The Rio Paraguay runs for 1629 miles from Brazil to Northern Argentina, where it meets the Rio Parana and continues all the way to the coast and to Buenos Aires. We were heading North following these rivers upstream as it was technically still winter in the Southern hemisphere, even though the current hot spell places the temperature at well above 32C (90F). The plan was to head to Paraguay first, and then come back to go to the south of Argentina when the snows melt and the trails, passes and roads become more accessible again. The confluence of the Rio Paraguay and Rio Parana is 20 miles North of our next destination, which was Corrientes. Its name translates to Currents, after the swirling and difficult to navigate waters of the river and is the state capital of Corrientes state. It is also 350 miles North of of our last destination, the state capital of Santa Fe, and so we took an overnight bus to get there.

On the 8th September we arrived in Corrientes at about 6am after a not-so-bad overnight bus journey from Santa Fe. Argentinian buses are pretty good – comfortable with reclining chairs, and we even got free water, a hot meal thrown in, and a glass of champagne each! Nice treatment!

Our couchsurfing host in Corrientes was called Jeronimo, a private school teacher with an apartment overlooking the river. He kindly welcomed us into his home and, because it was still so early, Francesca and I went straight to bed after the tiring bus journey.

The rest of that day and the next were relaxing days where we rested and caught up on admin, laundry and planning our trip and some websites we are building. By now the hot spell had become ridiculous and it was difficult to walk around for more than 10 minutes at a time outside. The annoying siesta was now making much more sense as the burning midday sun makes it impossible to be productive. One major win, however, was finding a money changer at the dolar blue rate near the pedestrian zone of town (message us for details), and buying some groceries to save some money.

There were numerous tour agencies dotted around town, and a helpful tourist information office on the 25 de mayo street. I dutifully visited a handful of these agencies to see about tours to three of the National Parks in the area, but they ere either too expensive (in the case of Ibera), too inaccessible (in the case of Mburucuyá) or in the wrong province (Gran Chaco). Gran Chaco National Park looked like our best bet, but we would have to travel from Corrientes’ sister city across the Rio Parana, called Resistencia.

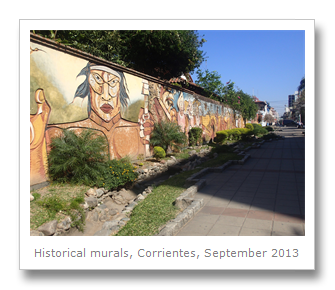

On the 20th September we finally got out of the apartment and headed into town. We walked along Mendoza street admiring the historic murals commissioned by the city to tell the story of Corrientes. The first is called The Great Mural and depicts the Guarani natives meeting the Europeans and being inducted into forced labor and religious servitude, along with the treatment of African slaves. There are many important stories the various murals tell and they are to be found all over the city. They are carved directly from the wall on which they appear. In the heat of a sunny day they looked pretty cool, especially on Mendoza as this is a nice little pedestrian street with many trees and flowers and water features (which were turned off – all water features in South America are permanently turned off).

There are many trees in this part of the world that are very pretty – the pink lapacho, the purple jacaranda and the orange-red ceibo. All of these were found along the streets of the city, and we also stumbled upon a little square called 25 de Mayo Plaza. There is a large (obligatory) statue of San Martin on horseback here surrounded by brightly painted silver canons that were used in the independence wars and now guard the statue as a fence.

We went to check out the Paraguayan Consulate in Corrientes, which looks like an apartment block (because it is). We were told by the dopey looking mate drinking doorman that the consulate closed at midday, so we figured we would try and do it in Formosa or Clorinda on the border. If you do try here, go at 7am or 8am otherwise you will not get it done!

We walked down the street and walked alongside the Rio Parana on Avenida General San Martin, as it was recommended by our couchsurfing host. There were some broken down hulks left on the river that barely floated anymore, and the day was so bright the air was filled with white light making visibility a little unclear. The river looked nice, and we could see buildings on the other side in the province of Chaco (to the West). I preferred the views in Rosario myself.

We did see a big casino here, but not as big as the one in Rosario apparently – the Hotel Pullman Rosario City Center is the biggest casino in South America. Seems like gambling is a big thing in this area.

We then came across our first cultural stop of the day, the Museo Histórico de Corrientes which had its opening hours on one wall indicating it should be open, and the dreaded cerrado (closed) sign on the door. Undaunted we shouted into the guard who ignored us twice, and then was forced to get someone who worked there, who came and told us to enter. The door was locked so they went looking for a key. Another guy turned up and opened the door – apparently they were open, but no-one had bothered to open up. Guess they do not get many visitors.

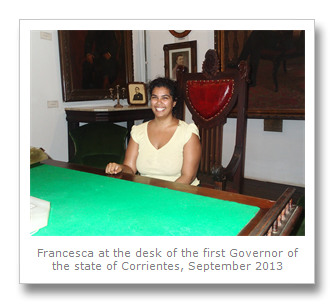

Our guide spoke no English but was quite happy to follow us around and natter away in Spanish the whole. time. we. were. there! We learnt absolutely nothing here, but it was cool to see some old tat, mostly old flags and banners. They also had a bunch of old furniture and we got to pose behind the first Governor’s desk on his old chair! Not exactly eco-tourism at its height, but there you go. We made our escape after a short while, with heads throbbing from the incessant Spanish questions about football, the Falklands Conflict, and why we are travelling for two years.

We walked past Teatro Juan de Vera next, and a nice kindly old man outside told us it would be fine to go in and take some photos of the auditorium, and a mean nasty young man inside told us he wouldn’t switch on the lights and what were we doing there anyway?

Francesca wanted to see some of the local folkloric dance they have here called Chamamé, but the theatre was not showing any this week. Maybe on the way back through after Paraguay we can try again…

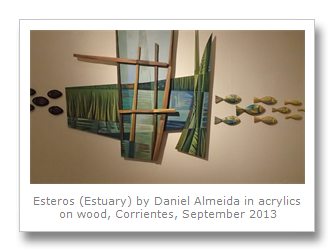

The small but cool Museo de Bellas Artes was next on our list. A helpful lady invited us in, and we wandered around the various Argentine and Spanish paintings. There was an old style library here, and even a modern exhibition of some nature-inspired paintings by Josa Kura. My favorite was the series of four paintings based on the four classical elements (water, air, fire and earth). The lady even told us about a Chamamé bar where they had the dances – maybe we would check that one out?

It was so hot by now we were glad that the few hours we had planned to be outside was almost at an end. We took a look at the Convento de San Francisco, but it was completely closed up. Broken windows and a serious need of a paint job belied all of the guidebook recommendations – although it did look a little like the Adams Family house. We called it a day and headed back to the relative cool of the apartment and planned the next day out.

On the 11th September we headed to Corrientes’ sister city across the river, Resistencia. Corrientes is smaller and more serious than Resistencia, even though it seems to try to keep up with all its murals. Resistencia is the real artists home however. Every year here they have a sculpture competition, and all the sculptures are exhibited all over town. They seem to be a huge source of pride, even with an exhibition space taking up one of the large parks in town.

Funnily enough, the first place we went to was not a sculptor’s studio or the exhibition gallery, but a museum. The Museo del Hombre Chaqueño is a great little museum grouped by the people’s who have inhabited the state of Chaco. It starts with an exhibit about the formation of the region however, with special focus on the War of the Triple Alliance, or the Paraguayan War. Fought between 1864 and 1870, the war saw Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil gang up on Paraguay after it’s President, Francisco Solano Lopez, commenced an aggressive policy of trying to gain control of the river basin region covering the Paraguay, Uruguay, Parana and other rivers. The war resulted in Paraguay losing 60-90% of its total population, and it was all over when Lopez was captured and killed. Argentina joined the war after remaining neutral (a position it has consistently held throughout history, even in WWI and WWII), when Paraguay took this neutrality to be aggressive and attacked the state of Corrientes.

The museum was extremely informative on this point, including the various viewpoints of why the war started (Paraguay’s land grab, the support of Brazil and Paraguay of various sides in Uruguay’s civil war, and a newer revisionist theory put forth by chest-thumping nationalists in Argentina and Paraguay that it was all the British fault). Our guide in the museum, Gustavo, was also extremely helpful, and gave us a lot of information and made the visit extremely worthwhile – a stark contrast to the museum in Resistencia’s sister city!

The sections dealing with the various groups of people living in the Chaco region told us of three distinct groups: criollos, immigrants and indigenous peoples. Criollos are a class of people of Spanish ancestry born in the Spanish colonies. Usually having some mixed ancestry with the indigenous population, the further a person got away from pure Spanish blood, the less legal rights they had: for example, the top jobs were all held for people born in Spain. Nowadays people here in Northern Argentina call themselves Criollo to denote they are locally born, or of Spanish ancestry; and also to differentiate themselves from the non-Spanish born European influenced portenos of Buenos Aires. Maps showed us that most Criollos moved into the area as economic migrants from other areas – the Guarani blooded people from the East, and the Quechan people from the Andes to the West.

We also saw similarities with Northern Brazil here in the Chaco region – many poor European immigrants had come to make a home here. The poorer they were, the further away from civilization they had to settle. The middle of the Chaco region is an arid, thorny dustbowl in which the Eastern Europeans had to settle between 1920 and 1950.

My favorite map was the one showing the current position of the leftover indigenous people’s of Northern Argentina. Where we were, in Resistencia, the Toba, or Qom people were still going relatively strong (much better than elsewhere where they were all wiped out completely).

A small meteorite was also on display here, from the region in the Argentine Chaco bordering Chaco state and Santiago del Estero state. This group of meteors are called Campo del Cielo (Field of the Sky) which is what the local Moqolt Indians referred to it as, even though it had fallen to Earth around 4000 to 5000 years ago. In 1576 the Spanish led an expedition to the area to see if they could recover the iron ore, and to see if it was part of a larger vein of iron in the ground. Believing it to be volcanic, and not from space, they documented the find and left it where it was. Their story was followed up by modern expeditions to find the meteorite for scientific interest, but it has never been found again – some believe that the Moqolt reburied their religious treasure, but it is more likely that soil erosion has hidden the largest piece. Much of the meteor has been recovered from the 60km square area, and some even was sent to London’s Natural History Museum which promptly exhibited it as the first large meteor to be displayed to the pubic in 1826. The biggest unbroken meteor in the world is in Namibia, Africa, but the second biggest fell at Campo del Cielo, and is called El Chaco. No-one knows for sure, but the meteor that was reburied could be a lot bigger than either of those! The combined weight of over 100 tons of the Argentine meteor makes it the heaviest meteorite recovered on Earth.

There were other indigenous artifacts on display in this section of the museum, and our favorite was a little single string violin made of wood, twine and an armadillo shell for the body of the instrument. There was also a giant cross-section from a large tree with a painting on it, that depicted the criolos working a loggers in the forest. Logging seems to have been the trade of choice for the population back in the 19th Century, with workers getting paid in silver or gold tokens that could be exchanged for the goods written on the tokens, for example 2 kilos of meat. This industry drove the building of the longest railroad of the time.

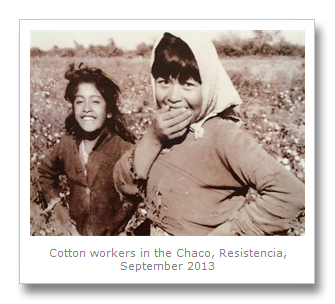

We also learnt that the ‘white gold’ of the Chaco region, cotton, was one of the most defining products and was responsible for bringing many of the immigrants to the region from Europe before WWI. In fact, by 1934 nearly 15% off the people in the Chaco were foreigners. Working in the cotton fields brought many of the three different peoples grouped by the museum (indigenous, criollo and immigrants) together and aided in the integration of the state. Another cool map showed the different cities in the Chaco state and when they were founded. Resistencia was founded in 1878.

Next to an exhibit on Gaucho Gil which we wrote about in our Buenos Aires post, was one about San La Muerte, which is pretty much the same as the Grim Reaper, or death. This non-Catholic saint is preyed to in this area, much like Gaucho Gil, to help with small favors, or cursing someone. This sort of superstitious nonsense is very popular all across this region, and the figure of death as an idol or saint actually did not come here from Europe but from Mexico, where they even celebrate the Day of the Dead festival.

One last thing we learnt whilst in this museum was where the name Argentina actually comes from: the Latin argentum, which means silver. There was a huge belief in large mountains of silver in the region by the Spanish, hence the name, although no silver was found in La Plata Basin. There were many objects that were made from silver exhibited in the museum, however, mostly to do with Gaucho culture, but also plates and cutlery too.

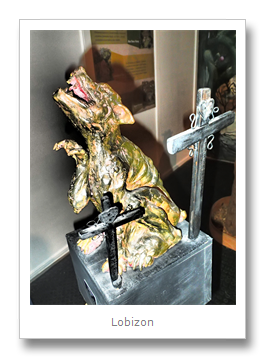

The last room, upstairs, was surely the best. La sala de Mitologia Guaranitica (The room of Gaurani Mythology) contained 11 small sculptures (by Ricardo Jara) of indigenous creatures on plinths surrounded by a backdrop of Chaco landscape painted on the wall. In fact, the mural (which covered both back walls) actually represented the Chaco countryside from East to West.

Our guide put an audiotape on, in English, and we learnt that before the Europeans came, certain creatures filled Guarani culture much like the pantheon of Greek gods filled Mount Olympus. Each fulfilled a purpose, had a backstory and all looked the part. Some were even related. They acted like protectors of the forest, of the environment, working against people who were over zealous when logging or fishing, even BEFORE the Europeans came. Like most gods they were fiercely jealous and mischievous – sometimes homicidally so. These creatures are still very much part of the rich Guarani heritage now, and are quite popular, even in modern times, after the wave of Christianity gripped the indigenous culture.

Kurupi is the oldest of these gods, with white ears, and blue-green eyes, he administers punishment on people who carry out excessive fishing, or logging. Punishment is normally a madness followed shortly by death. This god’s name changes dependent on the region you are in in South America, but it is agreed that Kurupi can appear as both man and woman, and either form has huge sexual organs! Kurupi is said to protect both women and lovers.

Kurupi’s son, Yashi-Yetere, (whose name means ‘little piece of moon’) is a red-haired child, often bearing a staff or stick that gives him his power. He is an evil god, and general nasty piece of work, as he spends his time stealing souls, leading children into the wilderness to make them lost, and causing epilepsy.

Wandering around during siesta or at night, Pombero’s big belly and straw hat are causes for concern as he makes people steal things; mostly animals or food that he likes (sugarcane, honey and eggs). In fact if you give the Pombero these food items, he might reward you with many riches. He also can appear as a good looking male, or cute animal, to lure married women away from their husbands. The sound of his bells have been known to make loggers go mad.

Pata de Lana’s resume is the least impressive; an ugly little dwarf figure, he is blamed for sexual abuse against women. No doubt a ridiculous alternative explanation for the very real acts of violence perpetrated by men who either used this myth as an excuse, or it was perpetuated by a family who did not want the truth to be learnt, thus protecting their social standing.

Aba Talon Yobay is the strangest, and perhaps most disturbing looking of all the creatures. He wears a huge straw hat that covers his whole head and body, all except his penis sticking out! He has two heels on each feet, so you cannot tell whether he is coming or going.

The custodian of nature, and my favorite of all the Guarani gods, is El Kuarajhi Yara. He is a big red bird in his natural form, and when flying, his wings leave a trail of rainbows behind. When seen by women, he can turn into a supernatural man who will seduce them instantly.

Caa Pora is another, lesser protector of the woods. Just like an Ent from Lord Of The Rings, he is essentially a living tree-man. He protects the forest by making the loggers confused and getting them lost in the wood.

One god who appears only on the 1st October is called Karai Octubre. This little old fellow punishes laziness with his whip. He is a teacher of accounting and sharing, and is a famous misery guts. Guarani people give a festival on this day when they share food with neighbors and shake sticks to dispel Karai’s depression, and stop him from doing anything too evil.

The famous werewolf myth is also alive and well in Guarani culture. Lobizon is a cursed half-man, half-wolf, who appears on full moons in lonely places. He becomes a big black dog or wolf, and can only be killed by a bullet blessed in a church (this is a Guarani-Christianity variation on an earlier pre-European kill method). In fact, all of these gods, although still popular, are now not as important to Guarani culture as they once were, and many elements of Christianity have blended into the indigenous way of life.

The Museo del Hombre Chaqueño was the best museum we had visited in Argentina so far, and is definitely recommended. We headed out from there, back into the scorching heat, to make our way 5 or 6 blocks down to El Fogón de los Arrieros, which is a kind of artist’s commune, housing sculptures, writers, poets and painters who work at the building. There was a closed (cerado) sign on the door, but as we had learnt to ignore this, we knocked on the door anyway, and we were greeted by a lady who ushered us inside. The artists were all sitting around having a meeting (we later found out it was a talk by the lady we had met in Corrientes’ Museo de Bellas Artes.

Inside, we paid the few dollars entrance fee, and got to walk around the ground an first floors of the workspace/gallery. Some artworks were strange and interesting, but all were totally unique reflecting the various mediums used by the artists. Even the toilet door was painted, and the garden had some cool statues and sculptures in it. Francesca and I agreed that this would be a great place to hold a party.

It does not take long to walk around El Fogon, but it is worth a visit. We made our way to the next museum on our list, and came across the plaza 25 de mayo. Filled with the regionally famous Resistencia sculptures, not to mention a whole host of amazing trees from the Chaco, it makes a nice diversion if you can find shade on a hot day. We found the tourist information office, where we encountered an enthusiastic Swiss guy who had emigrated to here for work. He was an accountant, but now helps out in the turismo sector of Chaco. Weird. We got our maps and left.

We decided to visit the Museo de Memoria in Resistencia, as it had been one of the famous illegal detention centers in Argentina during the dictatorship. It was much more informative and emotive than the one we visited in Rosario.

Filled with timelines, photos, maps and even excavations from underneath a false floor that the dictatorship installed, this museum is an interesting, if not a little creepy place to visit. 140 people disappeared in Chaco state, most of them men, and most of them in their 20’s. Survivors told of how they were bought to this house, taken over by the police in 1976, and questioned, tortured, and subjected to mock executions. They heard others being executed for real. All of this was never officially recognized by successive democratically elected governments, until the excavations, in 2008. These found hidden guns, cattle prods, bloody walls, and electrified walls and doors in the detention cells –the hidden layout exactly as described by survivors. A disturbing memorial to the horrific events in Argentina’s history.

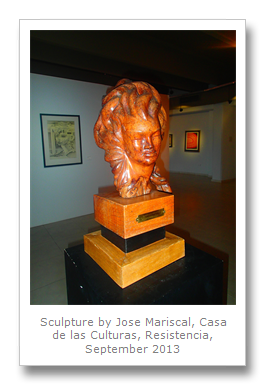

We left the museum and went a few doors down to Resistencia’s casa de las culturas, where we decided to have some lunch. After we finished our food we headed inside the building, which had several floors but not much going on. In the first room we found something in (there were many empty rooms), there was a modern art installation which I thought was rubbish. Leo Almada had written a nauseatingly saccharin introduction about himself and his art – some photos which looked like the crap photos we delete from our camera – was hung up in the room over some wooden crates. Unfortunately this sort of ‘art’ is now taken seriously the world over, and is passed off as interesting when in reality it is just lazy, useless rubbish. It is still worth the public money for the moment when a real talent does emerge, and it is no wonder this sort of shit ends up in a half-empty cultural center that no-one visits.

We saw some decent art on another floor, and as you can see from the picture, Francesca got to conduct an orchestra, but my favorite part of the cultural center was the glass painting of some workmen carrying wheelbarrows full of letters which had spilled over the floor. These letters were picked up by ants pained on the floor even on the outside of the building and they carried them to a book which was also painted on the floor. The cover had a hopscotch layout on it that kids could play on.

Along with the map of the town, we also had a map from the tourist information center in the 25th May plaza that showed the sculpture walk and where all the sculptures were. They were not labeled on the map though, which was annoying. The 30C+ degree heat really made seeing the whole sculpture walk impossible, so we chose a small section near the pedestrianized zone of the city and walked around that. The sculptures we did see were OK, but funnily enough they all reminded us of people going to the toilet! One sculpture did stand out though, as it matched one we had seen outside the artist’s studio at El Fogon. The statue was called ‘Fernando’ and it was of a very popular street dog that lived in Resistencia in the 50’s and 60’s. The dog used to be ‘owned’ by various artists and musicians, and often attended music events. It’s grave is outside El Fogon.

After escaping the sun in an A/C supermarket, and in the shade, we jumped on the bus back to Corrientes. It only takes an hour on the bus via the General Belgrano Bridge over the Rio Parana, but we found we had to stand the whole journey. It is pretty cheap, but quite uncomfortable during a heat wave.

The night we got back, we tried the Chamamé our new friend in the art museum had told us about; a pace called La Cocina, or the kitchen. We made it there, all dressed up, but no luck. They only do the folklore dancing on Fridays and Saturdays! We decided to once again skip it until we returned from Paraguay.

The next day we said our farewells to Jeronimo, and jumped in a taxi to the bus station. We bought tickets that would take us back through Resistencia on the other side of the river, and then up to Formosa, the capital of Formosa province – the last stop before Paraguay. We hadn’t got to see Francesca’s Chamamé, or my National Park, but in Formosa we hoped we would be able to see Parque Nacional Rio Pilcomayo. Maybe we would even see some endangered mammals?

No comments:

Post a Comment