On the 7th January we arrived at Zamora in the very South and West of Ecuador, which dates all the way back to 1549. The Spanish had to abandon the city once they had established it, due to the Shuar revolt of 1599. The ruins of the city were not found until hundreds of yeas later, and it was through the 1840s to the 1920s that people began resettling the area.

The drive from Loja is quite beautiful as we passed lots of rainforest to get there. The town itself sits on a confluence of three rivers, and one of the driving forces, other than tourism, which has bought people to Zamora over the years, was the discovery of gold.

We had been in contact with a bird lodge called Copalinga, and so we jumped in a taxi, after sourcing some food, and headed East out of town towards it. There was much construction going on, as there is in most of South America, but most of this was surfacing and widening roads. We had noticed two big Chinese hydroelectric projects going on further downstream, and so there were many workers all over the place.

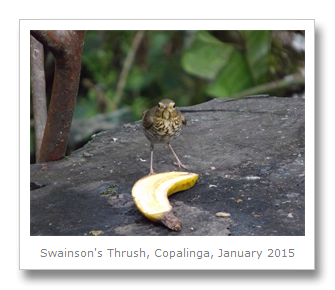

We arrived and met one of the owners, a man and wife (Catherine and Boudewijn) who were originally from Belgium. They bought the property twenty years ago and have been building on it as a business every since. The first thing we noticed were some bananas laid out on wooden platforms with the most incredibly colorful birds we had ever seen on them! We would soon learn all of their common names, thanks to some laminated information boards that the lodge has, showing all the birds that are common to see there.

Bird watching, or simply birding as it’s known, has an interesting clique of people associated with it, that we would soon come to know. Bird books are the most common way of identifying the birds that you see, and the bird book of Ecuador is a monster, as there over 1600 bird species that live in the country.

We just liked the birds and learning some of the names, so we were quite content to take pictures and see the stupid, but very pretty looking birds jump around and fill their faces with bananas.

The cabins we stayed in were very comfortable, and the place had hot showers, mosquito nets and even hammocks lying around. You did not need to go very far to see the birds, they were all over the property.

One of the first birds we saw was a Green Honeycreeper, which is annoying, because it was more blue than green, but that is a trend in birds, where naming convention often times misrepresents what the bird really looks like! Males and females are often different colors, as are juveniles, making identification all the harder!

The Honeycreeper is in the Tanager family, which comprises of small to medium birds, all sorts of different colors, which even includes Finches. Most species only live in a very small area, with 60% of Tanagers coming from South America, making it all the more difficult for birdwatchers (which I suspect is half the fun, of course).

That evening we got to see a very difficult to spot bird, which some bird watchers spend decades looking for but never see – the Grey Tinamou. This vulnerable bird is a ground bird, about 46 centimeters high, and is rarely seen. The owners of Copalinga have been feeding this one for years though, and the birds are now confident enough to come up, a few meters in front of a wooden blind we were hiding behind, and get snapped by the birding Paparazzi.

We had dinner in town at a place which served us a great asado, or BBQ. We had heard that the town was populated heavily by Saraguro and Shuar people, but we never saw any, at least not in traditional dress, so they must have assimilated completely. The only strange people we saw (other than ourselves), were the Chinese workers from the dams.

We bought some more supplies and headed back for some sleep. Before we could however, I found the largest moth I have ever seen in the bathroom. This thing was huge!

We decided to go for a short walk along some of the trails in the morning before breakfast. We saw the Grey Tinamou again, but it bolted away quickly – not difficult to see why they are so difficult to find. We were on the easy trail and it was quite slippery and difficult, so I am not sure what the difficult trail is like! The trails all go up into the cloud forest, but it is very steep, very wet and very muddy.

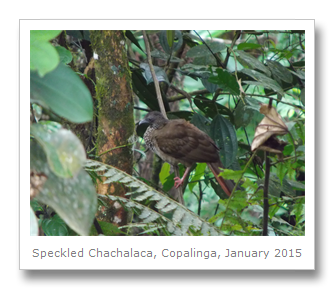

Breakfast was included in the morning, and it was delicious. It was nice to watch the birds come and go while enjoying some food ourselves. Some funny Speckled Chachalacas turned up – they looked like a Guan, or a Curassow, and they were very nervous – taking ages to build up the courage to approach the bananas.

There were so many different tanagers they were hard to keep up with. The pictures show off these photogenic birds better than a list will. We did see another larger bird at the feeders though – Russet-backed Oropendolas. These birds, relations of the Caciques, build long dangling nests that hang from tree branches.

One thing most of these birds had, is that they are all Passerine. This is the order of more than half of all bird species, and relates to the arrangement of their toes – three pointing forward, with one pointing backward, in order to be able to perch. This evolutionary step is thought to have been first encountered around 55 to 60 million years ago. The owner of Copalinga told us that these birds, when they squat down, automatically grip very strongly as a result of their biological make-up.

It was not long after we had finished eating, when a Cock of the Rock made an appearance. It’s stupid expression is always a delight to see, and it was staring down at us for quite awhile before it flew down the stream it was following, towards the river valley below. It was extremely orange with a huge crest on it’s head. That clearly distinguished it as a male, who use these attractive traits in displays of bobbing and squawking in a regular location called a lek. This one was more interested in what we were doing. They are well known for being very timid, so it was nice to see it hang around for a few minutes.

We decided to go for a walk before lunch, and so we headed out towards the National Park. The road goes for quite awhile above the river, but there are no more buildings after Copalinga, so the whole way is pretty peaceful. We saw a tiny frog, the size of my fingernail on the road. It was pretty well camouflaged, but I saw it hopping.

Francesca had bought some boots in town, and they were an essential bit of kit. Ecuador can get very muddy! We saw butterflies, some birds, Cacique nests and some very pretty waterfalls on the way to the park.

We saw strange bugs, and few people, and then we had an encounter with three male Cock of the Rocks! Those things are everywhere down here! Very timid though, so we did not get any good photos. On the way back we caught some glimpses of a Sickle-winged Guan.

The next day the Cock of the Rock came back for breakfast! We got some better pictures, but the light was not very good so our photos were a bit blurry. Resolution: get a better camera!

Other birds we saw (not pictured) at Copalinga, were the Summer Tanager, Bananaquit, Orange Bellied Euphonia, White Lined Tanager, Golden Olive Woodpecker and even a White Fronted Dove.

After another hearty breakfast, we spent the morning with the owner, Boudewijn. We had asked him to show us his hydro-electric set-up, and it was a good thing we did, because it was fascinating how he had built a system, over several years, with no prior relevant knowledge. The system had evolved (appropriately for Ecuador), and had become a successful example of conservation, results from hard work, and self-sufficiency.

The first thing we saw was a manual by Adam Harvey, which was called the Micro-Hydro Design Manual. The owner told us he had to read this book several times before he could understand enough to be able to build his own system.

The Copalinga couple had made a good choice in their appropriation of this property. It was between two streams. One provided drinking water, the source of which was on their land, and so would never get contaminated by other people (they had sent the water for chemical analysis to ensure it’s purity). The other, a larger stream, did have people living upstream of it, but it was to be used only as a source of power.

Not much water was diverted to the turbine that produced the electricity for the lodge (and the couple’s own house). This meant that the river would not be changed too much. Also, the pipes which carried the water down to the turbine were not buried, but rather placed carefully to ensure that water flow was at an optimum speed for driving the turbine. In this way, no tree roots were cut either.

The turbine itself was nothing shot of genius – he had designed the spoons which sit inside the turbine. These spoons are turned by the water extremely rapidly. Tweaking of the design was necessary to ensure the maximum force hit the spoons without damaging them too much through wear and tear. Molds were taken of the spoons, and local metalworkers were sourced to create the spoons in bronze. Easier said than done in a country like Ecuador – especially when they don’t really understand what you are trying to achieve.

We took a look at the turbine housing. Up close you could hear the turbine, which Boudewijn said he could always hear anywhere on the property. It was built so well though, that we could not hear it from the cabins, making the place seem very peaceful. The turbine had to sit in a concrete casing to ensure stability and balance. An alternator and flywheel were present, to aid in electricity generation, and to give balance and prevent overload, respectively.

The electricity went into a cabin that Boudewijn had built. A Siemens machine acted as a circuit breaker and allocated the electricity as needed. To prevent electrical overloading, for example when a washing machine is on, the electricity was allocated into other places when not needed, such as a drying room (heaters and light bulbs were used).

It really was a great system, and visitors to Copalinga who had worked on large scale hydro projects before have told Boudewijn that he should be proud of it.

He also put a lot of work into reforestation around the site. Cattle farming had left it’s mark on the area, but you could almost not tell, as Boudewijn had already reforested much of it. To get rid of the bracken areas, he planted pioneer plants that would provide shade to kill off these difficult weeds. Once they established, he then started experimenting with different trees, cut from the forest itself, to explore the quickest way to repopulate. Some of the trees were mature only after decades, so it is a testimony to his fortitude that this secondary forest has already seen mammals returning to it. Their camera traps even show Ocelots and Pumas having returned to the area.

This kind of ecological brilliance (hydro self-sufficiency couple with terraforming) should be a template and inspiration for many places all over South America and the world. Hopefully this story will inspire others to see what is possible with just hard work and a little time. The reforestation only took a decade, which is very quick in terms of reforestation.

That night we followed the directions of the lodge and walked down the road (15 minutes) to wait for a Blackish Nightjar. We had scared it off the previous night, so we were keen on seeing it this night. Apparently it is quite rare in the Western Amazon, so we were lucky when it turned up and started hunting insects from it’s perch.

That was our last night at Copalinga – we had wanted to stay another night but we got a bit fed up after an unfortunate incident when the owner, Catherine, embarrassed me in front of other guests by insinuating that I was somehow cheap for not buying alcohol from them (because I had bought my own), I could not sit with other guests (because they might feel awkward as they had purchased expensive booze from the lodge, while I had sensibly bought it from a shop in town), and that I had to drink my beer in my room, like a child. I felt this was very rude to say in front of other guests, especially as they had not mentioned anything to do with rules about drinking anywhere in their literature, or face to face when we arrived.

I think it was more likely that she was stressed whilst making dinner for these other guests, and when I came back from the Nightjar walk, she was annoyed as I was in the way, or at least she perceived me to be. I remember her being a little off before I even got my beer out. The lodge doesn’t seem to want to create definitive rules about drinking alcohol because it would draw attention to their over-priced menu I guess, but they should be definitive, because awkwardness and embarrassment are two things I neither sought nor deserved. Other than that unfortunate incident, I would still recommend the lodge to backpackers on a budget, because the location and the bird watching are excellent, and that is thanks to the bravery and fortitude of the owners themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment