June 21st is the Aymara New Year, which I decided to attend. The Aymara are one of the 38 ethnic groups that make up Bolivia, and the current president of Bolivia, Evo Morales, is said to be part Aymara himself. The Aymara people make up more than 25% of Bolivia’s population, and in more recent years they have been gaining more political power – part of the reason their new year celebration has been declared a national holiday. One of the notable historic skills acquired by the Aymara people is their knowledge of astrology, and June 21st is celebrated because it marks the Southern Hemisphere’s winter solstice, when the sun is at it’s furthest point from the the equator. On that day the harvest period ends and a new agricultural cycle begins. This makes June 21st simultaneously the shortest day and longest night of the year in this part of the world.

The tradition holds that the night before the sun rise the Aymara people get together and hold a vigil throughout the night, keeping themselves awake until the sun’s first rays rise above the ruins or the mountain where the celebration is taking place. Therefore, on the evening of June 20th I got into a minibus along with a group of a dozen or so other people and started the 4 hour drive (130 kilometers east of Cochabamba) to the ancient ruins of Inkallajta.

The ruin of Inkallajta was one of the last places of Inca military expansion towards the east of Bolivia. While there are many clearly Incan structures present (there are typically Incan niches in the Kayarani or main building) there was also a pre-Incan astronomical observatory at the site indicating that the Incans were not the first people to establish themselves in this area, and that it was indeed a takeover from a previous culture. But more about the ruins in the morning when we have some light! Back to that evening…

Once we arrived at the festival, we got our blankets and cooking supplies out of the car and walked towards the giant plume of smoke we saw ahead in the distance. Once we reached the celebration we set ourselves around one of the bonfires. The group's cook made us hot dogs with ketchup on them, along with hot drinks throughout the evening. There was even a bit of whiskey being passed around. One of the guides pulled me up from the fire and brought me to the dancing circle which had formed around the band playing charangos. He taught me the local dances and we had a lot of fun while waiting for the sun to come up.

The hours passed and the drinking and dancing went on. Soon it was time for the sun and we gathered up all our stuff and climbed the nearby mountain in near darkness until we reached the ruins. We couldn't see neither the ruins nor the mountains and views around us yet, but there was a beautiful eerie magic about the place. There were candles burning in the little archways of the ruins, letting us have a glimpse of their outline before the sun came. I took some photos of this stunning sight.

Once the sun started rising and we could see a bit more, the speeches began. Various Bolivian diplomats said a few words (that no one seemed to pay attention to) and then came the coca leaves and the alcohol, which were handed out to the diplomats to chew and drink.

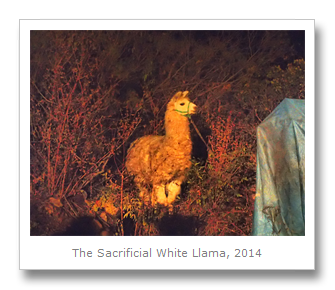

There was suddenly an announcement made - one which everyone had been waiting for. It was time for the young, white llama to become a sacrificial offering to Pachamama. We went out to a sacrificial stone (a new one, the old Incan stone was nearby but is no longer used to preserve it) – a stone that was perfectly positioned for the sun to shine its rays directly on the offering. There was a bonfire near the stone on which served as a ‘table of offerings,’ to both Mother Earth, Pachamama, and the Sun God, Inti. The young llama was brought to the offering table to have its throat cut, in order for its blood to run down the stone and into the bonfire/offering table. These collective offerings were supposed to ensure future land productivity and earthly prosperity.

Many people couldn't watch this part of the celebration, and for good reason. The following photos and videos are quite graphic, hence the warnings I put on the title of this blog post. Everyone gathered in a circle around the llama while a few men held the beast down on the rock. The leaders of the ceremony, including the shaman, took a knife and started to cut through the llama's throat, letting the blood flow down the ceremonial rock. I happened to stand in the 'perfectly' worst position possible - right in the line of fire, unfortunately. Somehow it didn't register with me (probably my lack of experience at attending sacrifices) that standing near the neck would cause me to become covered in blood from the llama's cut arteries. I took a video of the llama being cut open.

I watched as the shaman then went from cutting the llama's throat to making a cut in its' side and 'digging around' (yikes) attempting to get the llama's heart out of its' body - reading the organ gives the forecast for the following year's harvest. While trying to get the llama's heart out the llama fell off the sacrificial rock and onto the floor in front of me. A few moments later the shaman managed to get the heart, spoke some words in Aymara, and then raised the heart to the sky before throwing its' heart on the bonfire/offering table to burn for the Gods.

Just at this moment (the timing was spookily perfect) the strong rays of the sun came streaming down from the sky directly onto the fire and the stone in front of us - nearly blinding us! Everyone simultaneously raised their hands towards the sky while facing the sun's rays. A few moments later the shaman turned to me (I was clearly the only foreigner at the event, and stood out quite a lot) and dipped the tip of one of his finger in the still-dripping blood of the llama from the side of the sacrificial rock and then marked my forehead with a blessing and a smile. Not your typical touristic experience, but a memorable one. Once the ceremony was concluded the llama was brought away to be cut up and cooked, and our group walked back to the ruins.

A crucial note about the llama sacrifice: While the sacrifice of a young, live white llama is essential to the indigenous Aymara (and Incan) celebrations honoring Pachamama, the practice screams (literally, in the llama’s case) of animal cruelty. After the ceremony I decided to look up some information about animal welfare. Wikipedia’s listing about ‘cruelty to animals’ noted the ‘animal welfare position’ which supposedly states that: “…there is nothing inherently wrong with using animals for human purposes, such as food, clothing, entertainment, and research, but that it should be done in a humane way that minimizes unnecessary pain and suffering.” There is another school of thought which asks for animal rights, in other words, for animals to never be considered property or used for commercial purposes.

Another website I came across was the American Veterinary Medical Association’s article ‘What is animal welfare?’ Their article gives a bullet point list which includes that animals:

- … [are used responsibly] for human purposes, such as companionship, food, fiber, recreation, work, education, exhibition, and research conducted for the benefit of both humans and animals.

- … shall be treated with respect and dignity throughout their lives and, when necessary, provided a humane death.

Clearly the ceremony I attended did not give the llama a humane death, nor was the ‘human purpose’ it was used for beneficial to both the humans and the animals. So should the practice continue? In more touristic areas which conduct a June solstice ceremony such as at the Tiwanaku (Aymara) ruins in La Paz or the Sacsayhuaman (Incan) ruins in Peru a live llama sacrifice is no longer preformed and either a (dead) llama fetus offering is burned (as in Tiwanaku) or the llama sacrifice is only ‘acted out’ instead (as in Sacsayhuaman.) Since I was the only tourist at the Inkallajta (Incan) ruins, the area is clearly not a main touristic site yet and does not attract enough attention from foreigners that a live llama sacrifice might be detrimental to attendance or Bolivia’s reputation. I saw a few locals cringe and turn away during the llama sacrifice, but no sign of any Bolivians protesting the act.

One must also consider the rights of indigenous communities to continue their traditions and practices. Does this method of sacrificing a llama become more ‘OK’ because it has been practiced by the pre-Incan and Incan people for thousands of years? Do they have a right to continue the sacrifice because of this? Or is this just a practice which is outdated and (with new thoughts on animal welfare/rights) should be considered selfish and inhumane on the part of the participants? Certainly other indigenous practices (such as human sacrifice and body mutilation) performed by both indigenous Bolivians and tribes in other countries are considered too inhumane to be allowed to continue, despite their status as part of the ‘local indigenous traditions and practices.’

If this is considered to be the case at Inkallajta, is there another way tradition can be honored while increasing standards of decency and respect towards animals? Clearly at Tiwanaku and Sacsayhuaman this thought has already been considered and an alternative reached. But what will happen at Inkallajta as the area around Cochabamba becomes ever more touristic? We’ll have to see…

It was time for us to take a walk around the Incan ruins.

Inkallajta is a well-preserved Incan stone fortress and administrative area of 67 hectares built in the mid 1400’s, likely during the rule of Tupa Inca Yupanqui. Compared to Tiwanaku or Machu Picchu, where many people go to celebrate the Aymara New Year, this sight is actually much better preserved though smaller.

Yet smaller is relative, because the site has forty buildings including: a ‘Kallanka’ or main hall with numerous, typically Incan niches. Also a Pre-Incan astronomical observatory, religious rooms, military barracks, university rooms (for the housing of students and teachers) and a waterfall with a microclimate around it known as Pajcha, or the ‘Waterfall of the Virgins’ because the Incan virgins supposedly bathed there. There was also a large, strategically placed house of unknown purpose nearby. I reckon it was likely the mansion of an Incan noblemen, as it had a perfect view of the virgin bathing site. My favorite aspect of the ruins was a series of defensive walls above a high valley which had strategically shaped windows from which it was easy to fire out without being fired back at. Overall I was really impressed by these ruins – they and their history should definitely get more attention from tourists!

The history of the Incans in the region went like this:

“Once they had conquered the Collao territories, the Incas marched deep into the semi-tropical valleys of what now are the Cochabamba and Santa Cruz states. There, they established a series of cities, specially fortified to control the advances of the Chiriguano indians. The Incas created… in the state of Cochabamba… the fortified city of Incallajta.” (World Heritage Organization)

My camera died but through the help of some of my new friends I met at the event I was able to get some photos of myself at the ruins anyways!

Our exploration of the ruins finished, we gathered in the center of the Kallanka and had a delicious cooked lunch the guide had prepared while we were on our tour of the ruins. Once the dog roaming around us had managed to snag the leftover meat we were all ready to head back. We gathered our stuff together and walked towards the festival location from the night before where the car and driver were waiting. When we found our driver he looked pretty tired. Really tired. It unfortunately took getting into the car with him for the short ride to where the rest of our group was waiting for us to figure out that he was completely drunk! As we drove towards our group some members near the road started waving their hands and yelling at the driver to stop. He was too wasted to stop quickly enough and ran over the cooking pot and its stand.

Clearly this was not good and our group decided we were not going to go any further in the car with this guy. The driver got angry we weren’t coming in the car and sped off- good riddance- and we waited for our guide to find another ride for us. Most of the other tour groups and buses had already left the celebration earlier that morning so we were a bit stuck. It took our guide 4 hours (we were just talking on the side of the road during this time, and watching the drunk Bolivians fall on their asses around us) to find another minibus for us to take to get back to Cochabamba.

The new minibus driver (who I believe was also drunk, but less drunk than our first driver) sped like an absolutely madman to get back to the city, sometimes nearly 50 or 60 kilometers over the posted speed limit (if there was any, which there often wasn’t.) I had to ask the driver to slow down (he didn’t listen to my request until I asked a *male* to ask him for me, and then he only slowed down a little) because myself and two Bolivian girls in the backseat were nearly having heart attacks at how fast he was driving. When we got back to Cocha it took me awhile to find the hotel, but eventually found Colin there asking the front desk to phone the tour agency to try to find me. We ended up being quite a few hours late, so I’m not surprised that he started to worry. But now I was back with llama blood all over our backpack and quite a story to tell!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment