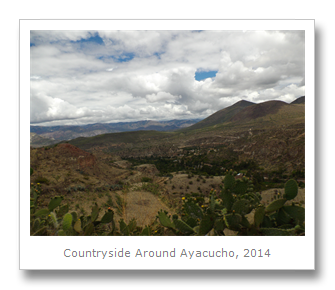

I went to the city of Ayacucho whilst Colin stayed behind in Lima to catch up on some work. The name of the city means “death corner” in Quechua because Ayacucho has been the location of numerous bloody battles. The Ayacucho region served as the capital of the famously warlike Wari empire, and is where the Peruvians fought the 1824 ‘Battle of Ayacucho’ for their independence. Also, in the 1980’s the area was one of the battlegrounds of the democratic government’s conflict with the Communist Shining Path organization.

I took the overnight bus from Lima on October 19th, arriving the morning of the 20th and making my way to my pre-booked hostel, El Balcon Hostal, in the city. The lady there was nice enough to let me check in straight away and provide me with hot breakfast delivered straight to the room! After some rest time, I headed out to explore the city and as many of its 33 churches (little corners of death, in their own right) I could manage.

As I walked through the city I kept imagining what it would have looked like overrun by Shining Path members. The Shining Path was a Maoist Communist party faction founded by an Ayacucho University professor known as “President Gonzalo,” which fought against democracy in a bloody attempt to install Communist rule in Peru. The armed clash between the Shining Path and Peru’s new democratic government resulted in almost 70,000 deaths of military personnel, Shining path members, and the indigenous community of Ayacucho – including many children. It was even discovered that soldiers tortured, killed, then cremated Shining Path members and indigenous peoples in four large ovens just outside the city of Ayacucho, now known as the “Cuartel los Cabitos” - yet another of Ayacucho’s ‘death corners.’

I soon made my way past the city gate and found a motorcycle taxi to take me up to a neighborhood called Santa Ana, which has a few huamanga stone workshops. Huamanga stone is white alabaster, and it can be used for a variety of different carvings. Some alabaster looks slightly translucent when light is shone on it, which makes for beautiful pieces. I managed to find a workshop where they let me feel how heavy a chunk was (not very) and watch how easily they were able to carve and shape the stone into little statues. While white is the most common, the workshop had huamanga stone in a few different colors.

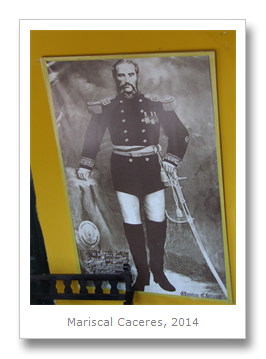

Huamanga stone is also sometimes used for gravestones and tombs – as is a cheaper stone called “cheqo pachecho” – I’m not really sure what kind of stone that is but I think we use it for driveways now! Once I finished at the workshops I went back downtown and managed to convince a Peruvian army general to let me inside a (closed for maintenance) colonial mansion known as Museo Caceres, which was being restored by the army. He had one of his underlings give me a tour around the place, which was formerly the house of Peruvian war hero Mariscal Caceres. Caceres fought in Peru’s War of the Pacific with Chile. There wasn’t much information about him at the house, but I did get to see a lot of tat he had collected – lots of old artwork and leather trunks.

Hungry for some lunch I hit the pedestrian zone and grabbed a set menu meal, then killed a couple of hours back in my hotel room. That afternoon I headed to the local University where I found a (closed yet again) archeological museum called the Regional Historical Museum Hipolito Unanue. Running on a good streak of luck, I again managed to convince the attendants to let me inside for a look around. In South America, ‘closed’ can sometimes mean ‘open’, and vice versa. This museum traced the history of people in the region since the lithic era.

The most interesting part of the museum was a section on the origins of the Wari people. According to the museum literature, the Wari people came about through a combination of the local Huarpa people, the Nasca people, and the Tiwanaku culture – who mixed religious ideas, art, culture, and social customs to become a new people. The growth and expansion of the Wari empire lasted from the year 500 CE to the year 1000 CE, until regional differences with the Wari capital of Ayacucho led to the city being abandoned.

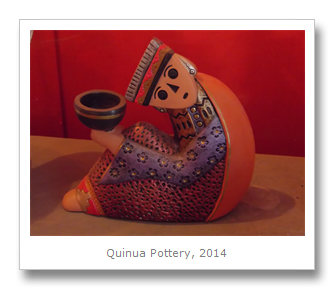

Wari people are known for their beautiful ceramics (since that’s pretty much all that has survived at burial sites) which remind me somewhat of the Nasca people’s ceramics. The Wari ceramics can be divided into two types – everyday home use and religious use. One pottery piece shows the principal crops the Wari cultivated: quinoa, potatoes, maize, tarhui, olluco, and mashua. Another shows faces from different ethnic groups in the area under the Wari control.

The museum also had a few mummies from the Chanca people who lived in 200 circular houses in the region after the Wari culture ended, and also mummies from the Inca who eventually conquered the area. There were also some stone statues of shaman and pumas that the Wari had carved for their capital city, to which I also planned to visit.

The next morning (the 21st) was my booked daytrip to see an awesome plant called the puya raimondii! These “puyas”, as our guide liked to call them, are a bromeliad which only grows at high altitudes (above 3000 meters) in Bolivia and Peru. Colin had told me previously that this plant is named after Antonio Raimondi, a scientist who classified and studied the plant. We had a little hike to get down to the plants but it was definitely worth it. Once we stood underneath them we could see how big the ones that were flowering at the time really were – some more than 10 meters! We were very lucky and managed to get photos of one of the plants blossoming with beautiful white flowers. There weren’t many tall puyas around since the flower dies once it blooms. Like the awesome rafflesia flower I saw in Thailand, this thing blooms very infrequently and is thus endangered and difficult to see.

After the small hike back to our van, we drove on to a lake known as Pumaqucha or “puma lake.” This very photogenic area not only has loads of animals around (lots of different birds, cows, and horses) but colorful flowers as well. Our guide explained that this lake was actually man-made in the Incan times, by Pachacútec, the same ruler who built the on-site archaeological ruins called Inti Watana where we were headed next. From the far side of the lake our guide pointed out where we could see a second, larger puya raimondii forest up on the side of the mountain. I was so glad there were a few much lower so we didn’t have to hike all the way up there!

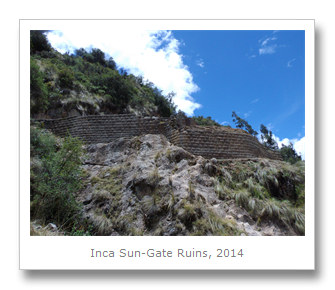

Our group walked around to the Incan sun-gate where we were able to get some fantastic views of the scenery around us. These structures were aligned to the solstice originally, and there were a few Incan-built fountains around as well.

The second part of the ruins was called Acllahuasi and consisted of some interesting carved stone stairs and other structures which had significantly fallen apart. It was hard to tell what the buildings were supposed to have been, though they still had their foundations in place.

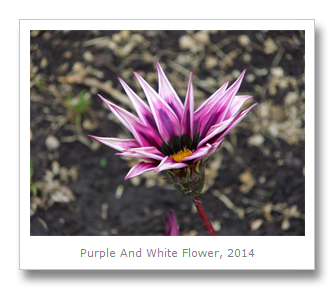

After finishing at the ruins our group drove on to our lunch stop where I enjoyed some boneless chicken chicharon pieces, which came with more of Peru’s famous potatoes and a few greens. Next we explored the main plaza in the town of Vilcashuamán. This town used to be populated by the Chankas peoples, before they were conquered by the Incans, whom I had read about in the University museum previously. Here we found a statue of Pachacútec, along with lots of colorful blooming flowers: a memory of this Incan-controlled period of the region.

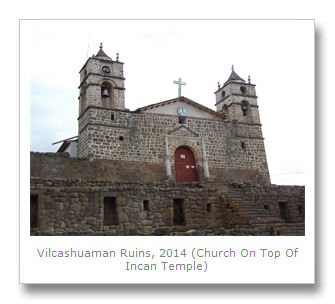

The ruins in Vilcashuaman are in two parts. The first being a Spanish colonial church built quite obviously on top of the former Incan temple that occupied the place, and the second a stone pyramid-like structure off to the side which had strangely been left somewhat more untouched than the temple at the main square. The church looked really odd, just plunked down completely on top of the Incan temple, with the many Incan niches still visible underneath. The silver and gold statues once inside were long gone, and these niches reminded me of the sad loss the Spanish caused to the Incans, and that the Incans caused to the Chankas, and the Chankas probably caused to someone else before them. We’re lucky there are enough pieces left to put together even a skewed historical puzzle!

Our guide explained to us that this pyramid, an ushno, is the only pyramid structure in Peru – but it could be argued that many other examples of pyramid-style have been found such as in the Nazca capital and in Caral near Lima. Though I do have to say this is the only stone pyramid I’ve seen in Peru, and the only pyramid that the Incans built to my knowledge. We were allowed to climb up to the top of the pyramid for a better look around, and noticed we could see what were possibly barracks or storage facilities below, as well as another sun-gate. The highlight of the pyramid was two stone chairs, clearly thrones for the Incan royalty.

The following morning, on October 22nd, I took another group tour which brought me to the Wari Site Museum. This museum included the ruins of the Wari’s former capital. We first went into the museum bit, which had some pottery and stone sculptures found around the ruins. There were even a couple of mummies from graves on the premises. Our guide pointed to a colorful cartoon map on the wall of the museum showing the little we know about the various stages of Wari civilization’s expansion and rule. The Wari conquered peoples around them, building a network of roads between their conquered areas in the process. However it was eventually nature which brought down these strong people – as in other parts of Peru, when the droughts came, the people abandoned ship.

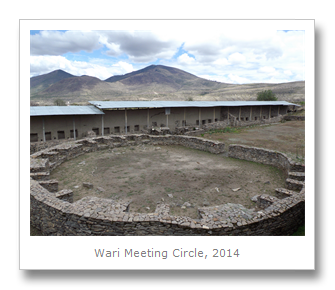

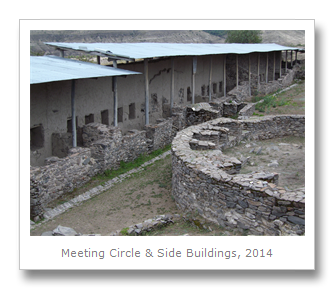

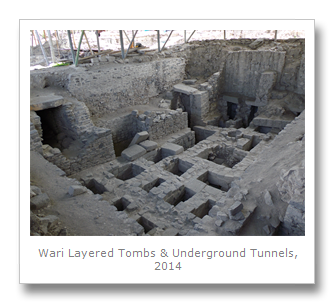

As we left the museum and walked around the ruins we noticed a large, flat stone tilted on its side. This stone is said to have probably been used for human and animal sacrifices – but nothing is certain. Once we reached the main circular building the site seemed to come to life a bit. There was evidence of white plastered walls along with tiny bits of color (reds, yellows, and white) left in certain areas, barely visible anymore. The main building area, complete with stone seating all around it, looked like it was a discussion or meeting area for numerous leaders. Other rooms, currently being reconstructed, looked like layered tombs. There was even an underground tunnel leading between the now-buried rooms, all throughout the building site.

In the distance we could see the Pikimachay Cave high up on the mountain. Evidence, including stone tools and animal bones (horse, guinea pig and giant sloth), have been found here of an ancient human settlement from as far back as 12,000 BCE. Another attraction in Ayacucho that looked like a struggle to get up to – I was very fortunate to get to see it from a distance as well!

We next stopped in the small Peruvian town of Quinua, which is known for its art and pottery pieces. Quite a few people in our group bought souvenirs to take back home, but I opted to have a look at the church and plaza instead. From the plaza you can see the giant monument in the distance commemorating the Battle of Ayacucho.

But before visiting the famous battleground our group stopped for lunch. It was here I got to try a fantastic new Peruvian dish! It included potatoes covered in a bright red sauce known as puca picante. This sauce is made from beetroot and peanuts, and it was actually not spicy at all! The Peruvian group I was with was worried I wouldn’t like the dish because of its ‘spice’, but funnily enough, Peruvian “spicy” food is actually quite mild. Regardless of the spice level I thought the meal was delicious! Here is a link to a recipe I found for the potatoes online: puca picante.

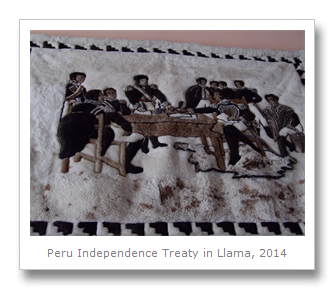

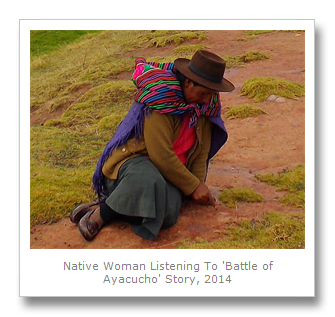

The December 1824 Battle of Ayacucho was a decisive event in Peru’s attempt for independence. On the pampas in front of us was a bloody battle between the Royalists and the Independents, each about 9,000 troops in number. Our guide pointed to Kunturkunka or the “condor mountains,” explaining that Spanish records wrote that the royalists hid in these mountains for days before running out of supplies. When they came down from the mountains they met the independence fighters, led by General Sucre, on the pampas we were standing on, in a bloody clash. Sucre’s troops included Europeans – and the statues on the memorial on the battleground has representations of British soldiers, as well as other Europeans and Peruvians involved in the conflict.

As our tour was returning back into town, the tour guide told me about a bakery which made special breads local to the region of Ayacucho called chaplas. I approached the bakery and got to watch how the bread was made before buying a couple of pieces to try. Quite tasty, especially the chaplas flavored with anise seeds. I also tried some larger, shinier bread called wawa. Interestingly, the word “wawa” means baby in Quechua, which obviously comes from the noises babies make. My guide, who led me to the bakery, explained that the special wawa bread is typically only made on All Saints Day. Online I read that these breads were made as a “…consolation" for those who had become pregnant nine months earlier during Carnaval.” (Ayacucho Food Blog)

When I returned from the tour I had some time to kill before my overnight bus back to Lima. I decided to have a couple slices of pizza and some chocolate cake (yes, calorie splurge!) at a nearby pizza place. Once I had exhausted their WIFI, I headed to the bus station and got settled into my chair. Back to Lima and to see Colin - who was waiting with flowers.

Glad to be back!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment