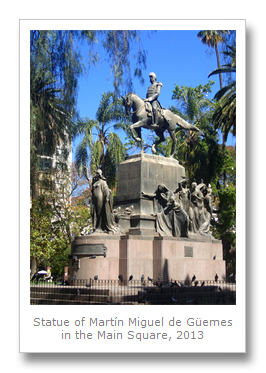

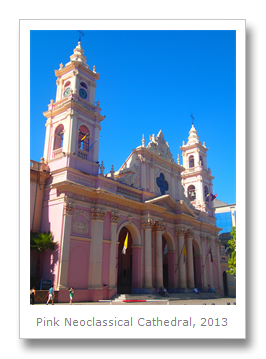

Finally we decided to return to Salta, one of the most populous, popular, and - according to nearly everyone we spoke with – beautiful, areas in Argentina. We took the bus back to Salta from Jujuy on October 20th, enjoying the ride back much better than the way there as Colin wasn’t sick anymore. Once we got to the bus station we were stunned to find our medicine bag was actually there! After collecting it, we grabbed a taxi to our hotel – La Pousada de Don Simon. Cheap, yet with really small rooms and shared bathrooms, the owner made up for the thin walls by having connections to cheap tours that we were interested in. But first we wanted to see Salta, so we headed to the 9th of July square in the center of town. Surrounded by colonial architecture from the late 1500’s, this city was led by General Martin Miguel de Güemes who used the city as a strategic spot during the War of Independence, as it is in between Lima, Peru and the capital of Buenos Aires. We would later see the burial spot of General Güemes, at one of the elaborate cathedrals off the main square. Instead of heading for Güemes straight after a burger lunch, we went for another corpse- this one removed from its final resting place…

Mummies. The first museum we ventured into was known as one of the best in Northern Argentina: MAAM, or the Museum of High Mountain Archaeology. Walking into the first room we were shown a video of a group of archaeologists climbing up Llullaillaco Volcano, 6,739 meters high in search of one of the 200+ “high altitude sanctuaries” in the Andes. This volcano was an area sacred to the Incan culture, used in their ritual ceremonies. In fact, mountains or “apus” were considered to be gods and protectors of nearby communities.

High Mountain Archeology combines the sport of mountaineering with archaeology, and from the 1950’s to the 1990’s the Llullaillaco Volcano was surveyed and explored for archeological remains. In the first display rooms we entered post-video, we saw objects and clothing from these first exploratory climbs including the important mountaineering diary of Austrian Matthias Rebirtch from the 1960’s.

When the archaeologists arrived at the top of Llullaillace, they discovered “double circular huts” which contained the mummies of three Inca children each buried with specific ritual objects. While all three children are still preserved in amazing condition, there is only one child on display at the museum at any given time in order to keep them in this condition, while the others are protected using cryopreservation which utilizes low temperatures in specially-built capsules and low oxygen.

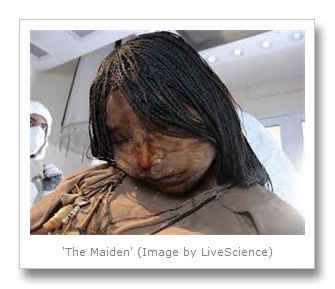

The two children which weren’t on display at the time, were known as ‘the boy’ and ‘the maiden.’ We did get to read about in the final room we entered. The boy was a seven year old with white feathers in his short hair. He was buried with a miniature llama caravan and finely dressed men. We also saw images of a 15-year-old girl known as ‘the maiden.’ She had many ornaments with her of gold and silver, and while we didn’t see this, she supposedly has coca leaves still in her mouth.

The child we saw on display was the Lightning Girl, a six year old girl who got her name because she had been struck by a bolt of lightning during some time in the last centuries after she was buried. It was really strange to see a little girl who looked so real sitting dressed in what you could tell was a colorful outfit. There was still color in her face in the rare place not darkened by lightning, and her hair looked like it could be still growing.

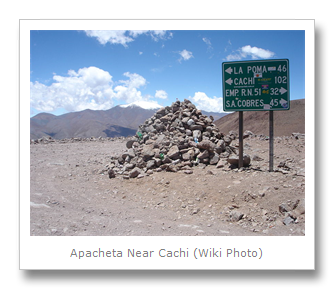

From the discovery of these children, researchers are able to put together a more complete timeline for the human occupation of Northwest Argentina. The first group of hunter-gatherers lived in the area 10,000 years ago and they utilized stone tools. Then, 3,000 years ago these nomadic people began to settle into farming communities. In approximately 1000 BCE large communities began to form which culminated in the Incas’ influence reaching the area in the 1400’s with the growth of their extensive road and communication (mail) systems. We saw evidence of this road system by learning about special rock piles/shrines called “apachetas” which were important in Andean society. Apachetas indicated the highest point in a road and by leaving a rock, one marks their presence in the area. These apachetas grew as the Incan road system grew, which was due to additional lands falling under Incan control. Things become documented more often in writing rather than visual indicators like stones after the Spanish arrived just 100 years later in the 1500’s, but much knowledge can still be gained about the Incas from the ancient artifacts left behind.

Some of this knowledge is that the lands under Incan control were known as Tawantisuyu – with Cusco in the center - and was divided into four regions known as “suyus:” Northwestern Chinchaysuyu, Northeastern Antisuyu, Southeastern Collasuyu, and South-Southwestern Cuntisuyu. These suyus had to pay tributary to the main Incan ruler in Cusco and send their most beautiful and healthy children (considered the purest and ‘best’ humans) between age 6 and 15 to participate in “ritual marriages,” supposedly to appease the Incan deities. Colin noted these ‘marriages’ were likely just a strategic move by the central power to keep the various regions under their control. The child mummies found on the mountain were part of this symbolic marriage, sacrificed in a ritual known as capacocha.

Capacocha started with the children being treated brilliantly, akin to Incan royalty with delicious foods and rich clothing and jewels – with the Incan emperor even a feast in Cuzco in their honor. Unfortunately after the feast is where the kids’ luck would run out. Next, the Incan high priests would take the children (with the aid of coca leaves and alcohol) to the mountaintops and sacrifice them – either by killing them outright or leaving them to die of exposure. Their bodies mummified in this dry and cold climate and remained until archeologists uncovered them and brought them to the museum.

One of the last rooms we entered contained a map of the mountaintops on which evidence of a capacocha ritual being preformed. Out of the 27 bodies uncovered at capacocha spots, 8 of them were sacrificed children. In the room was one of these children, an 8-year-old female Incan mummy known as the Queen of the Hill. Discovered in the 1920’s in a place called Chuscha Hill (but a 5,000 meter high hill!) in Salta, she suffers from the worst state of deterioration of all of the mummies due to mismanagement of her preservation, because she spent a long time in private collections before ending up at the museum. Still, we could see some of her remains including her dark braided hair on her head. She was found with a multicolored bag containing corn and peanuts and a necklace of seashells from the Chilean/Peruvian shore.

The final room of the museum had photos and videos of the areas' bid to have the 6,000 km Quapaq Nan or extended Incan trail (the part including Northern Argentina) included as a UNESCO world heritage site.

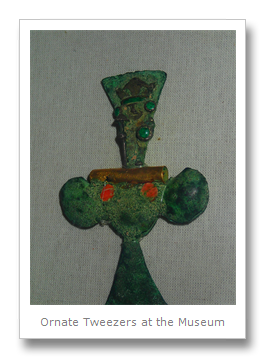

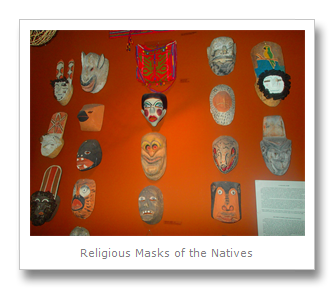

Next Colin and I headed to Salta’s town hall, which was also the most complete cabildo remaining in Argentina. The adobe structure is now a historical museum divided into three sections. The first area showed us some indigenous pottery and tools, the second showed us colonial artifacts, and the third showed us the independence revolution. Everything was in Spanish, but we did gain a few photos!

After the cabildo we popped into the Centro Cultural Americana for a quick rest. This building started out as a Jesuit Church in the 16th century, which remained until the 18th century. In 1909 the building became a social club called the “Club 20 of February,” in the 1950’s it became a government house, and by 1987 it gained its current use as a historical building/museum.

There wasn’t much to see there but we wandered around for a while before checking out an ornate (yet covered in scaffolding at the time we saw it) church – the Iglesia San Francisco. Here we found the grave of General Martin Miguel de Güemes, the Argentine Independence War hero I mentioned earlier. Highly educated, Güemes was also a talented military leader who trained gauchos to use guerrilla warfare to fight for Argentina’s independence, but was eventually shot in the back during a military operation and died as his gauchos took over Salta.

Since it was pretty hot out, Colin and I decided to head back to our hostel and get some rest from the long day. The next morning, October 21st, we decided to walk to an archeology museum we had read some good things about on TripAdvisor called Museo Pajcha Arte Etnico. When we got there another couple was already being led around by Diego, the museum curator. We weren’t asked if we wanted a guide (we learned later this was an extra charge) but after leading the other couple into another room, Diego came to guide us. The museum was small, but there were some interesting things to see… however, it was quite frustrating that the guide was rushing around like a headless chicken trying to guide two groups who were at different points in the exhibits. Moreover, the lights would be turned off immediately after we had left a room, meaning we couldn’t go back and take a photo of anything without informing the guide. The most annoying part for me was being rudely rushed out the door 20 minutes before closing, even though we asked what the closing time was when we arrived!

At the museum was a collection of Pre-Columbian pottery from Peru, Bolivia, Northern Chile and Argentina which ranged in date from 100 CE to 1400 CE. There were also metal objects such as ancient tweezers and hair pins, and colorful Nazca and Maya clothing patterns – both samples from ancient times and their modern equivalents which we learned were shown to encourage the craft in local children.

One of my favorite sections of the exhibit was a few cases which gave examples of amulets used by certain South American shaman known as Kallawayas. These shaman served as intermediaries between man and divinity for their people using their knowledge of astrology and constellations. They treated by using medicines which mixed animals, vegetables, minerals, and objects of human origin to find cures for aliments. They preformed rituals addressed to mother earth, and even discovered penicillin in the ferment of bananas in the year 1000. The Kallawayas traveled long distances all around South America in search of certain curing plants including coca leaves which they ‘read’ for cures.

The amulets the Kallawayas used were divided into white and black tools. The white amulets were made from alabaster extracted from Bolivian quarries, and the black amulets were made from extracted slate and basalt. There were three different shape categories for the Kallawaya’s amulets- anthropomorphic amulets, zoomorphic, and geometric. While many people could own or make an amulet, the device was thought to need the shaman’s breath in order to be effective and render protection.

Once Colin and I went into the upstairs room we found more modern pieces such as examples of Mestizo art including a painting of the Trinity. This painted showed us three equal faces of Jesus and supposedly adapts the ‘Christian mystery to the mentality of the indigenous’ as the information including said. While no one is sure why the holy spirit is not represented in this painting by a dove, it is expected that it is an effort by the missionaries to adapt Christian imagery to ingenious beliefs in order to ease conversion and thus better control the native population.

The museum was the only thing we ended up doing that day, as we needed to sort items to send home in a box and purchase a few new shirts for Colin. The highlight of our time in Salta was our day trip on October 22nd to Cachi. We were picked up early in the morning by a tour company called La Posada and headed down the highway off into the canyons towards cactus valley!

As we began our drive, our guided discussed three important industries for Salta’s economy. Salta is responsible for 95% of the sugar production in Argentina (used for strong rum) and strongly reliant on tourism. He then pointed out the third prominent industry in Salta as we passed an example: tobacco. We saw some tobacco fields outside Salta which required extensive management -180 workers on average per kilometer squared of the plant, which grows up to 1 meter 30 cm.

The next area we passed was the lush green Jungas or jungle. This area has a subtropical ecosystem with a dry climate from October to March, and lots of great trekking. On these treks you can see tons of animals which dominate the area such as foxes, arboreal anteaters, monkeys, snakes, big cats, and 70% of Argentina’s birds! As we drove we saw something strange standing out in the trees, which the guide told us were huge spider’s nests.

As we continued driving we started going through the Puna, also known as the highlands. Here the altitude is extreme and thus special accommodations are made, especially for schoolchildren. Schools operating at over 3000 meters only run from September to May (other Argentine schools run nearly year-round) with the children staying at the school in dorms Monday to Friday because of the vast distances they have to walk to get to the school.

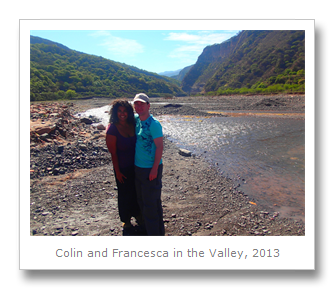

Finally we entered the Quebrada – the valleys, and the San Fernando de Escoipe Ravine. As we drove further and further in, the desert became drier and the beautiful rock formations became deeper in their colors of red and yellow. The people who live in this gorge, the Quebradonias, have a rough and somewhat isolated farming life growing onions, garlic, potatoes and cabbages. They also receive government assistance, such as solar panels provided for electricity (there are 320 days of sun per year) and iodine tablets for purification of mountain water.

Since we had been driving for a while our tour bus pulled over for a ‘technical break,’ which is what they call bathroom breaks in some parts of Argentina. I wandered around inside and found a puma skull, some peccary skins, and an armadillo shell randomly sitting on a mantelpiece! I called Colin over right away so we could get some photos.

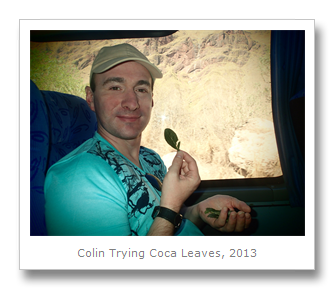

When we got back on the bus our guide announced we were climbing to an even higher altitude next. To help us deal with the altitude, he suggested we try coca leaves. He pulled out a bag and gave each of us some leaves to chew, which are legal up to 250 grams, but illegal to grow – so all leaves come from Bolivia. He taught us how to use them and we ripped off the stems and placed 8 folded up leaves in the side of our mouths. (You need at least 8 leaves.) Supposedly, the effect is similar to drinking coffee, and your mouth can go numb. My lips started tingling a little bit and the side of my cheek felt numb after awhile, but I couldn’t tell if this was due to the coca leaves or simply because I had not moved my tongue/mouth for 20 minutes. Colin hated the taste of the leaves, which I admit were pretty bitter. It took ages for any effect, and when something did happen it was so mild we weren’t impressed. The few leaves we had left went straight in the bin!

As we gained altitude (sans coca leaves), we drove on the 21 kilometer mountain route which is known locally as the Cuesta del Obispo meaning ‘bishop’s slope,’ because it was used by Monsignor Cortazar in the 17th century when he traveled from Salta to Cachi. While the official road was built between 1928 and 1931 by the church, it was already an important trade route for the Incans – we even saw some ruins of old shelters for the Incan mailmen along the way. We started climbing in the bus at the start of the route which was called the Pie de la Cuesta, or the foot of the hill, and ended at the route’s highest point, the Piedra del Molino, at 3457 meters above sea level. The name Piedra del Molino means ‘millstone,’ and the spot was named for a mysterious heavy granite stone that was found there, which was supposedly used for grinding grain. We also saw a little chapel which was built for San Rafael.

Eventually we passed the entrance sign for the 650 square kilometer Parque Nacional Los Cardones where we made a quick stop for a walk around. In this park there are at least 300 different types of cactus, which can only grow at specific altitudes, typically around 2,000 meters. In the park, at 2871 meters above sea level, the cacti relies on its lucky seed landing beneath a plant, in this park the creosote bush, which can offer shade and protection for the first few years of its existence. Out of the 80,000 seeds from each prickly cacti fruit just 1 germinates. The cactus will grow 1-7 centimeters per year (dependent on type) and can range in height from just 5 cm to a huge 10 meters tall.

While much of their growth is vertical, cacti can store water in their tissues, thus growing fat in the summer as their ribs broaden. Storing water is extremely important in the desert environment, and cacti have many techniques which help them maintain water. For instance, typical tree leaves on cacti have evolved into thorns to defend the plant, and moreover, the reduced surface area leads to low water loss through transpiration. Cacti skin also has a thick waxy coating which prevents water loss and two types of roots designed to capture water; surface roots which capture water from humidity, and long “tube” roots which can reach underground water sources.

These water saving techniques, along with the food-producing photosynthesis preformed by their green stems (which look like their trunks) helps the cacti live a long time, up to 500 years old. Nevertheless, they are still quite useful and sometimes cut down (though not in the park) for their pulp; their skin, spines, wood and pulp can be drunk. When the cacti die naturally they turn to wood which can be used in art or construction. Later we’d see an example of their use in building!

There was a second stop around the park for more photos (and to buy some of the yummy local canned fruits and dried sweet goodies) and a chance to see some ruins of a pukara or ancient fortress. Right outside of Cachi we stopped for filling goat curry lunch before walking to the center.

The little town of Cachi (just 5,500 people) has a name with an interesting history. Many of people living in Cachi are descendent of the Diaguita people, who were strongly influenced by the Quechuan-speaking Incas. Because the word “Cachi” means “salt” in Quechuan it is thought that the name might have been given by natives who believed the snow on top of a nearby mountain was salt or reminded them of salt. An alternative entomology hypothesizes that the town’s name could mean “silent stone” instead. (I didn’t see many stones… everything was cactus wood and adobe!)

Colin and I walked to the central plaza, where there was an Indigenous woman singing and banging a drum in a repetitive beat which we couldn’t get out of our heads. We also took a peak into the Museo Arqueologico Pio Pablo Diaz, but it was pretty small to pay for going inside. Instead we explored a nearby church which had a roof made entirely of cactus wood. That was the building I mentioned earlier! On our way back to the bus, we realized we were a bit lost on where to meet the group – a woman had interrupted our guide when he was explaining in English, and he forgot to continue. We assumed we were meeting where we had been dropped off, which wasn’t the case. Thankfully Cachi is such a small town that even with a delay we found our group in no time.

Soon back in Salta, we spent the next morning at the post office trying to mail a box with some of our things back to my Mom in Florida. It took ages because of our limited Spanish and because the post office didn’t sell boxes or packing material… but we got everything sent and were on our way to the next city!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment