We found a hostel in Cuenca on the 12th January 2015 called Hotel Check-Inn. The location was OK, as was the relative price, but other than that the place was a bit loud and annoying. The center of Cuenca is a good-looking UNESCO World Heritage colonial town, albeit just as polluted as other cities and towns in South America. It was built in 1557, and was named after the then Viceroy of Peru’s hometown in Spain, although evidence of the region’s first human inhabitants has been dated back to 8060 BCE at the cave of Chopsi.

We learnt a lot about Ecuador’s first inhabitants at the city’s Pumapungo museum, located at the bottom of the historic center, and nestled in next to the river Tomebamba. The Tomebamba is one of the many tributaries East of the Andes that somehow makes it’s way into the Amazon basin, and dumps out into the Atlantic at Belem in Brazil.

The river is named after a city-state in the Incan empire that was overseen by native Cañari people who the Incas had conquered sometime in the early 16th Century. Like many other cultures in the region, the Cañari demonstrated a fierce resistance to the Incan encroachment, but interestingly were never totally removed from positions of power. It was actually through marriage that the Incans were able to insinuate themselves into bed with the Cañari officials, effectively conquering the territory through assimilation. This never sat right with the Cañari, and as soon as the Spanish arrived they waster no time in forming an alliance and ousting the Incans from the land, and helping in the Incan defeat just outside of Cuzco.

The museum itself is located at the site of Pumapungo (Door of the Puma) which was one of the seats of power during the time of Incan dominance over the Cañari people. A settlement has been located in Cuenca since around 500 CE, founded by the Cañari themselves, but it was the Incan ruler Yupanqui who had been offended by Cañari attempts of revolution, who ordered the site to be built. It became so grandiose that at it’s height it was apparently known as a second Cuzco, with gold plated buildings all over the place. By the time the Spanish arrived, however, it had been sacked and abandoned by the Incans, leaving nothing behind. This has fuelled speculation that it is the Pumapungo site which is the origin of the El Dorado myth, but that may never be known for sure.

The museum was pretty impressive itself, with several sections spread across numerous rooms and multiple floors. It was fairly linear, beginning with an explanation of how people settled the area, eventually becoming permanent residents with chiefs running the show. An exhibit of the rucuyayas that were found in the burial tombs of these pre-Incan peoples was on display – small wooden statues of people, that kind of looked like a pre-cursor to the Venus statues of the Valdivian culture.

In fact the regional culture of the people leading up to the emergence of the Cañari was pretty similar to what we had seen all over the Andes, even in modern times. Terraced agriculture (Cuenca is at 2560 meters above sea level), widespread trade of familiar goods such as the Spondylus shells, and administrative centers of power, doubling as religious symbols of control. The system of administrative oversight was known as caclgazgos, and became large enough to be ruled by a Kuraco, or regional overlord.

Once Inca Yupanqui established himself at Tomebamba and built Pumapungo, it was the beginning of the end for the Cañari - Yupanqui’s son was even born at the site. Huana Capac, the son, expanded the site, adding more splendor and adornments until it became utilized as his royal palace, with natural baths and canals built as well.

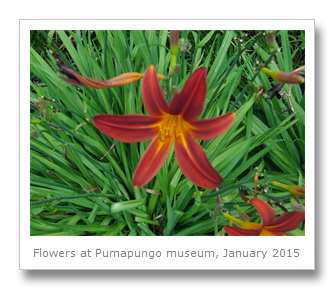

Behind the museum we found the grounds of Pumapungo itself, which is open to the public. The grounds were kept immaculate with a large variety of flowers, trees and even agricultural plants to walk around. We walked among what is believed to have been the High Temple, called a Qurikancha. Now ruined, the information board described it as once an administrative center, center of worship, political building and even an astronomical observatory! I didn’t buy that at all, but it funny to see how the archaeological sites in Ecuador try just as hard to inflate the importance of the site by over-emphasizing the list of what they actually do. One example of this was a picture of surrounding mountains (that we could not identify as the ‘picture’ was just a drawing of the horizon). The picture was on an information board that said lines called ceques linked the Incan ruins to the mountains. No evidence of these ceques were presented, and the board even said that they were “imaginary”.

The beautiful gardens wound down across the site to a little exotic bird aviary where we saw some amazing little critters. Lots of different parrots were hanging out including Orange-winged Amazons, Yellow-crowned Amazons, Red-masked and Canary-winged Parakeets. We saw Black-chested Buzzard Eagles and Savanna Hawks, but our favorites were the Plate-billed Mountain Toucans and the small Toucan Barbet that we saw.

Inside, the museum had a lot more to offer than just pre-Incan history. There were displays on a whole gamut of cultures represented within Ecuador’s borders, from the Saraguro people we had already visited, to the Shuar tribes of the lowland Amazon Basin. The Shuar are the tribe most famous for being headhunters, and the museum even had some human and Sloth heads on display, that had been shrunken. These were called tsantsas (shrunken heads) – a practice which was banned in the 20th Century due to the increased popularity causing extremely anti-social behaviors. Fraudulent tsantsas, burglaries of mortuaries and even stories of outright murder put paid to the curio shops and black market trading in the heads.

The Shuar were once called Jibaros, an insulting word in the Shuar language, and it is this group that fired the public imagination with their usage of the poison curare dart, and are the only group in the world who had ever shrunk heads.

Next door, and more ruins. The Museo Manuel Agustin Landivar contains the ruins of Todos los Santos. The excavated site shows Spanish, Incan and, underneath the rest of them, Cañari ruins. The site was not that big and so we made our way through the Baranco neighborhood and visited the Museo de las Culturas Aborigenes. This museum needed a little more time – there are thousands of pre-Incan ceramics on display, grouped mostly by region or culture.

The collection started with fossils and minerals from the region, and even had lots of stuff from the era of the cave of Chopsi site. There was lots of pieces from coastal Ecuador, including Valdivian culture Venuses. Petroglyphs, lithic statues, ornaments, pestle and mortars and arrowheads completed their ancient stone age collection.

Most of the ceramics were pretty basic but some of them were well finished and pretty interesting. The earliest cultures represented were the Machalilla people, who would practice cranial deformation (just like many ancient cultures in Peru), and would bury their dead under a ceramic turtle shell. The Machalilla were around from 1800 BCE to 800 BCE approximately, but were located along the coast of Ecuador, whereas Cuenca is in the South, in the Andes.

The Machalillas traded heavily with the seemingly larger culture of the Chorrera people who are noted for the zoomorphic whistling ceramics. These jugs were made with molds, and often had stirrup style spouts – that is two openings from the jug connecting and forming one spout. A Northern volcano blew the Chorrera people back to the pre-stone age, but their ancestors soldiered on and formed the back bone of other civilizations to come.

The Tolita culture that the museum said existed from 500 BCE to 500 CE were found along the Southern coast of Colombia and the Northern coast of Ecuador. These guys were excellent goldsmiths, but the museum only presented some of their excellent small ceramic statuettes that depicted weird monsters – human and animal crossbreeds representing who knows what.

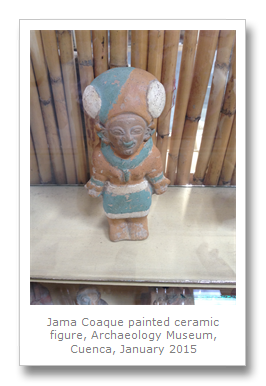

In the middle of the country, again on the coastal area, the Jama Coaque culture is said to have enjoyed a lengthy spell between 500 BCE (as contemporaries of the Tolitas), until 500 CE. Along with the Bahia culture, the Jama Coaque made lots of ceramic dancers. Some of these statues survived somehow – they seem very delicate – and are among some of the best examples of ancient ceramics there is. Ceramic rollers were used to apply patterns and paints to other ceramics, and there seems to have been an unhealthy obsession with cripples, the elderly and the infirm among these cultures (unless for some reason a medical training center that used the dolls to teach people about the illnesses somehow had helped survive all of these ceramics!).

Bones, bowls and ceramics were also displayed in the museum – some of the designs and patterns were amazing and the museum was well worth a visit.

We went to a pretty dismal cultural center after the museum were the staff were rude and impatient – but there were some OK masks and figurines of the Ecuadorian carnival though.

We made our way back up into the heart of the historic center and ended up in Calderon Park which is the main plaza where they have not one, but two cathedrals. There is one that was built in 1557 and the other was built in 1829 (imaginatively called the old cathedral and the new cathedral, respectively). The old cathedral’s main claim to fame is that it was used by the French Geodesic Mission in 1736 as one of the landmark’s to help determine and measure the length of a degree of latitude (because of it’s proximity to the Equator).

After getting Francesca some contact lenses and spying some shark cartilage in a local ‘pharmacy’ (no wonder the world’s shark population is decreasing so much), we both headed over to a local artist’s gallery-cum-shop-cum-house, called Prohibido Centro Cultural. Eduardo Moscoso was the artist but he was not at home – however, his home was pretty awesome, if not gothic and a little weird.

Pretty much next door was another local curio called Laura’s Antiques. Basically these local guys all had just turned their houses into attractions for people to peruse. Laura’s Antiques did what it said on the tin and was filled with antiques from top to bottom. Not just any old antiques either, but loads of artistic and surprising objects, along with bits of old tat, along with a couple of kids watching television – you are walking around their actual house, which can be a bit awkward.

Our last stop was the Baranco Hat Museum. Sounds boring, right? Well, not many people know, but the Panama hat is not actually from Panama, it is from Ecuador. It was first produced in the 17th Century and is woven from the reeds of the toquilla palm. The best toquilla palms are from coastal Ecuador and the finest hats are made in a town called Montecristi. Cuenca’s factories are also known as some of the best, producing a variety of styles, colors and qualities. The finest hat is supposed to be able to hold water, and when rolled up for storage, will pass though a wedding ring. The grades of qualities vary from vendor to vendor, though, so there is no real standard from which to compare. We watched them shape some of the hats for their customers, when I got the bug and bought a rather nice and traditional Panama hat – or sombrero de paja toquilla, as they are known in Ecuador.

When the hats used to be shipped from Ecuador, the vendors did not think to put anything on the boxes they were shipping. The workers at the docks at the Panama Canal received all the boxes, and so just stamped “Panama Hats” on the crates – and that is what the world came to know them as.

Phew! That was just one day’s worth of activities, and the next day, 14th January, we ended up going out for more! The skeleton museum was first on our agenda, and we ended up seeing the animals of South America without their skins. We weren’t really supposed to take photos, so ours were a little blurry – but you can see a Toucan skeleton which is cool!

Francesca checked out a modern art museum and then also visited another Panama Hat factory later that day. This one had a bit more background about the history of the hats. Spaniards in the coastal regions of Ecuador admired the hats the natives wore for their toughness and flexibility. They were made of reeds, but were of a different style than the Panamas of today. In 1630 Francisco Delgado convinced some locals to make the Panama as it is today with their quality reeds. They agreed, but it was not until an economic downturn in the 1830s, when Bartolome Serrano ordered the creation of factories in the Cuenca area, that the hat started to be mass-produced, thereby creating a market worldwide. In 1944 the Panama hat was the principal export of the country!

On the 16th we took a fabulous day trip to a site that is described as Ecuador’s largest pre-Hispanic ruins. Ingapirca, or Incan Wall, is a few hours journey by bus from Cuenca. Like Pumapungo it is of Cañari origin, but was taken over by the Incans who used it as another administrative center and astrological observatory (probably to mark special events). The Incans co-ruled with the Cañari at Ingapirca, and the development of a clever and intricate hydraulic irrigation system sealed the deal for the site to become at least one of the most interesting in the country.

One structure, now known as the House of the Virgins (Acllawasi), was once a rectangular building holding six rectangular rooms. Archaeologists discovered 30 female skeletons of a young age here – much the same as at other sites throughout the empire. The site is not all sex slaves and fantasy though. There were storehouses, residences and also farming land to walk around, but the best was the last – a large Incan tower with a round observatory. It is now thought that this doubled as a Sun Temple. Whatever the reality, the views were pretty incredible from the top.

From Ingapirca there was a trail that is fairly easy – although there were some steep climbs and muddy areas – which lasted about an hour. This looped circuit went past some areas of interest, including a series of water terraces carved into a rock (the explanations on the information boards were ridiculous, speculated wildly about the Incan spiritual cosmic view, and extrapolated all sorts of information that the evidence simply did not support without a huge leap of faith). The walk continued past farmer’s fields and buildings, through some lightly wooded areas until we came to a stone that had been carved like a Snake, one like a Tortoise, and one that was meant to be the sun, but it just looked like a natural part of the rock. A cliff looked vaguely like an Incan man’s profile from the side, but it was a stretch – this trail was a bit gimmicky.

The views were nice, however, and so were the hard-working locals. We finished our visit by eating at a café, and as the museum at the site was closed semi-permanently, we head back to Cuenca.

The next day we took a taxi out to a zoo, unique in that it was set up on the side of a hill. Many of the environments of Ecuador were represented with the animals from those regions living in open and natural pens rather than cages. Or at least that was the way it was sold to us. Some of the animals did not seem to have much more room than a normal zoo, and as zoos are not held accountable with regulation, it is difficult for customers like us to responsibly choose which zoo is good for a visit. As a rule, no animals should live in zoos, but it is difficult to decide whether the information we get from zoos actually helps conservation efforts or not.

We saw a Porcupine, which was a new one – spines everywhere, but asleep in a box. Spectacled Bears, Deer, Andean Foxes, Snakes and Llamas were all well and good, but then we saw some really cool Frogs. These were all South American and were very colorful, if not very small.

We saw Tapir, Monkeys, Capybara and finally, near the end, some big Cats. There was a beautiful Ocelot, and then there was a lot of rain. The paths down were very slippery after the rain – boots and patience are needed.

*******************

Francesca’s Market Day

On the 19th I went to visit a couple of market towns outside of Cuenca called Gualaceo and Chordeleg. Once I arrived in Gualaceo I walked up to a market high on one of the hilltops. Here I found loads of different strange fruits including cute little red plantains. One of the strangest (which I saw before in Bolivia) was a long green bean-looking fruit called pacae, which was a fuzzy white color and had a large black seed in the middle - which were available 5 for one dollar.

After the market I stopped at a separate market for lunch which contained a small dish of pork, onions, and other delicious goodies. On the way out I bought three small fried breads, one made of maize, one of trigo, and one of manioc. There were cuy grilling outside too!

After Gualaceo I hopped on a bus to Chordeleg. This town is known for silver and gold jewelry, specifically items done in filigree. I looked around at some really cool jewelry, including some Blue Footed Boobie earrings in pretty colors before deciding to buy similar (but much better) hummingbird earrings and a couple of little charms shaped like turtles for my collection. Once I made my purchase I got on the bus back to Cuenca, picking up some slices of pizza on the way!

*******************

Our last full day in Cuenca was the 20th January. We went and got a bus (again) from the horrible Cuenca bus station and got off at Cajas National Park. We chose a crappy time of year to visit, as most of the time it is raining. Cuenca is high, but Cajas is higher at well over 3100 meters above sea level (some of the park is over 4400 meters), and so it was hard to breathe or hike. There is some confusion over the origination of the name (Cajas is Spanish for boxes). Some say it is because the many lakes located in the park look like boxes, but considering the Quichua word cassa means ‘snowy mountain path’, it is more likely the name is from that.

The park has hundreds of lakes and lagoons – it is the glacial source of the Tomebamba river. There are also numerous archaeological sites, various mammals, and a large circuit trail which takes 3 or more days to complete in the wilderness. We did not see these things, as we only had the time and energy to do a short trail, just to get a taste of what the famous páramo is like.

Páramo is the ecosystem above the mountainous tree line but below the snowline. It is the land of the Puma. Unfortunately, we did not see a Mountain Lion this time around – but maybe we will be back. We walked a large circuit around the lake next to the entrance, which we found challenging enough! We saw a couple of Birds and a Rabbit, which was nice, and what is known as Polylepis (Greek for multi-layered), or paper trees. These trees have bark that looks like it is always peeling off – dense and layered for protection against the cold.

The rest of the walk was OK, but we did see a lot of scum in the water. These chemicals must have come from inside the park, and considering the park provides 60% of the town’s drinking water, it was a relief to be leaving the next day.

Some things about Cuenca – the nightlife is not at all like the reputation. There are only a few proper pubs, most of the bars being karaoke style, with drunken locals and undercover police. The only place we found that we liked was an English-run restaurant called Salvia Cuenca. The food was good as was the atmosphere (fairly quiet when we went there, which was nice) and service – but the location was a little annoying as we needed to get a taxi there. A word of warning to anyone traveling through or to Cuenca – the bus station is the worst in South America. Scams, lies and rudeness await anyone unlucky enough to have to enter – even the taxi drivers are on the take. Don’t bother trying to buy tickets before a trip, and make sure you have 25 cents per person in exact change to be able to pay the exit tax (no-one is willing to make change for you). Good luck.

No comments:

Post a Comment