated to ‘record data’ when an energy particle is detected and a light flashes. The more energy from the particle, the larger the flash of light is – and by detecting the frequency and intensity of the light, the scientists can understand the intensity of the particle. Sometimes when there is a “shower” of particles near one of the detectors the photomultipliers become so saturated with data that they becomes useless – akin to taking a photograph with the sun in the background.

This international project chose the pampas region in Argentina due to its dry and calm weather and its huge areas of flat land with no streetlights, which are necessary to ensure accuracy for the detectors. The detectors are very sensitive, they told us, if an animal interferes with them or there is bad weather, they might be activated inadvertently. The project spent $50 million to install thousands of detectors over a 3,000 km2 area of the pampas – we recognized the devices as soon as we saw them as we had seen tons from the bus window on the way to Marlargue. The scientists explained they needed so many detectors because the high-energy particles they are trying to understand are very infrequent arriving just 1 per km2 per century – covering the maximum amount of ground is pretty much mandatory. In fact, their work would be more precise if they had even more space, but this would require more funding on a project with a pretty slim budget.

OK. So we understood just how difficult these particles were to detect, but – how were they discovered in the first place, without thousands of detectors? The scientists told us a story:

In 1912, a scientist named Victor Hess took a hot air balloon 5000 meters up in the air in order to prove his own hypothesis that the radiation detected by many at the time was from the earth. If this were the case, the level of radiation detected should decrease as the altitude one took a measurement from increased. However the exact opposite proved true. As Hess took measurements in various altitudes from his hot air balloon he uncovered that the radiation detected increased when the altitude increased. In fact, the radiation detected at 5 km was twice the level detected at sea level. These findings led Hess to realize the particles weren’t coming from the Earth – they must have been coming from outer space! This conclusion earned Hess the 1936 Nobel Prize.

And thus support for discovering the nature of these ‘cosmic rays’ from outer space was born and detectors were eventually produced. While $50 million may seem like a costly investment from the international community (it isn’t that much, when considering other scientific projects) the detectors are useful for more than just detecting high-energy particles, and thus the investment goes a bit further. The scientists informed us that the project gives them very good data on the atmosphere and helps monitor the weather. That’s a good thing, because unless the current cosmic ray project gets more detectors (and more financing) there isn’t much chance they will find the answers to the larger questions of what the particles are and where they come from! While the detectors give the scientists plenty of data, the two we spoke with compared deciphering this data with Gregor Mendle drawing information by looking at the peas before the pigeons.

There is some hope for more information however. The scientists told us there are different types of detectors at another project based in Utah which are an improvement on the design at the site in Argentina. Also, Japan is developing a detector which will work in outer space.

After our chat was finished, we thanked the scientists and headed outside. On the way we saw some beautiful and colorful flowers.

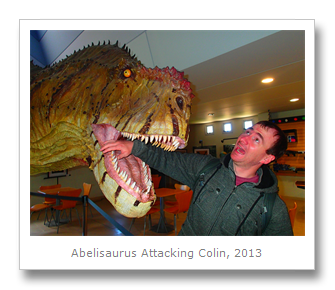

After a stop for some pasta lunch we decided to pay a visit to a really cool-looking planetarium. This planetarium had all kinds of little games you could play and interactive exhibits such as the ‘human battery’ game where we put our hands on a copper plate and a zinc plate in order to gauge the electrical charge in our bodies. The dial did move! There were also a few different sundials which displayed the time via shadows.

The place wasn’t very big, but we had fun walking around it. One finished we took a walk and got some photos of the Andes in the background and some interesting nature.

Later on we decided to go to the reach out program for the public at the Cosmic Ray conference, which discussed some of the science festivals and events about physics from around the world. I’ll tell you about the next part of Malargue in a separate post – volcanoes!

Francesca

![Tel&Obs_PierreAuger_website_croppedNov2011--rgov-800width[5] Tel&Obs_PierreAuger_website_croppedNov2011--rgov-800width[5]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiGiE1pTsbFrdoHaU73jX0cDey1D4LoCF-dZP6AK1ML0Kh1sxdXjBAIJdVtSoMnTAYXK9YwIdIa8Ad_i7Fkml9UddlVBObQG90zBYqOU4yo6r8Mflp7-09PFtXm8E8f3MvpEh_JYSbxfEI/?imgmax=800)

No comments:

Post a Comment