There are several options when traveling from the colonial city of Cusco to the city of Puno located high on the Peruvian altiplano, next to Lake Titicaca. We decided on taking one of the tourist buses which we booked online. There were several choices, all of which shared the same itinerary, and all of which were infinitely more welcome than the stinky and cramped buses we were used to in Bolivia.

We settled on the Wonder Peru bus as it was slightly cheaper than the other options, even though the itineraries were the same. We booked the bus and were emailed an e-ticket which was a welcome change to having to organize everything at a bus stop in the middle of the street. Things here are so much easier than in Bolivia or Chile, two countries that have some of the worst tourist infrastructures in South America.

The owners of the apartment we had been renting in Cusco were coming back the day before our bus was due to leave, so we went and stayed in the excellent La Casa de Ali Guest House just outside the center of Cusco. The next morning, we jumped in a taxi, early, to catch our bus for 7am. The bus itself was pretty comfortable as it was seated passengers only, and we noticed only foreign tourists on it.

The draw of using these tourist buses is that on the way between destinations they stop at various points of interest. First up was a church we had already visited on one of our day trips around Cusco called La Iglesia De Andahuaylillas. Francesca has already written about this church, but it was nice to see the 400 year old pisonay trees in the town’s plaza again.

We spent about half an hour at the church before re-boarding the bus and heading further into the Sacred Valley of the Incas. This tourist route is called the ruta del sol, or route of the sun, as it follows the ruins of the Incan Empire stretching out to the South towards Argentina. The route soon left the Southern part of the Sacred Valley behind as we shot past the turnings to the East that led to the Amazon rainforest, and we continued South into the Vilcanota Valley. This valley held the Aymara-named Willkanuta river (known as Vilcanota to the Spanish), which, downstream became the Quechuan Urubamba or sacred river. This river flows all of the way North past Machu Picchu and feeds into the Amazon River itself.

We passed several beautiful natural lakes, a couple more colonial churches, and a statue of the last Incan leader, Tupac Amaru. After an hour or two we came to our second stop of five, which was a ruined Incan religious, military and astrological center called Raqch'i. We had not seen this site advertised at any of the tourist agencies in Cusco, and yet the number of visitors have increased from only 452 in 1996, to over 83,000 in 2006. This growing industry in the region has allowed for some outstanding restoration work and maintenance which will hopefully preserve at least some of the site for future generations. Hopefully some of the local governments in Bolivia and Chile will see this and try to cultivate the same results before they lose their ancient archaeological sites – presumably the tourist buses themselves should be invested in by those governments.

Raqch'I is known as the Temple of Wiracocha, who was the Incan supreme deity. All around the site we could see an Incan irrigation system that was in fact still in use for the more modern farmers who still used the terraces of the Incans to grow their crops. The largest structure, which was also our first stop, was one of the biggest temples left standing in South America. At around 100 by 25 meters, the temple was a monument to Wiracocha, the Incan creator god. With most of the temple now gone, it was still impressive to see some of the adobe walls standing after hundreds of years, including the bases of two rows of eleven columns which would have supported the roof.

Little tiled roofs placed on top of the temple walls protected them from the weather, placed there with restoration money provided by the French government and much-needed tourist dollars. We noticed, however, that nesting birds have pecked their way through the walls creating holes and, in turn, cracks, which led us to speculate that the walls might not last much longer. At up to 20 meters in height the weight of the walls might eventually be too much, especially if a big earthquake hits.

Our guide pointed out the surrounding 7 kilometers of Incan walls that had defended the site. They had built a moat also, and the natural topography of the environment suggests this was an important site that needed protection. This probably had something to do with the approximately 200 or more circular storage qullqas, which were probably used to keep grains and other crops throughout the year. They were all neatly grouped in rows with all of the doors facing the same way. Maybe they were circular so that they could be cleaned more easily than the other square buildings, or maybe for better ventilation for the produce inside.

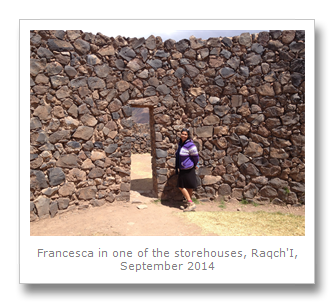

The final sector we saw was the accommodation area. Houses surrounded the various plazas and possibly held around 300 people. Priests and administrators almost certainly lived in these houses, with the travelers who passed through apparently staying in the storage houses.

The houses were of a different architectural style than the temple – all Incan temples having been built in the Imperial Style. This style has straight lines and stones that fit together so perfectly that you cannot put a credit card between them! The houses and storage units were of a more basic style, with uncut stones and adobe used as walls.

The site could have been a resting place, or tambo, for travelers heading South to Argentina. The Inca trail leading there makes up some of the 5200 miles of the roadways and trails used by messengers and travelers. The Incans maybe even used these sites as checkpoints to control movement in their territories.

Listening to the different guides on the various tours we have had, and seeing the explanations in the museums in Incan territory, we have come to realize that no-one really knows the truth about the Incans and their way of life. Our knowledge is solely derived from the biased Spanish accounts from colonial times and from the way people live today. As the Incans and pre-Incan civilizations did not have any written history, there is much conflicting speculation about their religious beliefs and culture. You just have to take all explanations with a pinch of salt and decide for yourself.

After some nice photos, it was back to the bus, and time for a buffet lunch at a place called Sicuani. These buffet places were always pretty good and plentiful. We had lots of salad, meat, potatoes and even desserts. We loaded up and washed it down with some nice mint tea.

Back on the road again, and we were heading further and further South. We had left the valley and had continued upwards in altitude until we had come to the zenith of this particular journey. At 4335 meters above sea level, the La Reya pass has views of the surrounding snow-capped mountains and volcanoes. It is from the La Reya mountain range that the spring waters come from that fill the sacred river valleys that end up in the Amazon river. We could even see vicuña frolicking in the distance.

Our next and penultimate stop was a town called Pukara, which means fortress in Aymara and Quechuan. The Pukara culture (800BC to 500AD) was a pre-Incan civilization related to the famous Chavin culture from the North. These cultures were both the forerunners of the more famous Wari and Tiwanaku cultures, later overrun by the Incans. The ruins at this site now actually overlook the city called Pukara, which was built by the Spanish after they ransacked the native city they found there. Brick by brick, they symbolically and literally dismantled all of the temples and built a church with the desecrated ruins – this was an orchestrated campaign called the ‘extirpation of idolatries’.

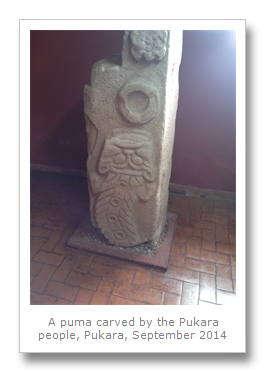

The ruins, called Kalassaya, are essentially a group of semi-underground pyramids and burial mounds. The classic farm terraces surround the temples which were all used for ceremonies. The temples were built long before the Incans ever existed – around 500BC. It was an American archaeologist called Alfred Kidder who uncovered the many ceramics and mummies found at the temples. Pukara town itself now holds these artifacts in the local museum. Many statues show warriors with the decapitated heads of the Pukaran’s enemies. Pumas, condors and snakes also figured heavily in the pre-Incan cultures, showing how the Incans based their spiritual and societal beliefs on the cultures that came before, much like Christianity has borrowed and stolen from the cultures that the Romans conquered. In fact, Pukara means fortress in Quechuan, and has come to be the name for numerous ruins in South America. Even Kalassaya itself is a recycled phrase meaning ‘standing stones’. We do not know what these cultures even called themselves, and so the names we do have for them are arbitrary.

These cultures had many things in common though, including an obsessive infatuation with the natural world around them. We visited the museum in the town of Pukara, and my favorite statue was one, seemingly, of a catfish, which used to live the surrounding rivers and lakes. Nowadays, all of the trout introduced from Europe have pretty much taken over.

We learnt about how almost all of the statues found at the ruins contained images of severed heads. Human sacrifice was a big thing back then, as was collecting the severed head of your enemy as a trophy. Owning a trophy head bought good luck in many aspects of life, including fertility, harvesting and hunting. In fact, Hatun Naqak is a big figure often represented in Pukara stonework. He was also known as the Great Decapitator.

We also learnt how the Spanish had deliberately defaced or broken these statues, and how the archaeologists used meticulous colonial records to determine where the Spanish had found each piece, and what they had done to them, even the pieces that seem to represent the natural world.

All of the rivers North of the La Raya pass eventually ended up in the Amazon, and therefore the Atlantic. But all of the rivers South went to Lake Titicaca, which we had seen when we crossed over from Bolivia a few months before. We arrived at the Lake again, this time in Peru, leaving our bus journey behind, we made our way to our hotel in the city of Puno.

The next day we relaxed a little after this epic bus journey, and then in the afternoon we did a day trip to a local attraction called Sillustani. We booked the trip through our hotel Huaytusive Inn, which is a definite recommend for anyone staying in Puno. This site holds some ruins I was pretty excited to see – some huge funerary towers called chullpas. These towers are between 3 and 12 meters high, and held up to 35 bodies in each one. It is speculated that social class and standing told of what height your funeral tower would be. All of the towers faced East and had domes, and most of them were destroyed, not just by grave robbers, but by Earthquakes.

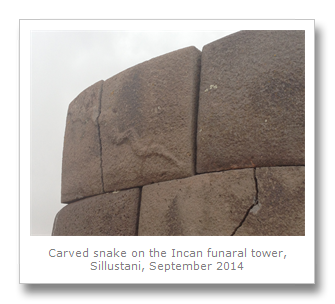

The really interesting aspects of the towers were the external carvings of pumas, lizards and snakes, and the unfinished towers that the Incans left once they took over the site from the Quolla people (1100AD to 1450AD), and assumed the same funerary rites their predecessors did. The Incan stonework was evident in the later towers, and had a much more polished look than the older ones. There was even a ramp left over from Incan times, next to one of the towers, showing how they would build the towers by pulling/pushing the stones up it to the top layer. These stones were all farmed from quarries around the site.

Ancestor worship was prevalent in all ancient cultures, as was a healthy respect for nature. The Incans and other pre-Hispanic cultures all had a unique perspective on this though. Evidence suggests that they believed in three levels of spirituality: the underground, or afterlife, which was symbolized by the snake. Snakes were associated with water, as the rivers snaked down from the mountains. The puma represents the living plane and also signified adaptability, as the cat lives in all environments, from the coast to the Andes and in the jungle. The higher, spiritual plane, was represented by the condor. When you died, the condor would be the carrier of the soul to the underworld (they eat bodies). These central beliefs seemed to endure from pre-Incan civilizations through to even modern Andean belief systems.

We got about 45 minutes to walk around the site, where we got to view many of the towers and the view of the nearby Lake Umayo. A huge thunder storm started as we walked around giving the site an eerie feel, and also a scary one. One of the towers was actually destroyed by a lightning strike. Twice!

After we finished walking around we had a surprise visit to a local farmer’s house. The visit seemed a little contrived, and it did not seem like the local people really lived there. They did make us some interesting food though, which was awesome. Some boiled potatoes with some liquid salted clay, which looked unspeakable but tasted great. The brown clay was supposed to be filled with vitamins, good for digestion. Also there was home-baked bread and cheese. Lovely.

We made it back to Puno without getting wet, which was real lucky. We could see the whole of the altiplano or high plains stretching out before us. This plateau goes all the way down through the West of Bolivia to the North of Argentina (both of which we had visited). We headed back to Puno which we were going to explore the next day.

Puno was established in the 17th Century, and relies on agriculture for it’s livelihood, and smuggled goods from Bolivia for it’s practical needs. Tourism is booming all along the routes of South Peru, and we headed out on the 6th September to visit some of the local attractions.

First up was the Museo Carlos Dreyer, named for a German painter who settled in the town in the early 20th Century. Dreyer dedicated himself to painting the Andean people and exhibiting the paintings all over South America. His family left these paintings to the municipality of Puno and the museum, which now holds antiquities found in the archaeological sites around the town.

Polychromatic ceramics from the nearby Nazca region (and culture) were on display, as were lithic objects including a lizard with three tails carved onto one of them. Yupanas, which were Incan stone calculators, were also shown, which some researchers believe were based on the Fibonacci number series.

The main attraction at the museum was the gold objects and mummies found at Sillustani. A bone flute and various paintings of Sillustani were stand-outs. There was even a weird German typewriter that Dreyer used to own, that Tom Hanks would probably cut his right arm off for.

We left the museum and briefly visited the cathedral and the artisanal casa del corregidor. We jumped in a taxi down to the lake itself – which is never written about without being described as ‘the highest navigable lake in the world’ – an overblown honor if you ask me. Lake Titicaca is quite pretty though, and people have been enjoying it forever.

In 1861 the Peruvians commissioned a British company to provide them with some iron-hulled boats to protect their claims of the lake over the Bolivians. The boats Yavari and the Yapura were delivered in pieces, around Cape Horn, to Arica in Chile, which we had also visited! These pieces were carried (all 2766 pieces of them) by mule across the Andes, and reassembled on the lake, and the ships made their maiden voyages in 1870.

As oil and petrol were scarce so far and so high up from any where civilized, they used to use llama dung to fuel the boats. That was until 1914 when a spare engine was installed. The boat we visited, the Yavari, has passed through many lifetimes, as mail carrier, Bolivian repellant, floating hospital and plain old passenger ferry. Even Prince Phillip had travelled on it and wrote the owners a nice letter, which is displayed on the boat since they restored it in the 1980’s.

We wondered around, but if you have toured any kind of historic ship before, this one is probably a miss. At least until they start sailing it again. As a museum, it was not particularly interesting. In fact, the numerous birds of Lake Titicaca were the attraction, including the awesome Andean Duck, with its bright blue bill.

That afternoon, we headed to a Peruvian favorite, a chifa. This is essentially a Chinese restaurant - a kind of Peruvian/Chinese fusion. We had sweet and sour lemon chicken with fried rice, and a pork dish too. Delicious.

We had planned on going on a boat tour the next day, but unfortunately we both got sick the next day (chifa, anyone?). We laid up for two days, then got back on track with our boat trip. This was our second trip through our hotel, and was another trip that my parents had been on a few years before! From the sound of things though, it was a lot less touristy back then.

The famous floating islands of Lake Titicaca used to be a few reed islands which housed the Uros people, but nowadays most of these peoples are of mixed Aymaran and Uros blood. The Uros language itself died out over 500 years ago when the Incans conquered the people of this area and made enslaved them.

We passed the stinking filth of the bay in which Puno blasts out it’s sewage, and it was not hard to see how much tourism is damaging this area. Our guide even pointed out new multi-story building being built that were making the skyline even more unpleasant (difficult for South America with all of it’s cables hanging everywhere). We did see some birds floating about here and there, but as we had left alongside at least a dozen other boats that morning, it was not easy to spot them up close. In fact, there are several endangered animals including the Titicaca Frog that quite possibly will be extinct soon because of human activity on the lake.

We arrived at one of the floating islands, which are now more of an inter-connected floating city, complete with churches, metal buildings and satellite dishes, and we disembarked. The islands are now one huge tourist trap, but they do give a good and informative presentation on some of the traditional practices there. They talked to us about how they built the islands – essentially by farming the totora reeds around them. The roots of these reeds are a floating amalgamation of dirt and mud, which the Uros harvest and then leave out to dry. These are pierced with stakes which are tied together, and then anchored to the bottom of the lake to keep the islands from floating away. Once the foundations are in place the reeds themselves are then laid down in a criss-cross style and left to dry out. These reeds are laid down over time until they are effective platforms to live on. We found them bouncy to walk on, and also quite damp, but the Uros’ buildings are further elevated by a mound of reeds placed underneath them so that they do not sleep near the water level. Even the cooking fire is placed upon a large stone so that it does not burn the reeds.

The rest of the time was spent walking around and trying to work out how many of the people actually lived on the islands – we had heard a range of estimates from 40%-80%. It looked much more likely that the people lived on the mainland and took turns to come out and entertain the tourists. We think it would be much better to skip this obvious fallacy and just show the tourists how the people used to live – maybe with a little role play (men dong the island building and fishing, and women the weaving, and then swapping roles, etc.). It looks like the pretense that this traditional way of life is still maintained is pretty ingrained though, so don’t expect anything to change in this region.

At this point there was a crossing of the lake to another island, and everyone was herded onto a Uros Dragon Boat – made of reeds of course. We avoided this unnecessary extra expense and travelled on the boat we had arrived in instead. The ride in the Dragon Boat was for all of ten minutes, so did not look worth the money, even if it was only for a few dollars. Be careful when you get to the next island as they have hidden expenses! It is essentially just a floating tourist café, and the lack of prices on the teas, coffees and even the stamp that they use to stamp your passport, are so they an charge you unexpectedly after the fact. Annoying.

We had opted for the full day trip to go see the island of Taquile after the floating islands. Personally, I thought the Isla del Sol, or Island Of The Sun, in Bolivia was much more aesthetically pleasing and worthwhile. Walking to the top of Taquile was a bit of a struggle at this altitude, but the views over to Bolivia’s Cordillera Occidental were pretty good. The town was quite pretty with some crumbly modern buildings that were so poorly constructed they looked colonial, even though they were far more recent.

We had some Peruvian lunch which consisted of trout, potatoes and rice. Trout is an introduced species to the lake, and since we found out about the awful pollution in Lake Titicaca we have not eaten it since. The reeds that are now used by the Uros people to build their islands are supposed to be what stops the pollution from Puno running into the lake, but as there are many more communities all around the lake, all polluting it as well, avoiding eating the trout from the lake may have been the better option in hindsight. In future, with the reeds disappearing, there will not even be that barrier between Puno’s pollution, and the fish on your plate in places like Taquile.

There were many more tourists on Taquile than the Isla del Sol, and so it was harder to enjoy it for that reason. We quickly walked ahead of our group and guide, and got back to the boat first. It was nice to spend the time together, and we were glad when we made it back to land some three hours later.

That evening we decided to check out the Balcones De Puno folk show. We just turned up and got a table at the front, so possibly no need to book ahead. The food was a little expensive, but it was good, as were the musicians playing. This band had two guys playing panpipes who were leading the music, which is unusual as we are used to the guitar being the lead in most places we had been to in the Andes. Some seem to think the place is pretty contrived on TripAdvisor, and I guess that is fair, but it is a tourist folk show, so what did you expect when you went in?

Our last day in Puno consisted of us heading out ourselves to see some of the outlying attractions back towards Bolivia. Buses to Juli run from the Southern Terminal of Puno, and our route was a bit more convoluted than it should have been.

We first got to a village called Chucuito, which is only about half hour away from Puno (although road works can increase this journey time). We visited the overly-priced but interesting fertility temple of Inca Uyo first, which is a fenced-off square that holds a very modest temple, in size only. Immodest due to the statues of penises inside, one even about one meter high! Those dirty Incans!

However, some people are disputing whether these statues are what the locals claim that they are. Similar ‘statues’ exist at other sites, even Machu Picchu, which show them not as statues at all, but rivets which fit into reciprocally shaped stones to help hold roofs and walls together – a different type of joint altogether! Apparently the stones were found in a storage shed and put together to look like a fertility temple. Whatever the truth is, they are definitely carved stones from hundreds of years ago, sourced from local quarries, probably by the Incans.

After the ‘temple’, we walked up the hill to the university’s trout farm. We found this the most worthwhile visit of the day, as they had the wonderful Lake Titicaca water frog there! They are breeding the frogs, trout and even some salamander, and, as the weather was really nice, we enjoyed it immensely. A very pretty setting, you can wonder around for a dollar or so each. Hopefully they can get the frog back on track in it’s natural environment.

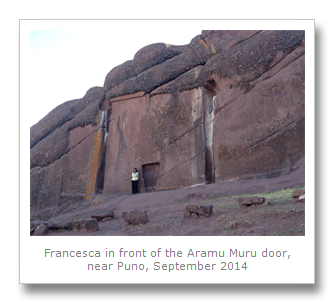

Our last stop, via was to visit the Aramu Muru door, which was located near to the last town that the bus visits, called Juli. We had all sorts of problems trying to get a bus from Chucuito, and so had to double-back to Puno first. As this is the case, I recommend going to the door first, early morning, and then visiting Chucuito on the way back.

Known locally by different names, including the devil’s doorway, gateway of the gods and the Peruvian stargate, this carved alcove is located about 2 kilometers walk from the main road just outside Juli. Nonsense legends of people disappearing through the doorway, and of an Incan golden disc that was placed in the alcove to open it many centuries ago were probably made up quite recently. Like the ‘fertility temple’ there is a charge to enter the area of Aramu Muru, by locals looking for some pocket money.

The site clearly looks like an abandoned construction project, and the doorway, which faces East, matches the ones at Sillustani. My guess is an abandoned tomb project. My favorite part of this area was walking past the door and up into the area known locally as the ‘stone forest’. We saw a huge rabbit or hare, some buff-necked ibis, and some great views over Lake Titicaca.

A strange but full day, we got back to Puno, and we had decided that the next day we would utilize another tourist bus from the company 4M. In hindsight we would probably have used a local bus, but it got us on our way to Arequipa nonetheless.

No comments:

Post a Comment