We crossed the Argentine-Chilean border for the fifth time on the 29th December after spending Christmas in Puerto Natales in Chile. This was to be our last planned stint in Argentina, to visit some of the more well-trodden parts of Argentine Patagonia; the tourist towns of El Calafate and El Chalten. Unfortunately it was right in the middle of high season in the most expensive part of South America, but we had chosen to wait for the summer before visiting Patagonia so that there would be more options of things to do, and so that the passes and roads would be open and not closed with snow.

Crossing the border itself is a mere formality, especially with a bus and even though the procedures are a drag after the fifth time, they are pretty quick and painless, so long as you do not bring fruit across the border which is prohibited for reasons passing understanding (ridiculous as the same fruit is sold both sides of the border in the supermarkets).

The bus arrived in El Calafate and we tried to get some information about a tour of La Leona Petrified Forest from the tourist information office and the same tour company we had used in Puerto Madryn whilst whale watching, El Chalten Travel. However the tourist information people were pretty useless, and had no real advice, and the woman working at El Chalten was an extremely rude and unhelpful person more concerned with her Facebook page than talking to customers. We jumped in a taxi to our hotel, Hosteria Lupama, which we had booked in advance online.

Located out of town and at the top of a hill in a maze of unmarked roads, it was not easy to find, but once we got there we were pretty happy with the room and facilities, which included a small pool. The double room had cost us $US25 via booking.com which was a steal – we think they had been mismanaging the online booking system, as the room jumped to over $US1200+ the next night which must have been a mistake. We waited until later the next day and asked them if we could keep the room, but they asked for $US90 and would not give a discount even though it was clear they would never fill the room – oh well.

We relaxed in the pool, caught up on some sleep and arranged to stay in a nearby apartment building for New Years. Our first foray into El Calafate was not very impressive – clearly the townsfolk are all pretty jaded, having to deal with rich demanding tourists and huge groups of aggressive Israelis on a regular basis. El Calafate is the closest town to a famously accessible glacier, named Perito Moreno after the Argentine explorer, and it is this that has caused the city to expand so rapidly in the 1990s and then again by 20% since 2005. Everything about the town screams tourism, including the tacky souvenir shops, the inflated prices, and the veneer of fake Patagonian culture everywhere. Prices are ridiculous even for Patagonian standards, due mostly to the unfortunate situation that has allowed the trekking companies and bus companies to monopolize certain tours or transport links pushing the cost of visiting this area to horrendous new highs. All rates here are not just adjusted for inflation, they seem to be all priced at the alternative blue dollar rate, wiping out any hope of gap year students and backpackers to really get a good feel for the area. This is not helped by the influx of already jaded Argentines from Buenos Aires who came here to escape the pressures of city life only to replace that with the pressures of a demanding tourist industry. Everyone we met on the first day was either passively and ignorantly nonchalant to the point of being rude, or just downright aggressively rude. Needless to say we did not feel the warm welcome embrace of El Calafate – there are so many tourists that dump their money here whilst transiting through on tours that plain old backpackers like us are just an inconvenience.

Screw them. We decided to have a nice time on New Years, so we stayed in, drank wine, and watched movies. Our kitchenette was pretty useless (a gas stove with only one small saucepan with tiny handles!), but we made the most of it all, and at least we saved money on going out to an expensive restaurant (they are all expensive in Cafayate, and the service is so bad we just walked out of at least three places that first day).

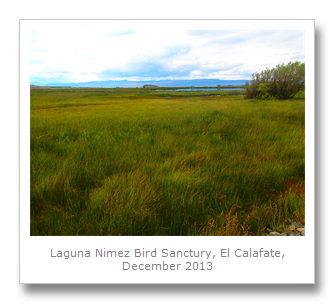

Whilst our experience with the locals was not quite as positive as we would have liked (and there are many other Tripadvisor reviews which bemoan the so-called ‘services’ in the town), I am sure many people have a good time here. I took a walk on New Years Eve, and found the adjacent Bird Reserve had a notice on it that said it was free all day. It seemed to me to be a magnanimous gesture but then Francesca reminded me that the owners probably just did not want to pay someone holiday wages to be there on New Years, and so just left it open. Who knows, huh?

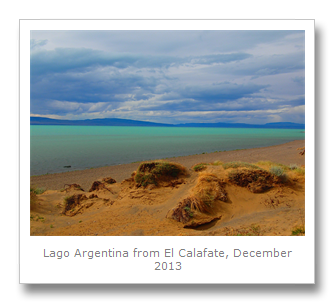

Laguna Nimez Bird Sanctuary is found in the North part of the town on the Southern shore of Lago Argentino. The biggest freshwater lake in Argentina, it can reach up to 500 meters deep, and is 1466 kilometers squared. A glacial lake like many others in Argentine Patagonia and the Lake District, it is the lake on which the famous Perito Moreno Glacier itself is found. Now stocked with tons of trout, which are apparently a menace to the local ecosystem since introduction, it is very popular with fishermen and the birds that hang out in the reserve. Walking around the bird sanctuary was very relaxing and I saw lots of ducks, geese, birds of prey, ibis and even one errant flamingo that was asleep on one leg. The trails are easy, flat, if not a little wet, and there were even bird watching huts you could sit in and watch the young birds who were in nests in the reeds.

The only other place of note that we went to in El Calafate was the Centro de Interpretacion Historica. Stretching back to the Jurassic era of the dinosaurs, the museum told the story of Patagonia through fossils, rock art, what we know about the indigenous people and the European history since colonization took place.

My favorite dinosaur they had reconstructed was the Austroraptor Cabazaii, which has a huge jawbone. These beasts grew up to 5 meters in length, and lived around 70 million years ago in the Cretaceous period.

We also learnt a lot about the routes of early humans into South America. More than we found out elsewhere, because, although we knew there were three waves of human visitors from 15,000 years ago, the genetic mapping done in Patagonia tells a little more about how and when these people came to migrate here. Once the ice caps (which were much larger than they are now, with the Southern and Northern Patagonian Ice Field both being connected) began to recede, the humans made their way down the coast from across the land bridge between present-day USA and Russia.

The land was a lot bigger back then – with more water tied up in the glaciers, there was more land. Once the ice melted, South America became a lot smaller – natural flooding due to climate change.

Once humans reached South America, they migrated and populated quickly. This museum went all out and described this as the number one reason that so many of the mega-fauna (big mammals such as the glyptodon) became extinct. Other museums have been more cautious – attributing the change to various other factors.

Whatever happened to the mega-fauna, also happened to the indians when Europeans arrived. We read about one group of Aonikenk people who fought back against the Spanish. Led by Chief Inakayal, they were quickly killed or captured. His people were forced to work in the Museum of Natural Science in La Plata (when the famous ‘philanthropist’ Perito Moreno was director – showing that history revisionists have carefully white-washed his reputation to show he was a good guy, not a slave owner). When the Aonikenk died, they would be preserved and displayed in glass cases in the anthropology rooms. When the chief saw his wife in a glass case, he killed himself by jumping from some stairs. Disturbing. The museum is the first we have seen in Argentina to acknowledge the dreadful war waged against the native people, highlighting it as genocide.

We were in El Cafayate until the 5th January because we were waiting our turn with the company who have monopolized treks on the glacier, Helio y Aventura. The name means Ice and Adventure, and although they did not disappoint and gave us a great tour it is still a shame that prices are so inflated due to the monopoly that they have somehow arranged to have exclusive access to the glacier. Their ‘Big Ice’ trek which allows for around 5 hours on the ice was $US200 each, so pretty expensive for the budget traveller! Don’t worry though, there are also numerous other options to see glaciers in the North, especially in Chile. You can trek glaciers cheaper, not to mention see glaciers for next to nothing, hanging from mountains in various National Parks or from buses on several routes. The Perito Moreno Glacier is not the only option!

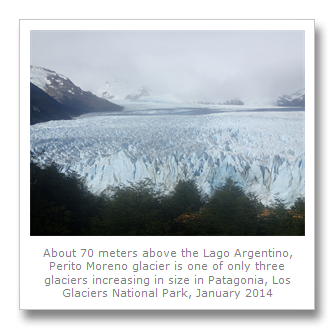

It is however THE easiest glacier to access. A part of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, Perito Moreno Glacier is only about 40 kilometers from where we visited Torres del Paine National Park (where we saw Glacier Grey). This ice field is vast. Covering over 12,000 kilometers squared, it contains 48 separate glaciers and is the biggest ice cap in the world outside of Antarctica and Greenland. The Southern and Northern Ice Fields were connected in the last glacial period and covered Southern Chile back when the land mass of South America was bigger and you could have walked to the Falkland’s. With the end of the ice age, the seas rose and the land is now much smaller.

Our bus drove us from El Calafate along ruta 11 along the Northern part of an area of Lago Argentino which is almost cut off from the rest by the glacier. Along winding forested hills (there is verdant rainforest all along the Eastern sides of the Andes from Columbia all the way down to Southern Patagonia because of the rain that comes from the Pacific), our guide laid out the plan for us, and advised us in Spanish and perfect English what the day was going to involve, and all about the geology and history of the glacier and ice fields.

We arrived at the entrance to Los Glaciers National Park where the glacier (and several others) was located. We stopped and the park rangers boarded the bus to take the $80 pesos ($US12) for the entrance tickets (tours in South America often do not include entrance fees or guides).

We drove to the specially constructed wooden walkways erected at the tip of the glacier across the lake from it and spent an hour and a half viewing the glacier and watched some ice calve off of it. Calving is the process in which ice breaks from a glacier and becomes an iceberg, usually due to climate (especially during summer) and plain old gravity. This is how the iceberg which sunk the Titanic was formed after it calved away from Greenland’s ice cap.

This was the first time I had ever seen a non-hanging (mountain-based) glacier for the first time, up close. Glacier Grey was really impressive in Torres del Paine National Park, but we saw that from afar due to a knee injury I had picked up from hiking; so it was awesome to see Perito Moreno Glacier so close.

It is best to get to the glacier early, as we got the viewing platforms to ourselves before the hordes descended. Francesca and I shot off the bus as quick as we could to get the longest time to look at the glacier. The walkways seemed really well constructed and were really well placed. The top level gave excellent overviews of the glacier, a panorama of the North and South faces. Cloud obscured our view further away as the glacier disappeared up a short incline up to where it connected to Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

The further down the walkway, the closer you got to the ice – every few minutes we would hear a sound like thunder rolling when ice would calve from the glacier. We even saw ice falling ourselves and crashing into the lake below, causing huge waves.

Perito Moreno is one of only three Patagonian glaciers which are growing, and it is still hotly (no pun intended) debated within scientific circles as to why. Some say it is Al Gore’s inconvenient truth, and an argument against Global Warming. However, the sad reality is that most of the glaciers in the world are melting away, and shrinking rapidly year on year. This is causing sea levels to rise, and within 50 years the oceans and seas will be at least 3 feet higher than they are in 2013.

This glacier is actually growing due to the local topography and positioning of the ice. The Pacific Ocean winds come in from the West dumping seawater as rain onto the fjords and islands of Western Chile. The mountains at the Patagonian Ice Fields are so high, the rain there turns to snow because of the cold, and tons of snow is dumped every year onto it. This is not enough to save most dying, or receding glaciers, but Perito Moreno has an advantage.

A slight decline that the glacier is advancing down ends at Lago Argentino into which the glacier calves and dumps its ice. Normally, as elsewhere, this would be the end of the story with climate change causing the rapid deflation of the ice. However, the glacier is pushing down at just the right point to hit the back of the lake, at a point where it is not very wide. This pressure has caused the glacier to slow down, and therefore not dump too much ice as to recede.

A famous phenomena called The Rupture occurs when the glacier touches the other side of the lake. It forms a blockage or dam across the lake and the water starts wearing away the ice at the bottom (the water is warmer than the ice). The water breaks through the bottom of the ice forming an ice bridge at the top. This eventually collapses, or calves, under its own weight into the water. I really wanted to see this but it had already happened 4 days before (according to the guide), and only happens between once per year to once every decade – so hard to see.

We did see a lot of ice in the water consistent with the guides story, and while we were there we saw other small sections falling, which was still pretty awesome. However, research has since shown that the guide lied about The Rupture occurring 4 days before we visited on the 4th January. Why he did this, we don’t know – maybe to manage everyone’s expectations because the glacier was not an ice bridge at the time? I don’t know, but the credibility has gone down massively – a common complaint with guides in South America.

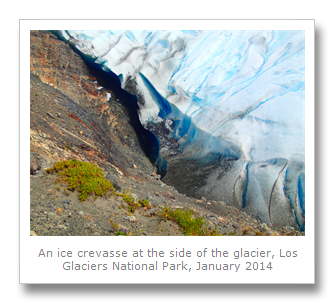

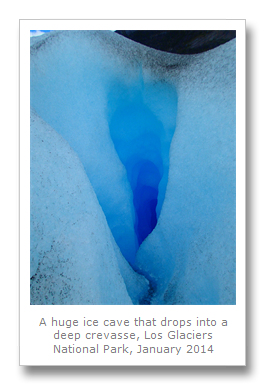

Anyway. The most impressive part of the ice though is the color. The ice was a deep blue, extremely pretty – caused by the absorption of light at the red end of the spectrum. The more the light has to travel (that is, the thicker the ice), the deeper blue we saw. The glacier was filled with ruptures, crevasses, caves and amazing formations that contained this really cool (pun intended) color.

After we got some good photos we jumped back on the bus and then we took a company boat from across the lake and navigated over to a refuge, or cabin, next to the glacier itself. This refugio, or refuge, was at the base of a 1 hour hike to where the ‘Big Ice’ 5 hour glacier trek started. We had brought our own lunch and the plan was to eat it on the glacier.

The boat ride was short but sweet. We actually saw a huge piece of ice calve from the glacier on the way over, but it was far enough away to cause no concern.

We were helped from the boat, given a briefing by park rangers; our new guides, and we set off for the base camp at the start of the glacier, which was at the end of a tiring hour long forest and rocky trek. We had bought with us warm clothes for the unpredictable weather that can come off of the ice cap, sun screen because the ozone is completely depleted in Patagonia, our lunch and some water. The water in the streams and on the glacier is fine to drink so don’t waste money on bottled stuff. Do drink plenty though, as the guides walk fast – there have been a lot of Tripadvisor reviews about pushy guides berating people for not keeping up with the hike – even after you pay $US200 each! We did not experience any of that though, the guides were chatty and safety conscious.

We were fitted for crampons at the end of the walk, and carried them down to the ice where the guides put them on over our boots. They all seemed worn but perfectly usable. We did not need other safety equipment, as the guides carried extra crampons, ice picks and there was rescue equipment placed in caches at strategic places on the glacier itself. We also wore harnesses in case anyone fell down a crevasse and needed pulling out.

The wind was pretty strong at first and my hat blew away and was irretrievable at the bottom of some glacial cave, so definitely not a good start for me or for the poor glacier. I guess that is the price of tourism – hopefully anyone reading this will make sure they do not follow my suit and litter, even accidentally, on this natural wonder.

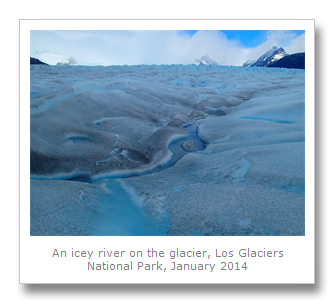

We waked single file, following the guide, with a support guide walking to our side. We past easy to cross streams, pouring from the glacier. Small cracks and holes caused by carbon and dust which absorb the sun’s heat thereby forming puddles that grow and grow until they become huge bore holes down to the surface of the glacier, some 70 meters below. This water run-off was the cause of the rivers and lakes we had seen all over this area of Patagonia, and it is this that will cause the seas to rise and displace hundreds of millions of people within our lifetimes.

We past a huge ice cave, which we returned to before leaving the glacier to take pictures. It’s not certain how far down the cave went, but the water sounded like a torrent running off the cave’s walls to the black hole at its bottom. We all wore harnesses around our waists, because if you fall into a crevasse the only way out is back up, so you would have to tie something that was lowered to you and be pulled back up. Careful!

Nice sized lagunas, deeper and deeper crevasses, glacial ridges and numerous little ice rivers were crossed, and it was fairly easy going. The crampons did their job excellently, and the guides helped us over the sheer drops, and cut stairs into some of the ice so we could get about more easily. It was a lot of fun.

The cloud in the distance had cleared enough for us to see all the way back up the glacier to the ice cap. Just ice running for hundreds of kilometers. It is no wonder the indigenous people never explored this region – it must have seemed like it went on forever to them. We could see over the other side of the glacier – it is about 3 kilometers wide at its widest point. The glacier kind of came down in the middle and dipped and then rose again, with the valley floor, which helped slow the glacier down. This and the pushing against the lakes other side allows the glacier to keep existing and not expand to far and then deflate in on itself.

The surrounding mountains had huge grooves going at least another 100 meters up, which is where the glacier used to be at the height of the ice age 22,000 years ago. Proof that cyclically, we are coming to the end of this ice age.

The guides found us a shielded spot against some upturned ice where we were to sit and contemplate the cold vastness whilst having lunch. We had packed some sandwiches, nothing fancy, and then we all set off again.

After a while I was glad to be heading back, as using crampons is still quite tough on the ankles and knees – I must be getting old. It was an amazing experience, and much easier than other glaciers I had heard of, which require more ice climbing and specialized equipment. Again, we were extremely lucky with the weather, with no rain, little wind, and no snow at all – other trips to the ice cap have not been so fortunate.

We came back the way we had come, back along the rocky trail, past a beautiful waterfall, and through the Southern beech forest to the cabin where we grabbed the things we had left there and made our way back to the boat. A beautiful day, I still got sunburnt even using factor 60 – because I had lost my hat. Once back on the boat we all were given a whisky with glacier ice in it! It was not explicably stated this was glacier ice actually, but it probably was – not exactly sustainable tourism, perhaps? I do not know…

We got back to El Calafate and left the next day, the 5th January. We were extremely happy to be leaving the city behind and we headed on to the next town, around huge lake to the North, to El Chalten. The best thing that can be said about El Calafate is that it is named after the Patagonian Barberry, calafate, which we have seen everywhere in Patagonia. This is made into jams, jellies and ice-creams, which we tried in an ice cream parlor – delicious! It tasted to me of gooseberry – definitely a hit, but don’t bother going to El Calafate to get it – it’s everywhere down here…

If El Calafate had knocked our love for Argentina, El Chalten hit it over the head with a bat, kicked it to the floor and spat on it. Simply one of the worst manufactured towns we have ever been to! All the hostels were either full or extremely expensive, the bus station information was useless and rude, the town’s solo ATM machine ran out of money, and there were even these ridiculous wanted posters of a persona non grata, not me I hasten to add, posted around town.

***RANT***

Two young mountaineers, one American (Hayden Kennedy) and one Canadian (Jason Kruk), climbed the face of Mount Torre, a mountain in the South Patagonian Ice Field. They climbed a route that has come to be known as The Compressor, named after the tool that was used to place 400 climbing bolts and ladders by the Italian Alpinist climber Cesare Maestri in 1970. Maestri himself had been angered by the disbelief of the climbing community that he had, indeed, scaled the face of the mountain in 1959 and so returned and controversially placed the bolts to get him up there safely (his guide died on the first climb). After much debate in the climbing community, a vote was cast in 2007 that the bolts would be left in place for historic posterity. However, Kennedy and Kruk, after summiting with the use of only 5 bolts, unilaterally decided to remove Maestri’s 400 bolts themselves and so cut them off on their way back down. Arrested and lambasted by the locals and the current crop of Italian climbers, yet praised by their American contemporaries, they had the bolts confiscated and left El Chalten late 2012.

They returned to the town a few weeks before we got there in late 2013, the community hounding them with posters, fliers and leaflets in a hate campaign designed to elicit a public apology, or make them leave the town for good. It was in this atmosphere that we entered El Chalten, finding it to be an arrogant and rude building site – a manufactured town which was conceived and founded in 1985 to settle a border dispute between Chile and Argentina (one which still goes on) and to exploit tourism.

The Italian camp, who are now harassing the two young mountaineers, are angry because their ego has been hurt when their history was, at least in their eyes, desecrated. The Americans say they want only to ‘respect the mountain’ – by which they really mean they want to ignore everyone’s express wishes and dictatorially decide what is right, even when it flies in the face of other people’s feelings. Francesca and I say that both groups are guilty of aggressive egotism, to the point where all common sense and decency has been left behind, creating an atmosphere of animosity and belligerence which seems to seep through in all of the attitudes and interactions in the region. Arrogance, egotism and rudeness. The mountaineering community has long since been accused of all three things – not surprising really from a group so selfish that they leave their fellow human beings to die just so that they can continue their costly ascents.

From the bitter border dispute, to the bitter and fruitless dispute about some nails in a rock, the regions petty squabbles remind me of a quote by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, who compared the Falklands Conflict to “two bald men, fighting over a comb.”

The same can be said for the egotistical view of young backpackers who insist they are ‘travellers’ and not ‘tourists’ – fake and ridiculous purism that we cannot be bothered to entertain. Get over yourself, love, you’re on holiday.

***RANT OVER***

The town has four HI hostels, and the one we stayed in, Condor de los Andes, seemed promising at first. However, once we got into our room, things changed. The lady was just as penny-pinching and greedy as everyone in the region, arguing about about how much laundry we had in the basket. We took the clothes back and found a cheaper less Scrooge-like launderette to use in town (‘town’ is one long street, named, of course, San Martin).

A town where the bus stops at the park rangers station before taking you to the bus station, El Chalten is all about one thing. Trekking. The self-titled Capital Nacional del Trekking, the rangers helpfully tell you all about what is on offer in the town. As we were pretty much fed up with trekking, we decided to do the two easiest treks and then leave the area.

We left our bags in the hostel and went to our first walk, mirador los condors, or viewpoint of the condors. We saw two nesting pairs circling high up, near the top of the viewpoint as we ascended. It was an easy climb up and down, but as it started to rain when we neared the top, the condors went away for the exact length of time we were up there. We could see the town – still looking like a building site, and the beautiful rivers and mountains all around.

Flanked to the West by Cerro Torre (the one which has created all the hoopla), and Cerro Fitzroy, El Chalten has an unpredictable climate due to its proximity with the ice cap. In a move typical in South America, Cerro Fitzroy was actually renamed from Chalten by the Tehuelche natives. A sacred mountain, where man was born, Chalten means ‘smoking mountain’, and lived up to its name when we were there as it was obscured by cloud most of the time. Now called Fitzroy after the captain of Darwin’s Beagle, it is ranked as one of the hardest mountains to climb, even though it is only 2,685 meters high.

Without the condors or the view of the famous mountains we went back down, and got some food on San Martin. One thing El Chalten has is some great Western-style food places. After spending a year in South America we were grateful to see waffles on the menu!

After lunch we headed to the other easy walk, a few kilometers up the road (drivable) to a short trail through trees to a 20 meter waterfall.

We met a nice couple from Australia who were seasoned travellers who gave us some great tips, specifically about travel in Russia.

After leaving this trail, we made our way back to the hostel, where we managed to pay with cash after changing some Chilean pesos, and we got on the nightmare bus from hell to the next destination in the North.

I’ll leave that story for Francesca to tell you for next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment