On the 16th September we made a hair-raising walk into Paraguay across a stupid dilapidated bridge which had a wire grate as a walkway (complete with frightening dips and bulges as we walked on it carrying the full weight of our rucksacks – not to mention holes big enough to fall through, and down, 20 meters to the caiman, piranha and trash-infested Rio Pilcomayo below), and we found ourselves in another world. This new world was populated by poverty-stricken indigenous peoples, looking more at home in the Andes of Peru than as a welcoming party to travelers coming from Argentina. These vendors looked too astonished to see two backpackers pass this way, even in 2013, and gawped as we moved quickly past and towards the bus stand, all the time ignoring the hustle and bustle of the money changers, los cambios, who would probably have skinned our budget alive if we had not realized that the bus would surely accept Argentine pesos.

We bounced around on a decrepit bus seemingly held together by glue while brown-skinned women eyed me suspiciously. Francesca can get away with it with her skin tone. We passed the Rio Paraguay over a huge bridge connecting South with North, just as that river disconnects Paraguay cleanly down the middle, creating two very distinct halves, East and West.

The East of Paraguay is the Atlantic rainforest, the humid Oriental. It is here, where, surrounded by the rivers Paraguay and Parana, most of the 6 million inhabitants live. Although there is little to no infrastructure for the backpacking tourist in the country, the East is where most reserves and National Parks are found in Paraguay.

The West, el Chaco; a Guarani word for the ‘hunting grounds’, is a 647,500 km squared sprawling desert. Covered in cacti scrub and dense thorny under brush, the conquistadores called this place el impenetrable. We just heard what must surely be a rumor from the Chaco about a local Indian man who went missing there recently. They found him, eviscerated by a giant Anteater, locked in its death-grip, his knife in its side, both dead.

Sitting at the bottom of the country and right in the middle of these two worlds is the capital, Asuncion. Like any other third word city, it sits beneath a dense cloud of smog, and is purportedly one of the strangest cities in the world. A mix of architecture is borne from the multitude of immigrant groups who have settled here over the centuries. English, Spanish, Italian, German; many came to this part of the world to either find a fortune, or escape judgment. Everyone from crazy Scottish engineers and big game hunters, to Nazis like Eichmann and Mengele came through here. Only those that turned their hand to farming like the Mennonites – a former rag-tag band of disposed Anabaptists turned cattle millionaires – have succeeded. Many others simply went mad.

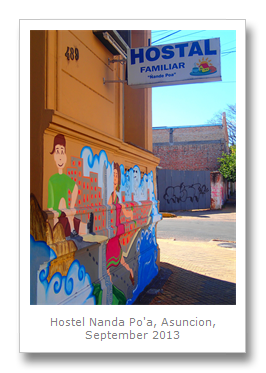

Paraguay is little known on the backpacker circuit – possibly for good reasons – but we did know where our hostel was. We saw a lone ATM sitting unnervingly atop a pedestal in the middle of the bus station. It provided us with some local currency – Guarani. Named after one of the more friendly Indian tribes in the region (they teamed up with the Jesuits to help ensure their survival, and to get help exterminating their enemies), the heavily inflated currency is one that has way too many zeros on each note. Withdraw $US200 and you are a Guarani millionaire. Guarani is also the language of most Paraguayans, with the average Paraguayan more likely to speak Guarani than even Spanish – it is the only official language left that is indigenous.

We arrived at our hostel after taking an inexpensive metered taxi (40,000 Guarani is less than ten bucks for a half hour ride). The hostels, the food and the transport were all much cheaper in Paraguay than South of the border, and it felt good to be in a new country again. There was only one other guest at the hostel which was run by a Uruguayan family from Salto, where we had visited the thermal baths. They had decided to pick up sticks and settle in Asuncion (for reasons past understanding), and the family were extremely helpful, sweet and pleasant.

After a days rest (in which time we agreed that we needed more information on the logistics of visiting the National Parks we wanted to see) we went out to meet some American Peace Corps types in a long-running pub in the centro district called The Britannia.

We met in the smoky and dimly lit pub and there were half a dozen Peace Corps volunteers all making the most of a half-price happy hour offer on food. Washing it all down with bad house wine was the order of the day – and we stayed for an hour or so to chat and learn a little about the corps. and why young, bright twenty-somethings would give it all up in the USA for pittance pay in Paraguay.

After applying for the Peace Corps you are either accepted or not, and they then tell you which country you have been assigned to. Paraguay is apparently considered a bit of a catch, as it is stable, cheap, and a lot safer than some of the other toilets you might be sent to (re: Mexico or Sierra Leone). You work in a particular field, for example, health education, or soil conservation, and you are given a sector, or location, and you start your project with whatever resources you can muster. It teaches the volunteer about how to think for themselves and put together something worthwhile without an employer/employee mindset, and it helps the locals whilst showing them that America is not just a great white Satan come to steal all their oil and babies.

Many of the volunteers had to source their own phones, apartments, means of travel, etc. on a peon’s wage, but they all seemed happy that they signed up for 2 years. It seemed like a racket to me, but straight from the horses mouth: they liked the work, felt like they were making a difference and learning a lot, enjoyed Paraguay and the locals they worked with. They did all admit to looking forward to getting home though, so I doubt any of them will stay, although it happens. The Peace Corps is by no means a religious group, so all power to them – they are invited by the locals and the arrangement seems to be beneficial for everyone involved. One guy worked educating the locals in healthcare, alongside expert doctors (one of which had won the Mister Paraguay bodybuilder competition). Hard not to agree with that.

We left the pub at the end of the evening with a deeper understanding of the Peace Corps but could not muster any information pertaining to National Parks – none of the Peace Corps volunteers had been to them – a fact that would hint at what we would come to learn about the inaccessibility of the National Parks and reserves in Paraguay.

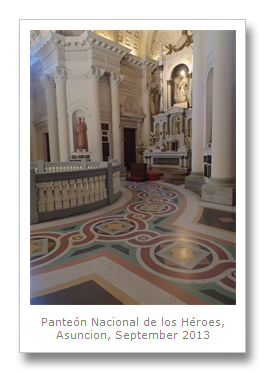

The next day, the 18th September, we headed out into the city center to visit some attractions, the first of which was the Panteón Nacional de los Héroes. To say Paraguay has any heroes is, perhaps, an overstatement. At least there are none buried in the Panteón, and it is this that is reflected in almost every place we visited in Asuncion. National flags fly everywhere, from banks, schools and homes – and, more importantly, there are the maps.

The maps of Paraguay, in Paraguay, are typically hundreds of years old. They show Paraguay not as it is now (a landlocked no-mark with few opportunities) but as a South American powerhouse that once rivaled Brazil in size. The maps are a reminder to Paraguayans that the land that was once theirs has been stolen by their brutish and bullying neighbors.

Paraguay’s first ruler was dictator José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia who ruled from 1814 to 1840. He defeated a plot to overthrow him, and was quite mad, and after he died, his nephew Carlos Lopez stepped up to be the second dictator. Lopez formally abolished slavery and torture in his rule, but unfortunately he was a pretty wicked man himself and a glutton. He died in 1862 when his eldest son, Francisco Solano Lopez took charge. He was a power mad Napoleon fetishist who took an Irish whore as his mistress, and travelled Europe seeking the trappings of state whilst being mocked behind his back by the European leaders. None of his Paraguayan contemporaries accepted his mistress, and they were bitter about this the whole time he was dictator-in-chief. In 1864 Lopez junior made the huge mistake of a land grab in present day Uruguay, to gain control of the Rio de la Plata area, which sparked the War of the Triple Alliance. Paraguay had it’s ass spanked and lost up to 90% of it’s fighting age men. Lopez was killed by Brazilian soldiers when he refused to surrender.

It is Lopez and his generals who now sit in the Panteón, and it is debated, hotly, whether he is a champion for smaller nations fighting their aggressive neighbors, or whether he was a fascist with a Napoleon complex who led his country to a huge defeat and near extinction. I think these dictators have long exploited the South American poor and downtrodden and still do even today, but in the disguise of a democratic government. Which leads us to our next visit as we headed off to the Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies), the Paraguayan House of Representatives. We were waved away from the old building towards a new glass building: ‘This can’t be right’, we thought. It was the official government entrance and people were being subjected to security checks. Damn. We forgot our passports. ‘No matter, come in, we will show you around!’.

The first part of our tour, in broken English by a guide called Carlos, saw us enter the oldest part of the building. Originally built by Jesuits in 1588 as a temple, this building had been a jack of all trades – a school, a mission, a hospital and a military building. Recent excavations revealed many old objects such as cannon balls, kitchenware and religious artifacts. The elderly guide who runs this part of the building told us that the statue of the saint in the room was Saint Roque González de Santa Cruz. Apparently he was killed by an Indian chief and was set on fire. His heart was found unscathed by the fire, a miracle! We call bs on that though as we visited the church where ‘his heart’ and the weapon that killed him is supposed to be in the Chapel of the Martyrs attached to Colegio Cristo Rey – it looked like a pig’s heart to us.

Walking from the old building to the newer building, our guide explained that this part of the building was paid for by the Chinese. Our best guess as we tried to pick through the Paraguayan smokescreen of half-truths and lack of information is that the Chinese are huge contributors to Paraguay as they benefit massively from the natural resources that the country offers and they need so desperately.

Extraordinarily, the congress was in session so we could not see inside the chamber, but we did get to walk through the corridors of power briefly and watch all the staff working and dealing away.

Back outside we walked across the plaza and found a monument to a large tree breaking free from its chains. Someone had defaced the plaque though, so you can make up your own mind what this monument stands for. To get out of the heat, we headed quickly to El Cabildo, the main congress building of olden times now a cultural center and museum.

The first room was dedicated to colonial art and contained mostly religious carvings and sculptures. Most of them had come from the labors of the Guarani workers that the Jesuit drafted into their missions. The next room had some indigenous crafts and clothes, including some cool-looking shamans feathered headpieces. An impressive canoe from one piece of tree trunk stood in a corner. Most of the collection was from the Chamacoco tribe who have only just struggled through the 20th Century barely alive in the Chaco. Enslaved by Jesuits, the army and tannin companies, they have been living on next to nothing since they had the misfortune of meeting a European. In 2009 they, along with other tribes, were given free land (with no property on it) which many consider to just encourage a victim attitude in the communities.

The next room was filled with colonial kids’ toys like rocking horses, and the rest of the floor had paintings of varying interest. The last room on the ground floor was dedicated to the Chaco War fought between Paraguay and Bolivia between 1932 and 1935. This war made soldiers out of the men and tribes who were remaining after the War of the Triple Alliance. Tribes like the Chamacoco who were sent to fight over what was essentially just a land grab for oil rights. After three years of fighting and over 100,000 deaths nothing particularly changed in terms of the border, and the two landlocked countries were faced with the reality that they had fought a long and hard campaign for a semi-arid desert devoid of oil or gas. The Chaco War, although seemingly ending in truce and stalemate, was more successful for Paraguay than Bolivia. Bolivians led a coup against their government in the fifties as a direct result, and Paraguay gained most land officially in the subsequent treaty. In fact, it was only last year that oil was discovered in the Paraguayan Chaco – and now a potential environmental disaster is waiting to happen in this bio-diverse and fragile ecosystem. There is a propaganda poster on display in the exhibit that shows a soldier being read an official document on the battlefield that says after the war he has a contract to go work in the Bolivian mines. This confronts the soldier and asks him what he is really fighting for.

After we left this room, we found a small old voting room from when the building used to be a government seat. Francesca fielded some questions and we headed upstairs. On the way we found surely the most difficult game to play at Christmas – ‘Icons of Paraguay’, for ages between 3 and 90 years.

Upstairs was a dedicated exhibit to the music of Paraguay. There were famous guitarists, harp players (Paraguay’s national instrument) and clarinet musicians. Instruments and sheet music were everywhere, and the view out of the building (past the slum behind the Cabildo) of the Rio Paraguay was pretty in the sunshine.

We were pretty hungry at this point, so we decided to head to the Lido bar. A Paraguayan institution that has survived numerous dictatorships and decades of economic hardship, the Lido bar is a 1950’s throwback, with the waitresses all wearing a garish orange flight stewardess uniform. They do specialize in Paraguayan food, of course, so we tried our hand at sopa paraguaya, which is basically a corn bread with eggs, manioc and cheese. This and a Russian salad with grilled chicken went down very well. Even though Asuncion was pretty rough, the food was certainly decent.

We made our way to the Casa de la Independencia next, which is where, in 1811 the Paraguayans declared their independence when Spain’s attention was in Europe fighting Napoleon. The building looks like so many other museums we have seen from Rio to Montevideo to Recife to Rosario – full of old junk which is interesting for half hour and no more.

After walking around in this junk store for awhile we headed towards the river. It was such a hot day we took it pretty easy, and we eventually found another cultural center called Manzana de la Rivera opposite the pirate bar (that’s Paraguay!).

The museum inside was pretty cool, with lots of obligatory maps showing Paraguay as a powerhouse a million years ago. It had some of the first sketches of some of the weird and wonderful animals of the region done by Spanish explorers – imagine what a feeling that would be! It had the story of Asuncion too: founded in 1537 as a fort it is one of the oldest continually inhabited areas of South America since the discovery of America by Europe which is why it is often called ‘the mother of cities’.

After a big fire in 1543 the city just kept growing, and it now holds one third of the population of tiny Paraguay. It was in 1562 when Indians sacked and destroyed Buenos Aires that a capital of a new province was set up in Asuncion and its importance was sealed thus creating Paraguay.

Other than the small museum, there was not much else to see here, a small gallery of modern art, a curious old man in a room with loads of VHS tapes about Paraguay that looked really interesting, but no way to play them and no way to put them to digital (he just sat all day drinking mate and smoking!).

We ended our day by heading by the Black Cat hostel and finding out some useful information on the National Parks in the Chaco – namely that there is no infrastructure there anymore, they are abandoned, full of snakes and jaguars and you need a tour to go there definitely. We had a plan to get the local bus there, but maybe it is a bad idea?

The next day, the 19th September we headed out to the Botanical Gardens of Asuncion. After getting furious with bus driver for nearly driving off with me stuck under a tire we got off (without paying), and went into the park. It was another lovely day, and we made it to the museum where they have a great collection of pickled oddities such as a two-headed puppy and a whale eye, and a not so great collection of terribly made animal models that look nothing like the animals they are supposed to represent. And why have they got a model of an African lion there?

After eating our sandwiches and being annoyed by a persistent wasp, we walked around the park for an hour – spotting some rhea behind a fence which we realized was a zoo. We did not go in as we do not want to enter a zoo without researching its treatment of its animals. That might sounds stupid, but in a country where you can buy an armadillo for $US5 and an endangered giant anteater for $US25 from desperate poachers, it is no joke.

After walking around for a bit, we jumped in a cab and headed back to our hostel. On the way we saw the hulk of the Ycuá Bolaños shopping mall which was burned by fire in 2004 where 394 people were killed. On our first walk out on our first night, we had gone to a mall to get food and everyone had been thrown out because of a fire alarm. no wonder they were taking it so seriously!

On the 20th we looked for one museum but realized Google maps had shown it in the completely wrong place! We made our way for a different museum called Museum Dr. Andres Barbero – where anthropologist Branislava Susnik had once lived. An immigrant scientist from Slovenia Susnik eventually set up in the Chaco and Asuncion and worked alongside the tribes there, documenting their lives, languages and rituals. A series of photos of Chamacoco people’s shows one of the few rituals that survived the Jesuit interference.

Groups of men dress up as anapsoro, the gods of the Chamacoco people. These gods supposedly taught man how to live, use tools and perform rituals before they had a big falling out. One god, sympathetic to men taught us how to kill the anapsoro by attacking their ankles! When only one anapsoro survived, called Nemur, he escaped. He almost got caught but used a snail and some magic to create the River Paraguay which separated men from him. The man leading the hunt for Nemur was called Syr, and he shouted across to Nemur ‘You can run, but your destiny is to be alone forever’. Nemur replied ‘You are numerous, but you will always have to follow the words. If you do not, sickness, hunger and enemies will decimate you until you are no more’. Harsh words, Nemur. The gods fell out with us over the death of too many humans during the coming of age ceremonies, one of which was photo-documented by Susnik.

In a series of photos covering Susnik’s time in the Chaco with the tribes, it became a little disturbing how close he seemed to become with some of the very young girls in the pictures. In later photos he seems to be surrounded by children that look suspiciously half-European.

This museum was rescued by Susnik’s photos if that interests you, otherwise I would recommend giving it a miss – nothing is in English and you cannot take photos for some dumb reason or other.

We dipped into the railway museum of Asuncion but it did not look very special for the 5 dollars it would cost to go in so we went to Bolsi instead. Another foodie institution of Paraguay, they specialize in pastas and pizzas and Paraguayan food. We looked for the rabbit curry on the menu but alas it must have been taken off, so we settled for chicken, rice and couscous. Delicious.

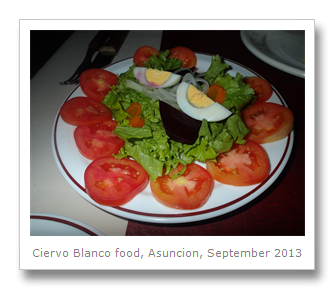

We had nothing else to do in Asuncion that could not be put off until we got back, so we relaxed the rest of the day and the next night we went out to a dinner and folk show called Ciervo Blanco (white deer). The show was supposed to include folk dancing and music but we only got the music because a storm came in from the Chaco – lightning and thunder and the full works for half an hour – a real tropical storm. The venue was under roofing but with a huge outdoor courtyard in which we saw the rain lashing down. All of a sudden we saw huge marbles of ice hailstones come down a Francesca got me worried with talk of tornados! Funnily enough, we found out later that the storm proceeded into Brazil where it did create a tornado which killed two people near Sao Paulo!

We were one of the first people to come to the show, so we got our food really quickly – a platter of sopa paraguaya, meats and cheeses first. While enjoying that, we got a plate of fries, a plate of salad, and then potato salad! We were not sure if it was all for us! Then a small BBQ over appeared next to the table with a large selection of asado meats on it! Delicious lamb, beef, chicken and pork. We ate our food and then they boxed it up to go for the next day!

Entertainment came from a harp player called Martin Portillo. He was world class and I have never seen a harp played before especially not like that! He played all sorts of Paraguayan styles of music, and other South American styles. As he was fleshing out for the rained-off dancers he also got to his Beatles repertoire, playing loads of their songs on the harp! Cool!

Next up was a cheesy and unlikely band that took requests. They played happy birthday in Guarani twice, read out messages from the crowd, and played music from all over the place. They then wheeled out the strangest thing ever – a little accordion-playing 10 year old kid who was dressed like Justin Bieber, but who looked like Baron Von Greenback with the attitude of a lechery 70 year old tango dancer. He was really good and they said he even sold out the theatre in Asuncion when he played there, but it was disturbing – like watching a car crash that you cannot look way from. Surely the oddest thing I’ve seen on the trip so far – and I’m sure that kid is a cocaine riddled mess waiting to happen.

Ciervo Blanco was an excellent night out, despite the lack of dancing (we wanted to catch the bottle dance, where women dance with bottles on their heads!). Maybe next time…

The next day we left Asuncion with sore throats from all the pollution, looking forward to seeing some National Parks on our own, after finding a disappointing lack of information about them. Our hostel owner helped us set up a taxi and gave us bus times and we headed to Concepcion on the 22nd September.

No comments:

Post a Comment