Bolivia’s fourth largest city was a move back up towards the high Andes for us after spending so long in the Eastern lowlands around Santa Cruz. At 2558 meters above sea level, Cochabamba was also known as The Garden City due to its year-round clement weather. We were on a bit of a deadline to see the last cities in Bolivia because we had to get to the Inca Trail in Peru within the next month! However, we found time to fit in the things that we wanted to see.

We asked at the Cochabamba tourist information office about the two nearby National Parks we wanted to see, and we were encouraged to make the journeys independently of a tour agency, and make the trips ourselves. We found this to be pretty good advice.

We next went to the Santa Teresa Convent, but they told us they only had English tours later in the day. They refused to give us a discount for having no English speaking guides available, and it was quite expensive, so we agreed with them to come back at 4pm. We then tried the Portales Palace which was across town so we tried to take a taxi. Three taxi drivers had no idea where the palace was, even though it is now a cultural center and a major tourist attraction. This was our first red flag that actually, Cochabamba was far from the tourist trail, and not many people bother going there.

We eventually got to the palace, which was built by Simon Patiño, a wealthy mining magnate who rose from poverty to riches quite by accident. He worked as a debt collector for a mining store, and decided to settle a debt for a piece of land on the side of a mountain. He was fired for this piece of individualistic thinking, and forced to pay back the debt himself. He acquired the land, and quite by accident discovered large deposits of tin there. When he died in 1947 he was one of the fifth richest men in the world.

Unfortunately, the opening hours were all wrong online, as is often the case in South America where websites are rarely kept updated, if working at all. The palace was closed, so we headed back into town.

We found one museum that was open; the anthropology museum. Split into different sections, from pre-history, through the different cultures in the region, there were some really interesting pieces there. My favorite was some Jesuit papers that showed how they used a language created with stick figures (as the indigenous did not have written language) to teach the natives the stories from the bible.

After learning about how the agricultural indigenous were replaced by the more administrative and warlike Incans, our semi-disappointing day took a turn for the worse.

We had some lunch and headed down to Cochabamba’s famous marketplace. We had a big shopping list, and this huge sprawling market was supposed to be able to cater to all needs. This was our second big disappointment of the day, as about ten minutes after we arrived, a dirty Bolivian thief spat on the back of my head! This is a known tactic we had read about, and as I turned around, distracted, three men began to surround me. I knew what was coming, but the men did not. Francesca bowled into them like a bowling ball, and they all disappeared quickly down prearranged routes of escape. I noticed the market sellers were looking on in amusement at a scene I think they have seen play out a hundred times. I think they are colluding with the criminals in that case, and are no better than they are. Scumbags.

La Cancha Market is definitely NOT safe – DO NOT GO THERE! Francesca’s heroic efforts probably ensured I did not get a knife pulled on me, which is apparently what normally happens. We got out of the market, quickly and directly, and never went back. The would-be muggers did not succeed in getting anything, mostly because they did not recognize that we were together and so did not see Francesca watching all of their moves like a hawk! That is why she is my hero, and everyone should admire her courage and bravery. Thanks baby x.

After that near disaster, which could have been a lot worse, we walked down to a nearby local artistic center. The walk was very nervy, as the Southern part of Cochabamba is not a recommended place to be, especially after a near-mugging. When we arrived, we wanted to just walk around, but were told to wait for the director. We waited for ten minutes, but we realized that it was time to head back to the convent for our tour, and the art center looked pretty bleak and uninteresting anyway. I think the reason they have you guided round is to solicit money from you at the end, which would have been a waste of everyone’s time.

We got back to the convent, with the taxi driver having no idea where it was. Every other car in Cocha is a taxi, and I think the country boys come to the city to make money as a driver, but have no idea where anything is at all. I showed the tax driver where the huge, un-missable convent was, and we went inside.

The woman who had told us to come back at 4pm now told us that they did not have an English speaking tour that day. Huh? This day just gets better! Francesca and I argued with the two girls there in vain, as 1) they are not used to people complaining and so did not know what to do, 2) where stupid and so did not know what to do. We left, advising them not to tell lies in the future. We never got to see the convent.

We then spent all of the rest of the day trying to book a tour for Francesca to go see the Aymara New Year festival. We visited one agency, whose website gives a wrong address. A kind man in a bookshop called them for us, and they told us they were located somewhere else. We went there, and they had literally no useful information. They told us one thing, then another, then something different from that. We walked out. Not ones to give up however, we got Francesca booked on a tour, and went back to our hotel – just another day in South America! But we survived with everything intact.

After showering the spit out of my hair (gross), we got our stuff together to go and visit one of the National Parks the very next day, because that is how we roll in the face of adversity. We were glad to be temporarily leaving Cochabamba, leaving the slightly disturbing, puffy-faced, out-of-it glue-sniffing kids (still so common in the streets of Cochabamba despite the online literature saying this is in the past) behind.

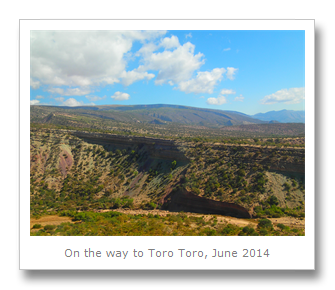

Success at last! We managed to get a trufi (shared minivan taxi) from Cochabamba to a village about 4 hours East called Toro Toro. The Toro Toro National Park is a lovely gem in Bolivia that demands about 3 days attention, which is what it got from us.

We arrived, with our fellow passengers, at the plaza, and immediately found a hotel. The rules are that you first register and pay for a five day pass, and so we did that, and then we engaged a local obligatory guide (the tourist information lady as there was no-one else at the time) to do a nice afternoon trek.

Set amid beautiful mountainous canyons with colors of red, green, and browns, Toro Toro is a really nice park to walk around and do some hiking. The landscape has been molded geologically since the Cretaceous period, with some of the land having shifted to an almost vertical position, creating really interesting formations. Much of it is covered in sparse vegetation, and the weather is mostly hot and dry.

You can choose which of the several treks you want to do, and we chose to visit El Vergel, which was a half day hike to a waterfall in a canyon, and back. Our first stop, though, was at a set of sauropod footprints, left millions of years before by a huge dinosaur. The guide tried explaining to the group how two of the footprints were actually one print, and so I had to correct her, and explain how dinosaurs walk – like elephants! Unfortunately, my learned wisdom fell on deaf ears, as the rest of the group decided not to believe Francesca and I, instead believing the clearly untrained guide, once again proving the Milgram experiment does work.

We even saw three-toed carnivore footprints, left by a medium sized dinosaur. I always love to see dinoprints, and Toro Toro has many more!

A walk down a dried up riverbed was very pleasant, and I was keeping an eye out for snakes, but did not see one. We did pass some local farmers who were using their donkeys to pound some wheat into submission though.

Soon we came to some drops in the riverbed. Old waterfalls that only flow in the rainy season. They had left their mark in the shape of some natural stone bridges that some of the group stood on. They did not look too safe to me, so I gave it a miss. In fact, after the girls in our group moved off of the bridge, I noticed it had been propped up, not so naturally, with bricks.

Bromeliads and cacti were everywhere, and we finally came upon the Toro Toro valley which had some incredible views. Large birds of prey were circling, as were the occasional parrots. This National Park is home to some endemic Macaws which do not exist anyplace else, too! I hoped to see those later.

A narrow and fairly steep set of steps led down to the canyon, over 300 in all. It was worth the descent though. Pretty flowers, clear pools of water and some huge rocks made for excellent scenery. We finally made our way down further along the canyon riverbed to a wonderful set of waterfalls. It is a magical place and a great way to spend an afternoon.

We made our way back, carefully, over slippery rocks. I could see why a guide was necessary, as, when it got dark, it would be impossible to get out of this canyon. Luckily, we all made it back safely, and we made plans to meet in the morning, to engage another guide to visit the further flung reaches of the park.

At 7am, we got together with the same girls we had travelled with, and a Bolivian couple (who later really infuriated me by dropping litter on the floor in the park – arghhh!). This was an all-day tour to Itas City and the Cave of Umajalanta. Itas was a collection of rock formations, caves and different gullies and canyons to hike through. It was located much higher than the rest of the park, at about 3500 meters above sea level, but unfortunately it was a drizzling and dreary day so we did not get to see much – and it was freezing.

There were some cool rock paintings we saw, and walking through the labyrinth of trails was nice exercise. I did like some of the cave formations we passed through, though. We had had to take a car to the ‘city’, and so we took the same car back to the trail leading to the entrance to the Umajalanta Cave.

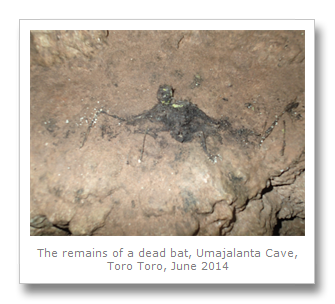

This cave is a bit of a workout, with big drops, holes and rubble everywhere. That and the toxic water found inside, and you have to be pretty careful. The cave is over 4600 meters and 164 meters deep, but a lot of it has still not been explored, as it is underwater. It is possible to go diving in the cave, but our trip was spending about 3 hours walking around a big loop.

There were some slides we had to use ropes to go down, some very narrow parts that we had to squeeze to get through, and at the end, even a small lagoon which had some endemic blind fish that we saw! Another awesome experience in Toro Toro. I liked the different rock formations and stalactites and stalagmites – and the guide showed us a part of the cave which was unfortunately covered in graffiti from the days when the locals used the cave to party in.

On our way back to the car, we saw even more dinosaur footprints of the carnivorous theropod variety. The next day, Francesca and I found our very own guide and headed off on a nice walk up to a mountaintop trail called siete vueltas. This means seven turns, referring to the trail itself, but it only takes an hour or so to get up there. Once at the top, we saw millions upon millions of small fossils, all from a time before the tectonic plates forced the land up way above sea level. These fossils were mostly shells made up of brachiopods, cephalopods and other such small marine animals. There were so many fossils all around us, everywhere, and it was our first time really fossil-hunting successfully. Of course, you are not allowed to remove any, but it is cool sifting through so many cool fossils whilst overlooking the town and valley far below.

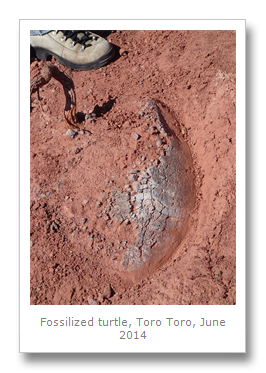

It was such a good morning, we asked our guide to take us to another fossil zone, called the Turtle Cemetery. This involved hiring another car, which we did, and we set off to see a relatively new attraction for the park. The park is owned by the people who live there, as is often the case in Bolivia. The guides are just local people who were born in the area, into that career – they have no special training – only what they learn from books or each other. That is why the guide got the footprints wrong, I realized. They charge fees for visitors to see the land, and make it obligatory to take a guide so that the people benefit economically. It is an industry. One which I fully support as they must look after the land and it’s important findings, or suffer from a lack of tourist income. The turtle cemetery was long known about by the locals, but it took them some time before they realized that people would be interested in it as well, so it is a relatively new attraction – which made me wonder what else is out there!

A museum with some interesting geological history was added by scientists here, and we also watched a movie our guide put on about the dinosaurs. We watched it, and then we went inside a fenced off area that was full of hilly sand dunes and rocky areas where they had found several turtles’ shell fossils. The ones that were exposed were now starting to wear down and fade, and even break up. There are probably many more, but quite rightfully, the people are leaving them be until a way can be found to show them without damaging them.

The different colored rocks and landscape were astounding in this part of the park, but we decided we would leave, and head back to town as we had one more part we wanted to see.

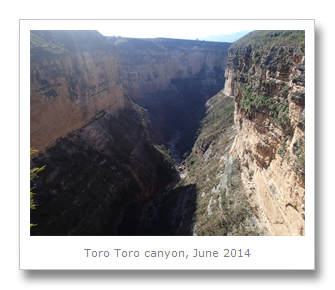

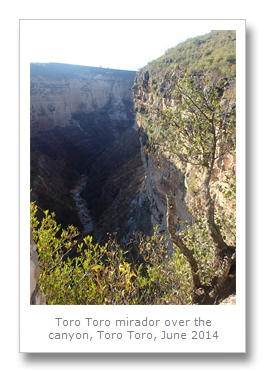

We got back to the town just in time to walk back out towards the viewpoint, or mirador, over the Toro Toro canyon. It was around 4.30pm and we waited at the viewpoint which was about 300 meters over the canyon with a walkway that jutted out over it. The reason for our wait? The rare Red-fronted Macaws that were endemic to the region. We heard there were only about 2000 living in this region, and although they have been bred in captivity successfully, this was the only place you can see them in the wild.

We waited for about an hour, and I started to think we would never see them, but at 5.30pm, almost on the dot, they started flying back to their nests in the cliff faces below, and the trees even further below. They all flew in pairs, as Macaws are monogamous and mate for life. They were magnificent in flight, with the blues, greens, yellows and the red part on top of their heads flashing through the sky!

Toro Toro was an excellent experience, one of my favorite National Parks, with lots of variety and interest! The cave was a bit difficult, but we saw people much older (and bigger) than us get through OK. On our last day, the 20th June, we even managed to fit in the museum in town, which is pretty much a showcase of the many different fossils found at siete vueltas but displayed artistically as lots of different shapes and dioramas.

We headed back to Cochabamba, and found a relatively cheap hotel to stay in, and on the 21st June, Francesca went to an Aymara New Year festival which celebrates the solstice.

Once she came back, we had no time to waste, so we headed off to the other National Park we wanted to visit. A bus out to Villa Tunari took around five hours (almost every bus in Bolivia contains really smelly people), and when we jumped out, we found ourselves firmly in jungle territory again. Humid and full of bugs, it was pretty dark when we arrived, so we grabbed some food and went to bed in a hotel next to the Espiritu Santu River, which eventually flows into the Amazon river.

The next day we found a taxi to take us down to the entrance of Carrasco National Park. The town and the National Park are both in the region of Chapare, which is renowned for being amongst the poorest and most dangerous regions in Bolivia, particularly for people and animal trafficking, child abuse, and illegal coca growing.

On our way in, we had seen numerous big lorries carrying timber out of the jungle, and covered loads which we assumed were coca leaves. We even saw people getting on the bus with big bags of coca leaves, all of which added up to huge deforestation, which we also saw first hand too.

Our first foray into the park was relatively successful, when we went to visit the guacharos, or oilbirds that live there. Unfortunately, no one bothered to tell us that the birds fly North for the Winter (between June and August), and meet up with the other oilbirds that are from Venezuela, Columbia, Trinidad and elsewhere. Of course they do not advertise this, primarily so tourists still turn up at the National Park, even out of season. We were a little disappointed but the trail to the oilbird cave was pretty interesting anyway, and we were shown all manner of plants and trees, including ones with spikes on the trunk to stop monkeys climbing it, and others with toxic sap that could make a person very ill if they even touch it!

The trail began by crossing a wide river on a pulley system, and lasted a few hours. We saw some giant ferns, palms and bamboo trees. There was a house located in the park, to our surprise, and they had some really aggressive dogs which really should not be allowed in a National Park. We realized straight away that the chance for seeing animals here would be zero. My favorite tree we saw was the walking palm, which basically grows new roots down to the floor, and loses the old roots, and therefore seems to be ‘walking’ across the jungle floor.

We did see a huge bullet ant, an ant with an extremely poisonous bite. It is called a bullet ant, because it’s bite feels like being shot. Some locals call it the 24 hour ant, because the pain lasts that long! We made sure we stayed well away – especially because when we directed the camera lens at it, it simply reared up and got all aggressive.

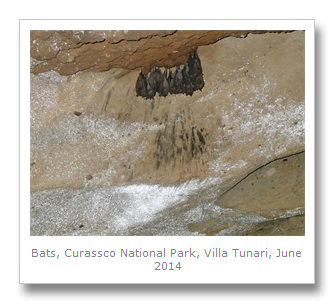

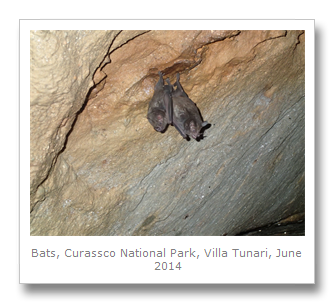

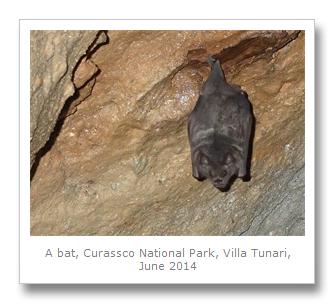

We came to a set of caves, all of which were only discovered in 1942 when they heard the sound of the oilbirds coming from within. We entered the first cave, and we saw some awesome silky short-tailed bats all clustered together hanging from the roofs right near our heads! We ventured inside and got some nice photos of them.

Outside again, and we saw some little tadpoles in a small puddle. The last stop was the oilbirds cave itself, and we were hoping to see one, as sometimes there are a few left behind that have not learnt to migrate yet. I saw lots of seeds on the cave floor, and the guide and Francesca said they saw some eyes shining at the back of the cave in the torchlight, but I did not see any of the birds. Guess we will have to wait until Venezuela where the majority of them live. The birds are called oilbirds because they used to be captured by the locals and boiled to death down into an oil! These nocturnal birds are special because they are the only nocturnal fruit-eating birds that fly, and they navigate by echolocation, much like bats! Luckily they are now protected in Carrasco, but with the onslaught of people encroaching into this park, and the governments complete lack of concern for the environment, I wonder how much longer the birds will come to this particular cave.

We had made plans with the guides for them to take us on a few more hikes either later that day or the next, but the guides were really useless and lazy – they are never at their posts and never answer their phones. My recommendation is to not go out of your way to go to Villa Tunari because a lot of the things you can see there, like giant ferns, oilbirds and the cock of the rock bird, can be seen elsewhere, in more reliable and accessible places.

We headed back to Cocha the next day, and pretty much left straight away to go to La Paz, the capital. Cochabamba is a very poor, very dangerous region, so be careful if you go there, and make sure you are not on a deadline and have plenty of time, because the people who are paid to run the tourist attractions rarely show up and hardly ever give out the correct information.

No comments:

Post a Comment