While it seemed like it was going to be a bit of a push, on the 15th of July we decided to head to the city of Fray Bentos for the afternoon before moving on to Salto where our hotel was booked for the evening. We gathered together our things, leaving behind Colonia and boarding an early morning bus to Fray Bentos, a city of 22,000 people. We got to Fray Bentos and took a taxi to a former meat factory – our museum destination for the day - with all of our bags. Thankfully we were able to store them on-site while two guides, one technical guide and one English-speaking guide, led us around the grounds. We later found out our group was our English-speaking guide’s first tour – we hadn’t even realized because she was so informative and could answer all of our questions!

I wasn’t aware of it, but Colin later told me that he knew there was some meaning behind this city’s name – Fray Bentos, while originally the name of an immigrant priest who moved to Uruguay (translated the name means ‘Friar Benedict,’) is also the name of a British meat company now owned by Scottish food group Baxter’s. The company has flat-lined in sales for the past 10 years and management has bounced around between numerous groups including Campbell’s from 1993 to 2006 and Premier Foods from 2006 until 2011 when the brand was acquired by Baxter’s. While the company may not be as solid as it used to be, it is still pretty well known.

Because of this the five-story high industrial processing plant that used to process meat for Fray Bentos has become the best known museum in the city. Originally a meat salting warehouse, the plant was owned by the Liebig Extract of Meat Company or Lemco, a company founded in 1863 in London. The plant was named after Justus von Liebig who was a German chemist who invented one of the main products produced by the factory in Fray Bentos. This product was a meat extract which could aid poor people of Europe to purchase meat. Liebig, being a chemist, experimented with various meat ‘tonics’ and invented the cooking aid we know as the bullion cube, in a liquid form. Since the extract required a ton of beef to produce (32 kg of beef were needed to make just 1 kg of the extract) Liebig and his friends went into the cattle processing business to expedite their venture. They decided to bring their business to South America due to the abundance of cows in the area. The group found a meat salting factory and decided to turn it into a processing plant for Liebig’s extract. Because of the factory’s position along the 16 meter deep Uruguay river (and thus, directly adjacent to the shipping harbor) the meat shipping process was extreme efficient. During World War One, the factory supplied the Germans with meat for their troops and processed record amounts of meat; a record 208,980 animals in 1890. They also produced bullion cubes for the Germans, which the soldiers would mix with hot water for a quick soup.

Lemco was eventually acquired by Vestey Group a group of UK food companies, after WWI in 1924, and the factory space stayed in operation renamed as Anglo for 117 years until 1979. In an interesting twist, during World War Two, the formerly German-owned factory helped supply the British troops in their fight against the Germans. The now British-owned factory shipped more than 16 million cans of Fray Bentos corned beef to their troops which helped solidify the brand as an important staple of the British diet. After WWII, the factory was abandoned by the British because of new taxes introduced by the Uruguayan government which decreased profit. After the factory became dilapidated, the British sold it to the Uruguayan government for $1 million USD and it was turned into a museum.

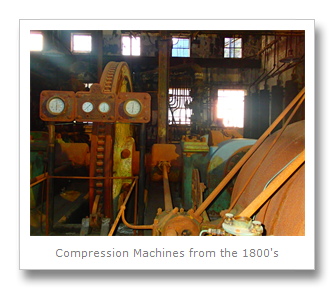

The first stop was to a huge warehouse-like space which included both German and British machinery from the early 1900’s. This room was called the compressor room. The first part of the compressor room, which had a dilapidated ceiling and therefore we could not enter, held two German-made machines for compression. From what I could understand these compressors generated electricity from the energy stored in air under pressure. This energy was used to power the plant as well as provide power for the entire city of Fray Bentos at the time.

The rest of the room held four British-built compressors (built by Cole, Marghent, & Morley Ltd. in Bradford, England) which had been added by the British once the plant came under their control after WWI. These compressors operated by burning coal, similar to a steam-train engine. There was a huge wheel (shown in our photo below) which worked with the steam produced by the boiler to generate energy. There were two of these massive wheels in the factory so they could stay in operation full-time without burning out. Because of the heavy usage, the company needed to keep adding capacity to the energy production process.

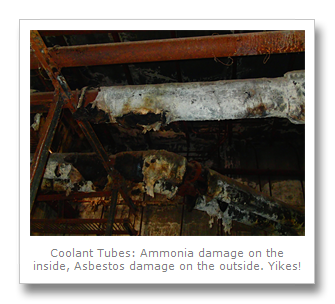

The compressors also provided energy for the coolant system which pumped ammonia through 7 kilometers of tubes around the factory, both cooling down the working machinery and helping to cool some of the meat contained in storage rooms which we would explore later. Ammonia, a colorless and pungent smelling gas that is a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen, is commonly used in the industrial process despite being a highly dangerous and corrosive substance. Because of its ability to act as a refrigerant, its high energy efficiency, and low production cost, ammonia was used by Lemco/Anglo in the meat production process. While walking through the large space, I noticed something interesting and called Colin and our guides over to take a look. Many of the tubes had insane corrosion damage on them, presumably from ammonia being run through them for so long and poor maintenance once the factory stopped production. In addition, the tubes were covered in asbestos for insulation – as we now know, prolonged inhalation of asbestos fibers can cause lung cancer. Ok… time to leave the danger zone!

Back outside the compression room, we headed towards the real interesting part of the tour – towards the killing and processing rooms. Before we reached those, we stopped for photos outside of some warehouses and what looked like a big mixing vat while our guides gave us some more insight on how production was run at the factory. They told us that not a single part of the cow was wasted, and ingenious uses for the various animal parts ensured this. The animal’s hide was turned into leather products in another warehouse we could see from the factory. Animal fat was gathered together and washed, then scooped up from the top layer of a vat of ‘animal liquid.’ 1st class fat was exported, and the remainder was turned into soap and candles. Animal blood was used in soil fertilizer and sold as “guano” (guano is valuable bird and bat excrement used as fertilizer) even though it wasn’t true guano. Other parts such as the animal’s hooves were turned into glue. The most impressive is that all the processing for each of these additional products was done by factory workers on-site. Our guide joked that everything except the cow’s moo was used!

We continued our walk, noticing there were a lot of objects made out of steel around the factory, including some that didn’t make sense such as flat panels of metal placed into the ground which didn’t seem to be necessary. Our guides explained that when ships came to take away all the products produced at the factory – the meat mainly, but also leather, soap, and other goods, they came from Europe empty in order to have lots of space for the product to bring it back. The ‘empty’ ships had to bring something with them however, in order to have enough weight to remain controllable upon sailing. Thus sheets of metal were used as a ‘ballast’ or weight, and were placed in the bottom of the ship. The sheets weighed the ship down so it wouldn’t flip over and the metal was used later at the factory. Much of it was used to make factory tools – all of the hammers, axes, saws, and much of the simple tools needed for the blacksmiths were made on-site using these metal sheets. The sheets were also used to make hooks for hanging the animals and meat, and what was left over was used in repairing damage around the factory, hence the metal ‘repairing’ the ground beneath our feet.

Finally the four of us reached the killing and processing area. We first saw a holding pen where the 1,500 cows killed per day (200 cows killed per hour) at the factory were held overnight before their slaughter in order to keep them calm and unsuspecting. This is necessary because if the animals are stressed, there will be excess adrenaline in their bodies which will decrease the tenderness and keeping quality of the meat – and, let’s face it, isn’t very nice for the cows. Before being led into the factory, the cows were washed with a ‘rain’ of water from pipes above their holding pen. The factory slaughtered sheep as well – 2,000 per day or 400 per hour. In fact, this was the first part of the killing room we saw, which had sheep come in assembly-line style; they were hung on hooks, their throats cut by a large, spinning, disk-like machine, and the blood drained out in the first stage. The animal was then cut apart and separated out on tables into various body parts by factory workers who dropped the parts down holes in the floor; the wool was also dropped down. In addition to cows and sheep, rabbits, chickens, and turkeys were killed and processed for export.

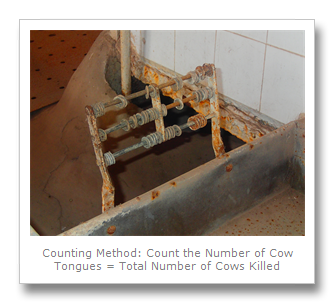

The cows were then sent down the assembly line hanging on hooks, the blood is washed off their slaughtered bodies and the parts are separated. The cows are skinned, their skin sent straight to the leather factory for processing. The meat itself is weighted without being removed from the hook, as the scale accounts for the hook’s extract weight. Finally, the various parts are sorted in the same manner as the sheep, and dropped down respective holes to the workers below. A very trusted employee worked in one special section where the cows’ tongues were sent for counting. The number of cow tongues told the factory the total number of cows that had been slaughtered in a given hour or day and helped the managers keep track of production speed and efficiency.

There was one factory room left to see after the canning area – a place called the evaporating room. This room had a huge vat for producing the meat extract invented by Liebig which would eventually be today’s bullion cubes. There was a multi-step process for evaluating and filtering the material that would make up the extract. Good meat extract went into the evaporators, while the ‘bad stuff’ was caught on filters.

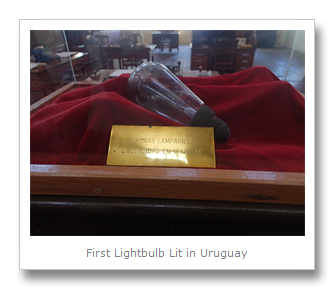

Done with the factory spaces, we decided to walk over to what was now (and then!) the administration area. It was really interesting to see people currently working in the offices that were once used by factory managers and officials. All of the old record books were in this area – taking a look inside one of them showed us the neat and meticulous records that were kept of production – impressive! There were old telephone switchboard machines, ancient copy machines that worked through physical pressure, even the first light bulb lit in Uruguay since the factory was the first provider of electricity to the area!

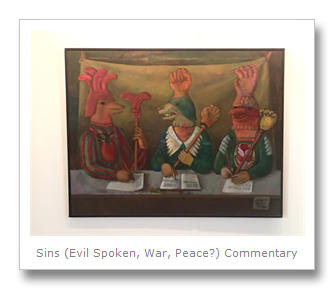

Our final stop was the museum which showed Colin and I a timeline of advertisements and packaging for various Fray Bentos products – all 200 different animal and vegetable products. There was also a huge mural on display which had colorful cartoon images telling the history of the factory, the war, and Fray Bentos’s role in it. The highlight of the museum was a two-headed calf preserved in formaldehyde which had been discovered by a worker inside one of the mother cows. They didn’t know it was pregnant – and definitely didn’t expect a baby with two heads!

We bought some snacks on the walk back to the bus station and waited for our journey to Salto. Next: amazing and glorious natural thermal hot springs and plenty of relaxation!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment