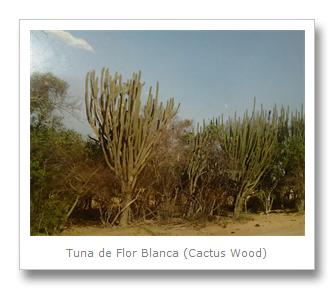

On Wednesday, October 2nd we headed up to the Chaco – just after the Gran Chaco Rally, a racing event, had taken place. We got our first glimpse of the Dry Chaco landscape on the way to Filadelfia. After leaving Asuncion on a 6:00 am bus (and sleeping on the way out of the city) we started heading north and the scenery began to change. We began to see less and less water and green leaves as we transitioned from wet to dry Chaco, and more tall cacti ‘trees’ instead. There were trees which looked very dense with sharp thorns all over them, which is why this area of the world is often called “the impenetrable forest” – some of it is just impossible to walk through without getting stuck with thorns or hurt, especially because the sandy soil floor is covered with sharp bromeliads and different types of sprawling cacti as well. Likewise this area is rough due to its extremely high temperature – it regularly gets above 45–48 degrees Celsius here or more than 113-118 degrees Fahrenheit! This area is so rough the Paraguayans didn’t believe anyone but the indigenous could live in this area, but they were willing to sell some of the dusty land to the Mennonite refugees so they could give it a try.

Colin and I had a couch surf for our time in Filadelfia, with a woman named Demaris. Her family were descended from Mennonite refugees and we were excited to learn about the history and culture from her! She suggested we wait at the Hotel Florida in town until she was able to meet us. We were so glad for this suggestion! Once the bus finally arrived around 3:00 pm (yes, that’s a 9 hour bus journey!) we were let off in front of the Hotel Florida and quickly stored our bags inside. They didn’t mind – we promptly sat down for a nice lunch of chicken and pasta in their restaurant with a big bottle of water to cool us down. (It must have been around 38 C / 100 F degrees outside.) The Hotel Florida’s hospitality was great – they let us use their WIFI and answered our questions about future bus times. This is a place of refuge in Filadelfia for sure!

Once we had finished our lunch we decided to take a walk through the gardens we had seen near the tourist information center across the street. We checked out the tourist center as well, but we found out it is only open from 7:00 am to 11:00 am in the mornings… must be too hot later on! We planned to come back the next morning and just relax for the moment looking around the gardens.

We also saw a couple of cats which must have been twins (otherwise there’s something strange going on!) – they froze when they saw us, seemingly preoccupied with something. Colin spotted what the secret was. The cat under the bush had gotten ahold of a small snake and had bitten its head off! We managed to get a picture of the headless snake after the cat ran away while we were investigating.

Demaris met us in the evening and brought us to her place. We had a nice talk over some sandwiches and terere (mate with cold water and ice instead of hot water and equally as bitter as mate!) she generously made for us and found out tons about the Mennonites, but I’ll explain the details of what we learned within my writing about the Mennonite museum the next morning.

The morning of October 3rd, we first spoke with Gati in the tourist information office. We had tons of questions for her. Our first questions were about rental cars – could she help us call around and figure out how much it would cost us to drive up to National Park Defensores del Chaco or out to National Park Teniente Agripino Enciso.

The only car rental company Plus Automotores in the area gave us their prices:

200,000 Guarani per day (/4500 G to the USD = $45 USD per day)

+ 2500 G per kilometer, after 80 kilometer limit is up

Defensores del Chaco is a 440 kilometer round trip from Filadelfia

440 kilometers – 80 included kilometers = 360 kilometers x 2500 G = 900,000 Guarani/4500 = $200 USD not including gas

It costs about 440,000 G to fill up after driving 440 kilometers (you have to return the car with a full tank,) plus an additional tank for the actual drive so 440,000 x 2 = 880,000 G = $195 USD in gas costs

$200 USD + $195 USD = $395 USD total cost for a ONE DAY CAR RENTAL.

Don’t plan on renting a car to go to Defensores del Chaco, especially not from Filadelfia, unless you have a large group of people. It will cost you at least $400 USD to get there!

After calculating out that a rental car to get quite far away was really expensive, Colin and I decided to take Gati’s advice and see a great example of dry Chaco much closer to the city – Flor de Chaco. She made us a reservation to go there later in the day, then led us around the local museums. The Jakob Unger museum showed us animals and plant life in the dry Chaco – as well as artifacts from native indigenous groups.

The indigenous used the word “Chaco” to describe this region for its abundance of animals – “Chaco” means “hunting ground.” The variety of animals in this region is quite spectacular as the “impenetrable forest” often made hunting them quite difficult. There are many different rodents, rabbits, and world's highest diversity of armadillos in the Chaco – including the pink fairy armadillo which has only ever been found in the Chaco. These creatures provide lots of food for the numerous different birds of prey (crowned solitary eagles, owls) and big cats (jaguars, pumas, ocelots, jaguarundis) the region supports.

My favorite cat is called Geoffrey’s cat which is quite a small wild cat – it isn’t any bigger than a domestic cat! Nevertheless it is covered in black spots making it look similar to a miniature jaguar. This cat sometimes stands up on its hind legs (like a meerkat) to see the environment around it. They are so cute, you really could forget they are wild.

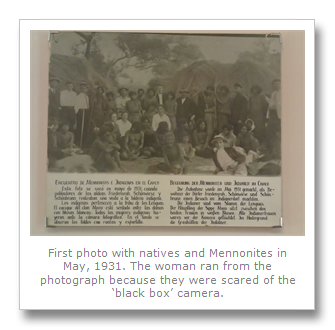

This “hunting ground” around Filadelfia originally had 500 Northern Lingua people living in it, but eventually the indigenous population grew as more natives came –or were brought– out of the bush and into the city. Colin and I watched an example of this transformation in a movie called Reconciliation. This movie tells the story of a group of indigenous Ayoreo people who had been transformed into Christian missionaries by Protestants.

On December 27th, 1986, the Protestants arranged for the Ayoreo missionaries they had converted to go into the Paraguayan Chaco bush to look for the semi-nomadic Totobiegosode. The Totobiegosode are actually an indigenous sub-group of the Ayoreo people, but they had become traditional enemies of the Ayoreo. It wasn’t easy for the new or old missionaries to convince various tribes to join their religion – most couldn’t understand “…how their chief ‘Jesus’ could be a real or true chief when he hadn’t killed any enemies.” The Ayoreo approached the Totobiegosode shaking rattles and yelling they were there for peaceful reasons, but their efforts weren’t easy. Half a dozen Ayoreo died trying to bring the Totobiegosode to their religious beliefs (they were killed by the Totobiegosode who didn’t trust them) and a large amount of the Totobiegosode died once they were brought to the mission and converted due to their inability to cope with disease. No, this wasn’t 1586… this was just 27 years ago.

One of the Totobiegosode women who died at that time was their shaman, a medicine woman who diagnosed by determining which ancestor spirit had power over the illness. When we were in Asuncion later Colin told me that the group of indigenous people our hostel owners were hosting while we were there were two of the last shaman alive in Paraguay. They had only come out of the bush and learned of the existence of the modern world in the last 30 or so years!

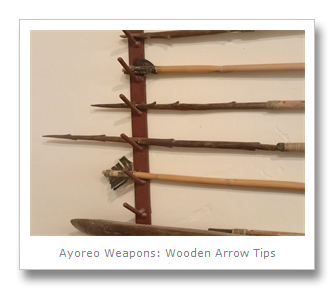

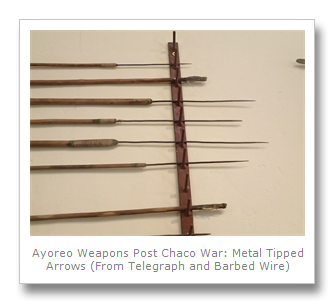

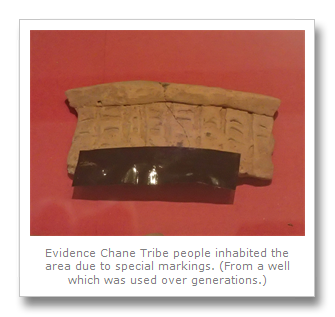

We continued into the following room which displayed objects from the different indigenous tribes in and around Filadelfia. Here are some of things we saw:

We also saw crafts made by the Ache people. Interestingly, one of the four Ache subgroups, has been known to engage in cannibalism, but all the Ache groups used magic as part of their religious beliefs:

These mysteries, along with numerous unexcavated artifact sites, will remain mysteries until the level of care about history and culture in the Chaco is raised to a developed level. We were told at the museum that sites around Filadelfia have not been released to the Paraguayan government because of their poor skills at excavation – which have included grabbing hundreds and thousands of years old objects out of the ground and dumping them as trash. The items shown below are from sites ‘hidden’ from the Paraguayan government’s prying fingers:

There were another couple of rooms that were dedicated to different trees living in the Chaco region. The Quebracho Colorado or “ax-breaker” tree (as its known because of the unbreakable nature of its wood) is used for producing an extract used for tanning leather called tannin. The wood is made into chips which are boiled in order to get this extract which gives the leather a beautiful reddish-brown color. There is an industrial plant in Filadelfia we passed by which used to produce the once valuable tannin years ago – more eco-friendly methods are used now.

Another interesting tree for its strange greenish color is the Palo Santo tree (‘holy wood’) used in furniture-making and for the making of durable wooden posts because of its resistance to weather elements. There were even examples of the cacti and wood that could be gathered from them!

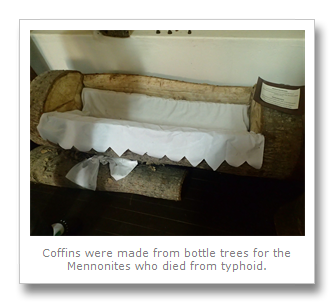

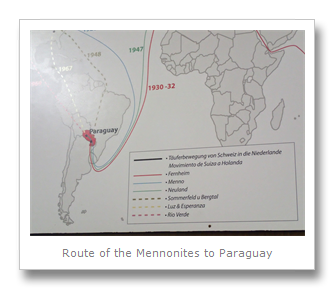

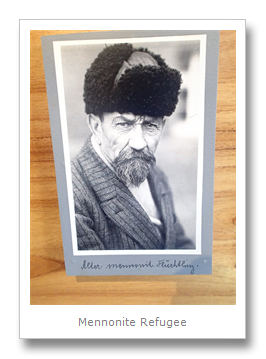

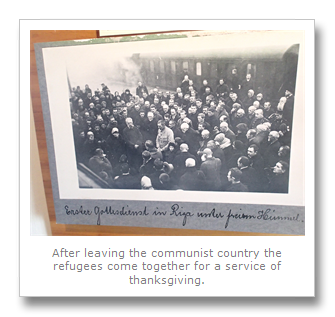

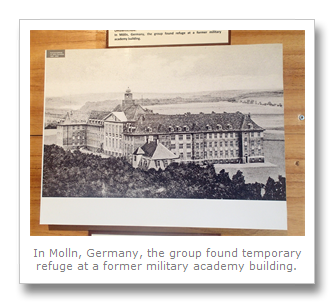

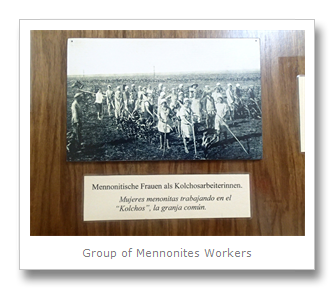

Next we were led into a room, then a house, dedicated to the story of the Mennonites who began the colony Fernheim (meaning “distant home”) in the area of Filadelfia. These rooms along with the documentary “Heimat fur Heimatlose” (meaning “Home for the Homeless”) really gave us a good picture of the Mennonite experience in the Chaco.

Originally the Mennonites allotted 40 acres of land per family. The Mennonite Central Committee also helped buy equipment for the settlers, on credit so they had to eventually pay back the financing. The Mennonite cooperative ran everything – and still seems to run everything. There are cooperative newspapers, post office, loans, pharmacy, supermarket, hospital, etc. There are three different churches however, the Mennonite, Mennonite Brethren, and Evangelical Mennonite Brethren.

The Mennonites successfully figured out how to live in the Chaco and develop it for cattle farming through their experimental farm initiative. When they initially arrived, their cows wouldn’t eat any of the grass in the area- finding it too bitter. This process helped them to figure out what type of grass cows will eat as well as which types would grow in the desert, dry Chaco climate. They also experimented with what types of cows could be raised easiest in the climate.As the Mennonites built up a stable communities based on “faith, unity, and work” with industry and jobs, various indigenous tribal groups (thousands of people) started coming from the Chaco bush to Filadelfia because they could find simple work (working in fields or producing cotton and peanut oil in the industrial plant) and goods and an easier way of life. One native even said “once you taste bread, you will never go back to the bush” after his experience. For the indigenous people this was a dramatic change in lifestyle in just 50 years time. They went from educating children by example to educating children in schools. Tribes still maintain their common parenting culture of “making suggestions” or “counseling” children on their options rather than “making demands,” and many indigenous children end up not going to school or getting into violence at school.

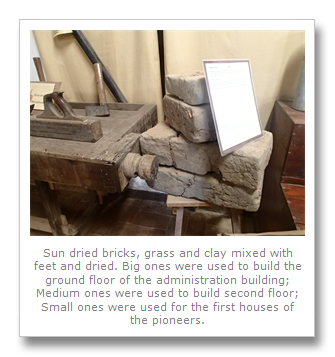

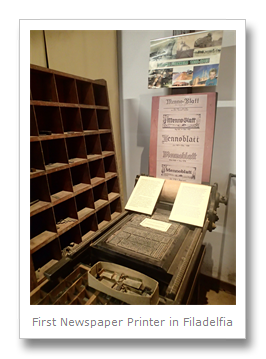

We saw many different objects from the first Mennonite settlers throughout the museum as we read and learned about their story. Heavy clothes from Russia, the first tools bought with community money, the first newspaper printer in Filadelfia… they even had an abacus that was used until 1970 when the colony got its first calculators.

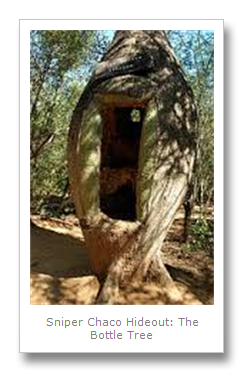

Upstairs there were some items from the Chaco War, since it took place around Filadelfia. The Chaco was mostly ignored in the colonial era, as people believed it to be an unlivable area with only indigenous people. Starting in 1890 the first missionaries, cattle ranchers, and skin traders entered the Chaco. When the oil was found near Villa Montes, Bolivia was searching for an access to the Rio Paraguay to secure transportation. In fact, when Bolivia set military outposts to reclaim the territory in 1925, the Paraguay answered with similar activities. In 1932, the first confrontations occurred which eventually escalated into the Chaco War. The Mennonites were left out of the war – in fact, only 1 was killed by accident – due to their anti-fighting beliefs.

Another good result (besides few of their own peoples’ lives lost) from the Mennonites’ belief of non-violence was the building of the Trans-Chaco Highway. Mennonites in the United States did not want to participate in the Vietnam War. They didn’t mind suffering in some way, but they did not want to fight and kill. Therefore they proposed they could help give the USA a good name in Paraguay by doing some “community service” hours in the country. (Perhaps this history resulted in Paraguay being such a popular place for the Peace Corp tradition?) Therefore, American Mennonites ended up building the Trans-Chaco Highway helping other Mennonites and sticking to their beliefs of non-violence.

After the museums (it was only 11:00 am!) we decided to go see Markus at Plus Automotores for our rental car. While it was too ridiculous to take the car to Defensores, we thought we could make a good day by going to see the Tagua Project in Toledo, Fort Toledo, and the private reserve of Flor de Chaco – a good example of dry Chaco environment. A quick trip later to get my driving license we had our first rental car rented – ever! The first stop was the cooperative grocery store to pick up some bread, chicken and fruits for the drive. Next we took the car out on a scenic drive (including many animal stops) through the dry Chaco landscape.

One of the first animals we saw was a beautifully colored group of Ibis birds called Buff-necked Ibis. They were the biggest Ibis we had ever seen, about the size of a house cat, and had bright yellow throats. As we could clearly see, these Ibis are common in grasslands throughout South America. Colin had seen one of these stuffed at the museum earlier, so he was really glad to catch a glimpse of some in the wild!

Eventually we arrived at the Tagua Project – a project run in part by the San Diego Zoo in the United States. It was around the time siesta started (all the time… just kidding, 12:00 noon!) so we had to beep the horn a couple times from beyond the locked gate to get someone’s attention (and to keep us away from the huge guard dog’s teeth) and shortly a keeper of the project came out to lead us around.

He (with the guard dog following us) took us to see 3 different types of peccary. There were over 150 peccary at the Tagua Project, divided by cages into their different species. They didn’t look like “pigs” or “boars” in the way you’d imagine. They were all quite dark and hairy, and their hair stood up on end like a full-body mohawk when they were angry or nervous. Quite strange. (Colin’s Edit: All of the peccary smelt really, really bad!).

The first group of peccary we saw were collared peccary, which seemed very curious about us but slightly nervous. When they saw us they stuck their little noses through the cage and tried to figure us out, sniffing at us. When they were given water and food they butted each other around a little, but just lightly, and they seemed decently well-behaved for pigs.

The second group of peccary were really scary! These guys were called the white-lipped peccary, and they were extremely aggressive with each other and with us. They were constantly fighting each other, and whenever we came slightly near their cage they would throw themselves up against it in anger like wrestlers and make loud grunting noises. They even sprayed mud out at us! Our guide told us this behavior is a natural adaptation for these peccary. There was a second set of these guys in cages behind the initial mating pair we saw and when I ventured over to them their eyes bulged. I started hearing this strange noise I couldn’t identify – it sounded like a plastic water bottle being crunched sharply and loudly. This sound was apparently the peccary’s teeth, snapping together in anger at the sight of us. If the Mafia ever used pigs to tear anyone apart, these guys were surely for the job! In fact, the owner of the project, Jakob Unger, is quoted as saying: “…if you encounter a herd of white-lipped peccary, which can number up to 200, you had better be able to run fast or fly!”

The Chacoan Peccary is also called the “tagua,” and it is the largest of the three types of peccary in the project. Scientists believed this species was extinct for 15,000 years until 1975 when it was spotted by Dr. Ralph Wetzel. (See this LA Times article.) This peccary were really freaked by us being around and they reminded me of scared cows who just stand in the field and stare at you for ages.

The three of us (plus dog) went on a walk a bit away from the peccary to see ‘Fort Toledo,’ which consisted of some old war trenches and the location of some of the Chaco War battles. While the Chaco War didn’t quite reach Filadelfia, in this area there was plenty of fighting, in fact, this location was were the Paraguayans/Guarani started to push the Bolivians back and weaken them. John Gimlette in At The Tomb of the Inflatable Pig (mandatory reading for anyone coming to Paraguay!) tells it best:

“The fort was built by General Belaieff, the anthropologist. He wasn’t the only White Russian on the Paraguayan side; there were sixty others in gold braid. It was a war much to their liking; Major Chirkoff would cut down an entire Bolivian company with his machine-gun and Captain Kassianoff was to die in a magnificent cavalry charge. They are remembered in a popular drink: tereré ruso (tereré with sugar and muddy water). Of course, it’s coincidence that—once again—Kündt, the Russians and the Fernheimers all faced each other across the same battlefield, but it gave Toledo a certain symmetry.

In all other respects the battle was grotesque.

It started with a tiny Bolivian aeroplane straying into small-arms fire. First, the observer jumped out without a parachute, and then the pilot smeared himself across the Paraguayan lines. Both were buried with full honours and the Bolivians sent a wreath and a fly-past. With the funerals over, the killing began.

It lasted two weeks. The Bolivians eventually got just near enough to the Paraguayan trenches to be caught up in the thorns and barbed wire. The Guaranís then finished them off with home-made grenades and bayonets.” (Gimlette, 124)

While Colin and I were standing at the trench our guide pulled out a long snake skin from one of the logs – that stopped us from going inside the trench for photos, for sure! Back to the car…

We enjoyed our chicken sandwiches in the car (with blissful A/C running full blast to avoid the deadly heat) before going back to Filadelfia – we head to drive the opposite way of the colony to get to our next destination: Flor del Chaco. While driving out Colin spotted a few more rhea and a rabbit, and I spotted something that looked quite strange sticking its head out towards us from the bush. It reminded me of my chinchillas I had as pets when I was younger, but more brown and less “fluffy.” It looked almost like a small capybara, but not quite. I’d see it again later at Flor del Chaco…

We managed to get some great photos of a couple of owls perched on the side of the road (our first time seeing owls in the wild and the inspiration for my Paraguayan charm for my collection), and on our way into Flor del Chaco we saw a massive capybara!

After an animal-filled drive there, we pulled into the reserve and met Hugo Stahl, a Christian missionary and the owner of this private dry Chaco reserve. He pulled out a giant hand-drawn map he had made for us before sending us off towards the lake in search of animals. We started on the ‘walking’ trails which provided a closer look at the nature first. The thorns got us everywhere – it wasn’t easy to walk through unless you stuck to the trails, elsewhere you’d end up scratched. Later on we’d both find and extract tiny blood-sucking ticks which had imbedded themselves in our skin from the experience of walking so close to the bush.

Almost immediately upon starting I spotted another one of the strange-looking animals I had seen at the Tagua Project. This time I got a much better look at it. I think it was a Chacoan tuco-tuco! This rodent is similar to a gopher, and they are about a similar size and shape to chinchillas, but with less fluffy hair on their bodies. They create tunnels in the ground and are thus not often seen above the surface unless you really look!

Colin spotted the next animal first, quickly after I saw my own. It was small and extremely quick, shooting itself across the ground before our eyes. Our first armadillo! Armadillos are native to the Americas (related to both sloths and anteaters,) and there are a huge diversity in species from the giant armadillo (150 cm) to the elusive pink fairy armadillo (12 to 15 cm). We saw our little guy pulling at leaves, trying to get some dinner at first but when he spotted our presence he scattered. Not before we got a good look at him though! We believe the one we saw was the ‘Chacoan naked-tailed’ armadillo; it had a small yet soft-looking ‘leathery’ armor shell, hence their name “little armored ones.” In fact, they look so unique the Aztecs called them “turtle-rabbits.”

Midway through our walk we saw a nervous but majestic looking deer. The deer spotted us at the same time and froze for ages (ten minutes), trying to blend in with the dry, brown foliage background, Colin guessed.

As we were walking around we ran into Hugo’s wife, out for her evening walk. What a fantastic place to get your exercise – among the animals and nature every evening. So lucky! Once it started getting dark (after 6:00 pm) we decided to head back to Filadelfia. After a quick stop at Hotel Florida for a snack we went back to Demaris’s place and crashed for the evening. The next morning consisted of returning the rental car, getting our bus tickets sorted out, and having lunch with Demaris in Hotel Florida. (They do a great buffet lunch that half the town seems to come in for!) During lunch she told us about her work in the social sector; since there are no orphanages in the Chaco, children had to be placed directly with foster families. Our bus for that afternoon was back to Asuncion, as through the capital was the quickest way to get to Encarnacion and the Jesuit Ruins.

Now Colin will take over from here!

Francesca

No comments:

Post a Comment