On October 24th Colin and I decided to go to a few more attractions around Lima. We started by taking a taxi early in the morning out to the pre-Incan temple of Pachacamac. Pachacamac is 17 pyramids built in the years of 800-1450 CE and eventually taken over by the Incan empire. The pre-Incan civilization used Pachacamac as a temple for the worship of the Pacha (earth) Kamaq (maker) their creator god. Throughout this temple there was a water system which channeled water from springs throughout Pachacamac. There was also a system of roads running through the complex delineated by tall walls of stone and adobe on either side of the pathway. These roads divided the city into four sections of east, west, north, and south. When the Incans took over the temple of Pachacamac they incorporated the god Pachacamac into their pantheon, considering him lesser than their own god Viracocha.

There was a self-guided walk we could do around the temple, which was unfortunately nearby a town across the highway. People from the town dumped their trash across the road in the temple complex, so some parts of the temple walk were filled with the stench of rotting trash and the sight of birds picking through it.

The first temples we stopped at were the oldest of the complex, which supposedly served as an administration center. Like other temples in and around Lima these buildings were built with the ‘bookshelf’ technique where small ‘books’ of adobe are lined up together to form the building structure. Towards the end of the buildings’ use the area was used as a cemetery by the Yschma people. When this area was excavated in 2004 more than 300 burials were uncovered, including one massive funerary chamber contained over 100 individuals and their possessions.

The next temple building was a much more recent construction in 3 parts, completed by the Inca in the 1400’s.This building had numerous patios, Incan niches, and ceremonial ponds. It is known as the ‘Mamacona’ and was used as a sanctuary or place of worship for women “dedicated” to the Incan Sun God, as well as for the production of temple goods.

The first grand pyramid we reached had a large ramp running from the ground up to its entrance. We do not know the function of the pyramid, but it may have been an administration building or a palace. Inside the pyramid were various rooms, including some storage spaces and ‘buried deposits’ probably meaning tombs were found in the pyramids.

The second grand pyramid was actually three large buildings surrounded by numerous lateral buildings and a large closed patio. It is 210 meters by 50 meters in size and was likely constructed by the Yschma culture sometime between 900 CE and 1470 CE. Also built by the same culture at the same time was a third grand quadrangular pyramid with three ruined structures and two large patios closed by a perimeter wall.

Eventually Colin and I reached the Palace of Tauri Chumpi, a residential building with two connected plazas connected by ramps. While the Incans used the building it is not known if they constructed it or if it was constructed by a previous culture and simply appropriated by the Inca for their own use. According to chronicles written by the Spanish this palace was the residence of Incan nobleman/administrator Tauri Chumpi who was in charge of managing the local populations and of the redistribution of goods and resources throughout the valley. This part of the complex was excavated in the 1960’s by Alberto Bueno, who found multicolored textiles, fans. There was also another structure called the ‘Casa de los Quipus’ where 34 different quipus (knotted cotton handheld accounting systems) in various colors were found.

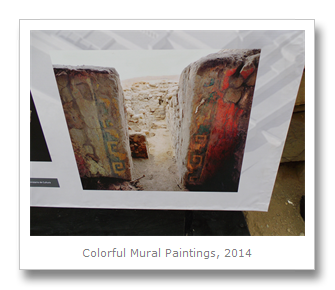

Parts of the site had paintings, including one 6 meter tall ‘Painted Temple’ - a rectangular adobe building (adobe bricks covered with adobe plaster) with has different designs painted on it, namely red and yellow designs outlined in black. These designs include anthropomorphic figures, as well as fish, birds, and plants, painted sometime between 200-600 CE. Unfortunately the paintings were mostly covered by a protective banner at the time of our visit. In the Painted Temple there is evidence of a platform with a special chamber, which supposedly was used to house a wooden idol of the god Pachacamac, and may have even been the location of the ‘Oracle of Pachacamac’ – where followers of the god Pachacamac would give offerings, receive advice, and ask for things from the god and his priests/priestesses.

There were also some colorful painted figures of humans as well. Near some of these painted areas in 2014 were found Incan-era objects from all across the Andean region, indicating this area may have had some significance for pilgrimage.

After the period in which the multicolored frescos were created, there is evidence that the Huari people built some structures within the city between 600-800 CE. Beneath and in front of the painted frescos was found the ‘Max Uhle’ cemetery – perhaps the most important one in the temple complex. This cemetery and its’ Huari-influenced designs, plus different Huari style ceramics and textiles found in the graves, give evidence of the Huari culture’s previous presence.

The remaining majority of the buildings were built after the Huari’s influence, in the period between 800-1400 CE, just before the conquest of the Incas, followed by the Spanish conquest. When the Incans invaded they conquered and incorporated the Yschma people, the then-current residents of the Pachacamac temple, into their empire. Once the Incans took over the temple they added even more structures to it.

One of the major Incan constructions at the site was the Temple of the Sun, a promontory adobe structure looking out at the sea. The temple walls used to be covered by a layer of red plaster, and some of the red can still be seen. At this temple were found human sacrifices and offerings in the temple niches. As we climbed up to the temple and walked around the pathways of the Temple of the Sun we came across two islands in the sea in the distance, and stopped to read a myth collected by Father Francisco de Avila in 1610 about their creation:

This myth explained that a god named Cuniraya traveled around the Earth teaching people agricultural knowledge. One day he fell in love with Cavillaca, a beautiful woman who wove under a Lucumo tree. Cuniraya placed his seed in a lucumo fruit which Cavillaca ate. She became pregnant and gave birth to Cuniraya’s child. Cavillaca called all the gods to her and asked her child to find his father and he found him – Cuniraya sitting dressed in disguise in ragged clothes. Cavillaca was disgusted a pauper was the father and she ran with the baby to the sea to throw him in. At the same time Cuniraya unveiled himself as a god in beautiful golden clothes, running after Cavillaca. Cavillaca jumped into the sea with the child and they both turned into stone islands out in the sea.

We climbed down from the Temple of the Sun to a plaza below it known as the Plaza of the Pilgrims, another adobe structure which formerly contained a thatched roof. After exploring this area, Colin and I caught a bus back towards the center of Lima. Quite hungry by then, we went to a mall for some Subway sandwiches before heading to the nearby Museum of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru (BCRP.) This museum held a few different collections – one of the Macera-Carnero folk art collection and old pottery pieces, one of bank notes and coins, and one of artwork.

Downstairs in the museum was an important collection of pre-Incan pottery from a variety of different cultures. Since I’ve written about these cultures as we’ve visited their respective archeological ruins, I’ll just show examples of some of their best pieces from the museum here:

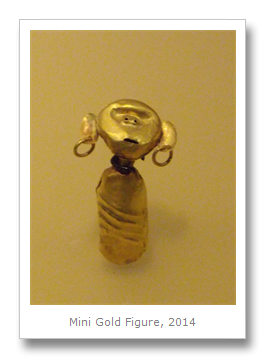

There was also a stunning gold collection in the bank’s guarded safe-room. In this room on one of the walls was the ‘Myth of Vichama‘ which explained that the locals told the Spanish that the Vichama begged his father, the Sun, to create humans. The Sun sent him three eggs – a gold, from which the nobles and their deputies came, a silver, from which these men’s women came, and a copper, from which the common men and women came. This myth shows how the locals considered various metals as very important. Rather than mainly for commercial use, the locals used metals primarily for religious ceremonies, to represent different ethnic groups, political affiliations, administrative positions, ancestors, and in stories supporting the transmission and belief in their mythology. Gold was also used by the Inca to reward their provincial governors. Some governors received shirts decorated with gold or with silver, as well as bowls, drinking vessels, and bracelets made of gold and silver.

At the exhibit we witnessed the only known Nazca (300-450 CE) metal object – a 30 cm wide silver plated gold nose ring belonging to a Priestess. There were also a selection of gold tumi knives, used to spill the fertile life liquid of sacrificial blood on the ground.

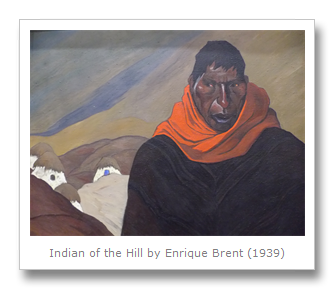

Upstairs we saw paintings from the Republic period. There were also some of the popular “costumbrismo” paintings – watercolor paintings of local characters and customs of ‘people on the street.’ Many Peruvian artists ended up studying in Europe eventually, spreading the images of their local culture throughout the continent. Some of these artists brought their knowledge from Europe back home and represented their support against actions taken by the Peruvian establishment through their work. In the 1940’s Peruvian artists’ work took an avant-garde style, which shifted to abstract art in the 1950’s, then pop art in the 1960’s. In the 1970’s the Peruvian government put restrictions in place on cultural expressions, and art returned to a surreal form. The growing political tensions continued and by the 1980’s the violent air spilled out into the art as well. Here are a few of the more interesting images we saw:

I stopped for a quick look at the coins on the way out of the museum. In the 16th century coins were issue by the Spanish King through the King’s sanctioned Royal Treasury’s ‘Lima Mint,’ founded in 1565. When Peru became independent in the 1700’s they issued their first coin, San Martin’s Peso, in copper. Some of the literature explained how Peruvian coins and monetary policy were stabilized with the creation of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru in 1931. One type of bronze currency was created called the Sol, and 50 years later in 1985 the silver Inti currency came into circulation. In 1991 a new silver Sol was put out, with smaller denomination coins in brass.

After the bank museum I decided I wanted to take a quick look at Lima’s Food Museum. It was an annoying visit, as they were near closing time and didn’t tell me that before I paid for my ticket, so I was left to rush a bit through the exhibit. On top of that the camera battery kept dying so I had to alternate between charging it a little and then rushing to take a couple more photos of the exhibit! I managed to make it through though, and learn a bit more about Peruvian food I still wanted to try. Here are some photos of the dishes and their descriptions below. Click on the name of the dish for a link to a recipe I found online about how to make it!

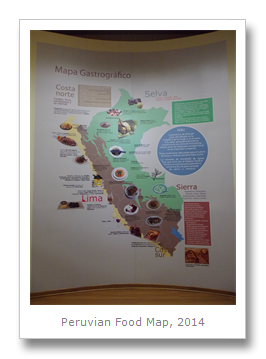

The main section of the museum discussed foods from all the different regions of Peru. It began with a big map which charted where each dish came from, then showed photos of the different regional dishes. There were also models of modern Peruvian staples: chicken, aji, and potatoes.

The next section had loads of different Peruvian breads, sweets, and bakery treats on display.

Amazon Food

On display in the museum were a collection of Amazonian dishes. The first pictured was inchicapi (a chicken soup with peanuts, coriander and manioc) and a group of mushy packets called juane (containing boiled rice, meat, olives, and hard boiled egg wrapped in a leaf.) A few other Amazonian dishes are tacacho (a roasted banana dish served with bits of pork, similar to bolon de verde from Ecuador) and zarapatera (turtle meat served with boiled cassava and plantains, both cut into disks.)

Andean Food

There were many Andean dishes, or mountain dishes, on display in the museum. One we tried before was rocoto relleno (a large rocoto peppers cooked to remove its spiciness, then filled with hard-boiled eggs, melted cheese, and ground beef and pork mixed with onions and pecans) and chiriuchu (a cold mixed plate of cuy (guinea pig), chicken, jerky, sausage, cheese, algae, fish eggs, torreja (a type of omelet), and cancha (toasted, crunchy corn kernels) topped off with a slice of spicy rocoto pepper.) Ocopa (potato and hard boiled eggs with olives all coated in a green sauce of huacatay (black mint) mixed with peanuts and yellow chili) and adobo de carne (meat in an adobo sauce of lots of chilies, onions, garlic, vinegar, and beer.)

Coastal Food

Next I took a look at some of the popular coastal dishes of Peru. These first included on display were aji de gallina (chicken served with potato and hard boiled egg in a sauce of bread crumbs, aji, leek, onion, carrot, and tomato) and causa rellena (a layered compact dish of potatoes, aji, chicken or seafood, hard boiled eggs, olives, and avocado – served with sauces drizzled on it.) The latter of those we made ourselves at a cooking class in Cusco. I also saw some photos of parihuela (a seafood stew of prawns, scallops, and white fish – all seasoned with red and yellow chilies) and chicharrones (fried bits of pork belly typically served with sweet potato, raw onions and tomatoes, and dried corn.)

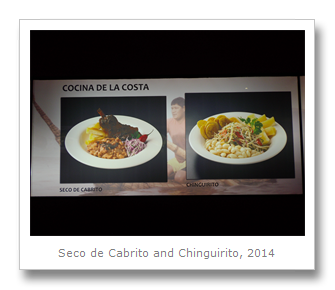

A few more coastal dishes displayed included seco de cabrito (goat in a sauce of blended onions, peppers, and tomatoes cooked in achiote seed oil, served with rice mixed with spices and achiote seed powder) and chinguirito (ceviche made with guitar fish, sarandaja beans, and cassava.)

There is a coastal dish is called shambar (a Trujillo soup of chicken, ham, beef, and pork skin along with wheat grains, fava beans, green peas, chickpeas, and dry beans, all seasoned with red and yellow chilies.) And one called chupe de camarones (an aji paste-flavored shrimp soup made with peas, rice, corn, eggs, cheese, milk, and potatoes.)

The museum went on to describe how Peruvian food has popularly been mixed with other cuisine styles around the world to create some really interesting fusion dishes. It has blended with Chinese food to make the Chifa stir-fry dish lomo saltado (beef, onions, tomatoes, French fries, and rice) and it has blended with Japanese food to make the delicious Nikkei tiradito (raw Japanese fish with Peruvian aji sauces.) Peruvian food has also blended with Central American flavors, African flavors, and Spanish flavors, as each group has given their own twist to Peruvian cuisine.

There was also a section on Peruvian snacks, including some interesting desserts. I can vouch for the ‘teja’ chocolates and the picarones but a lot of other Peruvian desserts (such as the purple corn pudding called mazamorra morada) are sickeningly sweet and way too slimy in texture for me personally. One dessert many Westerners might like is called Suspiro de Limena of meringue and dulce de leche.

After the food museum we were well ready to leave Lima and move on. Because of a few sick days and trips out of the city and back, we had been in and around Lima for nearly three weeks! It was time to get out of Lima and move on to the snowy mountains of Huaraz!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment