We arrived by boat to Argentina on the 19th July, crossing the Rio Uruguay by passenger ferry in the afternoon. We had been stamped out of Uruguay by an unconcerned official, and we were seen off by the perpetually annoying stray dogs that were simply everywhere you turned in Uruguay. A 40 minute boat trip bought us to Concordia in Argentina; me for the second time after our visit to Iguazu Falls, and Francesca, for her third visit after she visited the Jesuit mission in the Northern state of Missiones.

It felt good to be making progress on our journey and reaching our third country on our South America trip. It was a good crossing, with not much to see, and the ferry was packed with convivial dollar tourists who had popped over the border to obtain much needed dollars from Uruguay. Taking a look Argentina’s economic history shows us why this is now a popular trip for many people to take.

There are a lot of periods of strife and political turmoil in Argentina’s brief history. A promising start at the end of the 19th century, after the economy entered the world stage through livestock and grain exports, was compacted by a huge growth to population ratio in the period following WWII. The country was even the sixth richest country in the world. This was bought to a crashing halt with a (all too familiar for South America) dictatorship period from 1976, in which the chief economic policies were disorganization, corruption and financial liberalism. This left over 400,000 companies bankrupt, countrywide by the end of 1982. Even earlier than this, Juan Peron had introduced terrible inflation with his and his wife’s (Evita) socialist strategies and nationalism.

By 2002 there had been widespread rioting due to inflation, unemployment (25%) and the devalued peso. In fact, it seems Argentina lurches from one financial crisis to another. At the end of December 2001, the government froze a large number of the people’s deposits after a huge run on the banks, they defaulted on their loans from the IMF, and the GDP had shrunk 20% in just 4 years. Finally, after 5 different presidents in less than two weeks (it would be funny if it was not so dangerous), Minister of the Economy Roberto Lavagna rescued the country from going down the toilet completely after stabilizing prices and the exchange rate.

Since the late 20th Century, agriculture and particularly the export of soya has become a base of Argentina’s GDP. This coincided with Nestor Kirchner’s presidency. Nestor was the husband of current president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. Since she came to power, President de Kirchner’s government has re-nationalized various sectors, including the private pension funds; sold a large portion of the IMF debt to Venezuela; attempted to increase taxes on soy bean exportation (and failed) and made it illegal for anyone to trade in the dollar. Due to inflation being so high, and confidence so low, the government have essentially resorted to a siege economy, trying to maintain the number of dollars they have so they can pay their debts and to keep the peso from being devalued further. This has resulted in a stabilization of reserves at the Central Bank, but as with all things in South America, unwanted side effects have surfaced. Namely the burgeoning unofficial market, where people sell their unwanted pesos for almost twice the official rate, so that they can get their hands on US dollars which they use for savings and trade. There is so little confidence in the peso, in fact, that people have been known to even offload them for bitcoins these days.

To benefit from this situation, we had been stocking up on US dollars for weeks before arriving. The idea is, rather than get pesos out at the ATM for an exchange rate of approximately 5 pesos per dollar, we change dollars on the ‘blue market’ for about 8.4 pesos per dollar. Usually the people you exchange the dollars with feel they are being done a favor as they can save the dollars and avoid being adversely affected by inflation and the devalued peso. We did read, however, that sometimes these deals can go bad. An American in Buenos Aires followed a money changer into a building to make one such illegal transaction, and on his way out he was shot in the leg and robbed. We would have to be careful.

Our first stop would be to try and find a money changer, also called arbolitos, or little trees due to the little ‘green leaves’, or dollars, they carry. Our taxi driver took us (and a really stinky other couple), to Concordia’s city center. We had already agreed a price Uruguayan pesos, so we unloaded our last Uruguayan money to the taxi driver as he sprayed his car with air freshener, and carried the bag over to the money changer. Francesca had found he address of one whilst we were waiting for the ferry. In fact, we went to casa Julio, but found a better rate across the road in a money changer, disguised as a gold exchange. They call these cambios.

I left the bags with Francesca outside, a little way down the busy road, and bought $US100 in with me. I asked the guy in broken Spanish how many pesos for the dollar, and he told me 8. According to research already done, this was the going rate so I handed over my dollars as he gave me a fistful of pesos. I recounted them, thanked him and left. No problems! In fact we changed here again a few days later again with no problems whatsoever. Our hundred bucks got us 800 pesos, where as if we had made that transaction at the ATM, we would have gotten about 540 pesos only. Illegal, remember, but very tolerated. The law does not seem to be enforced at all.

We humped our way across a main plaza, with the directions from a couple of very helpful ad friendly cops, and entered the tourist information point. They gave us some information about a hotel we could check into only a few blocks away, and the national park we wanted to see.

Hotel Florida was a nice find. We checked in, and it was an inexpensive place to stay. We had to get used to the new currency, and the new way of only spending cash, rather than using the credit card which would be at the official exchange rate, losing us money.

We settled our stuff in, and set out across town to look at some shops and get some food. The story of siesta in South America is not a myth – literally all of the streets that had been so packed and teeming with people an hour or two before were all deserted. Everywhere closes between about 1pm and 4pm, depending on the day and the person working. Even street carts were left where they were standing with all of the produce still on it, and no-one to be seen!

We eventually found a buffet place open, which had a massive selection of food. It was not cheap, but we felt like a treat, so stocked up on everything from pizzas, to meat and deserts.

Feeling full, we jumped into a taxi to the local park (Parque San Carlos) where we had heard there was a castle that had inspired the story The Little Prince. Actually, the author, Antoine Saint-Exupery, used to fly airmail routes in Argentina, and one time his plane came down (technical problems) in a field which is now the park. A French family lived in the San Carlos castle at the time, and he made new friends, visiting there many times. This was many years before he flew planes in WWII, where he disappeared whilst flying near France in 1944, apparently shot down by the Luftwaffe. There is a statue outside the now ruined San Carlos castle of The Little Prince on his asteroid.

The park is quite large, so we decided to have a nice long walk around it. From the highest vantage point, we could see the Uruguay river – and on the furthest bank, Uruguay itself.

Nearby, was a monument to the Oriental exodus, which was not an immigration push to get more Chinese to Argentina, but was the result of the move made by General Artigas (the father of Uruguay) when he split away from the revolutionary group called Banda Oriental. His supporters followed him from Uruguay to Entre Rios (the state we were now in), and this exodus of Artigas and his people led to the formation of the League of the Free Peoples, with which he liberated Montevideo from the Unitarians of Buenos Aires.

This is a monument which you would expect in Uruguay, not Argentina, but there seems to be a huge kinship of peoples around South American borders. Many local people do not seem to really be all that bothered about borders. Culture, customs, and language all become blurred between one country and the next around the border regions. We had heard that people from Argentina’s capital are extremely arrogant, and when they go to Uruguay they treat their neighbors with scorn. This is not true for the poorer and simpler folk from these border regions however. They, like the Uruguayans are steeped in the same gaucho culture and rural customs of the region. They are also extremely friendly, and hospitable.

Francesca collected some extremely bizarre rocks from the park too. Some were green, some yellow and some red. One was glassy, and looked like an animal kidney, and one had strange lines inside it. Some were jagged, and sharp, others, smooth, like eggs.

As it was getting dark, we decided o make the walk back. We were going to get a taxi, but the sunset was beautiful, so we walked the 5km back in about one hour.

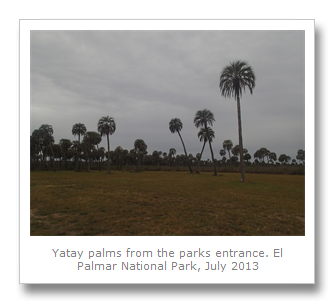

The next day we got up early and had our hearty breakfast at the hotel, loaded up on water, Oreo cookies and some fruit, and headed to the bus station. We got the next bus which was leaving in 5 minutes that would drop us off at the Parque Nacional El Palmar. This National Park is home to a huge forest of endangered Butia Yatay palms. At 85km squared, it is a large park, and we had researched it pretty decently and found that they had English speaking guides who would escort you. We had reasoned that if a car was needed, we could probably get them to call a taxi or give us a lift themselves. No such luck. There were no English speakers there. Only Spanish guides who told us we would have to walk the 12km to the end of the road, where the forest meets the river. We feared another Monte de Ombues moment, but soon took the attitude that we had all day and would just see as much as we could. We intrepidly paid our entrance fee and started the walk up the road. The weather was overcast with a slight chill in the air, so we preyed it would not rain. After about half an hour, we realized it would be a large undertaking to make the walk round the three different routes you can take, because of the distances.

Luckily for us we were on foot when we saw, in the distance, a startled herd of marsh deer. They moved across the road in front of us, too far and too fast to get a good photo, although we did get a snap of their tracks once we reached their crossing point.

Not long after this, we got a lift to the entrance of the first circuit route leading from the main road by one of the guys who lives (and presumably works) at the park. That saved us a walk of about 4km, and so we headed down the first route, which was a walk of about 3km itself! The road soon split into two, with a sign indicating that cars should drive around in an anti-clockwise direction. We duly followed the track, and soon the sparse yatay palms that we could see all around us became more bunched together and started to form a forest of palms. These are the tallest palm trees of their kind, with feathery looking palms, they make for an amazing sight as you walk amongst them and they are for as far as the eye can see.

This particular route is called Mirador la Glorieta, which as far as I can tell, translates to Glorious Viewpoint. It did not disappoint. The walk was very worth it, and we saw some great sights, from the forest, to palms that had been felled by time.

We then managed to hitchhike from this route all the way to the next one, called Mirador del Palmar, or Palmar Viewpoint. This route was even more spectacular than the first. Cars were parked at the end of it, where there was a sign indicating that the next part of the route was walking only. So far, our hitchhiking had saved us a walk of about 12km, and we had already got to see two of the main routes, so we put on our walking legs and headed down the 1km path.

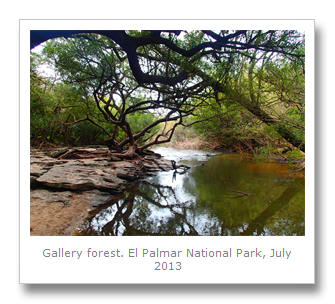

This path led all the way to a tributary of the Uruguay river which contributes to the sandy, wet and acidic oils that the yatay palms thrive in. The whole area of Entre Rios (between rivers) state which we were in, is called Mesopotamia by locals, as it is between the two large rivers of Uruguay river and the Parana river, and so reminded people of the Euphrates and Tigris in Iraq.

We skimmed some stones at the natural pool we found, and tried to avoid getting sand in ours shoes and set off again. There were some wooden walkways here making the route much easier. It was from one of these that bridged another small stream that we saw a capybara! It was the biggest one we had seen so far, and we also learned that they call them carpinchos here.

This section of forest is called gallery forest, because the trees touch each other in the canopy forming a microclimate underneath where diverse and unique species of flora and fauna are found. Of all the national park, only 60% is actually yatay palm.

We made our way back after saying goodbye to our new rodent friend, and tried to eat our sandwiches on a bench but it was too frustrating as it started to rain. Walking back up the track we felt a little miserable, but within minutes we were again picked up by some kind Argentine tourists who whisked us to the next and final route of the park. We were so lucky, we had seen all three of the routes, which should have been a walk of about 18km, but we walked only about 3km so far! Result!

The last route was the least impressive but gave good views of the river, which was where we now were. We spent 10 minutes or so there and decided to try and make for the final stop which was where the admin office, restaurant, beach, museum and also some Jesuit ruins were! And again, we were lucky enough to get a lift with an Argentine couple who took us all the way we were going! Phew! This certainly made up for the bad luck we had at the Monte de Ombues.

When we arrived, however, the guy who gave us a lift turned to me and asked where I was from. ‘Inglaterre’. I replied. ‘Londres’. He said ‘Usted sabe la Guerra de las Malvinas? Luché en ese!’ roughly translated as ‘You know the Falkland's War? I fought in that!’, as he raised his hands in a rifle-holding gesture and went ‘bang bang’. I just said ‘Thanks for the lift.’ with a smile, and we set off to eat our sandwiches quite quickly, before the conflict could restart.

The rain had eased off somewhat now, so we enjoyed our food outside at some picnic tables. The food at the restaurant looked good, but it was also a little pricy so I was glad we had our own food. Some of the crazy birds we had seen at the Iguazu Falls came and landed on the branches above us. These birds, plush crested jays, were fearlessly trying to steal someone’s sandwiches at Iguaza, so we jealously guarded our food until we had finished. I was then dumbfounded to see another Ombu tree! Not only was this one sitting right there, but it also had a big sign next to it, too ‘Ombu’.

After checking out the restaurant and the attached gift shop, we decided to look at the final trail which headed to the old Jesuit lime factory and to the river’s beach.

This area was originally settled by the Charruas natives, who were hunter/gatherers. Since the Uruguayans killed them all, we know very little about them, even their name ‘Charruas’, is a Guarani name, meaning ‘enemies’. How sad that a people’s history, and name, were totally obliterated by this genocide. The Guarani were the natives the Jesuits decided to ally with and convert; ostensibly for usage as indentured servants, and at the Calera it was no different. The Calera is the name for the lime making plant that the Jesuits built at El Palmar around 1650 to 1700.

The trail runs next to the river for about 1km until you finally get to the ruins of the Calera, and there are information boards, in Spanish, posted along the way. We saw some beautiful flowers, and the ruins were pretty interesting. The orange trees were fragrant and the beach was pretty cool too. The river here was pretty black and murky though – a product of the agriculture upstream in rural Brazil. The silt and eroded land from ranching and slash and burn further upstream deposits the silt along the banks of these rivers all the way to the Rio de la Plata and Buenos Aires port. That is the self same silt we saw spilling over Iguazu falls, whereas when the first Europeans arrived they reported the water being completely clear. it’s amazing the negative impact the Europeans had on the inhabitants and environment in such a short time.

We decided we wanted to head back whilst there were quite a few people around, in the hope of getting a lift the 12m back to the road. We were going to try and flag a bus by the side of the road back to Concordia. Luckily, two park rangers were going back our way and so we got another lift within 10 minutes! We were a little unluckier with the bus, having missed one, we ended up waiting in the cold for almost 2 hours before we got our bus, but it was cheaper than getting a taxi.

We got back to our hotel, and we had had the best day! Francesca got to see her ruins and Jesuit history, and I got to see my yatay palms! The weather was not great for the photos, but the next day, 21st July, as we left Concordia for our next destination, I managed to have the camera ready as we drove past El Palmar and got some great shots with a blue sky (only some clouds). Perfect start to our Argentina trip!

No comments:

Post a Comment