We traveled to one of the world’s highest cities, Potosi, on the 3rd May. I was a little apprehensive about the journey because of the high altitude, but the super altitude (sorochi) pills I was taking still seemed to be doing the trick. As usual the mountain scenery was a joy to behold, very beautiful greens, reds and even yellows against a deep blue sky. Potosi itself was just as dumpy and broken down as every other Bolivian town we had seen, with houses that are unfinished, trash everywhere, including in the rivers which run as open sewers through the shanty-town neighborhoods, and dogs, pigs and people all contributing to the horrid and busy third world feel of the place.

Bus stations in Bolivia are all located outside the center of town, when there is a bus station in the first place! Potosi was an economic center and so did have one – in some other cities you are just dropped off outside the bus companies office, and have to find your own way to the center. We just normally ask for the main plaza and look for a hostel or hotel there, and Potosi was no exception.

A taxi took us to the main plaza, and we tried a couple of hostels, before settling on one which was cheap and cheerful. We handed some laundry in (an all too common occurrence) and then headed down to a tour agency which Francesca had been contacting. Big Deal tours rightfully has some excellent online reviews and a great reputation, and is run by some ex-miners who worked for many years in the Potosi silver mines. We arranged two tours with them to start the next day, and headed back to our hostel with some food. At such a high altitude, we were pretty cold that night – it must have been below freezing!

The next day, very early, we headed back down the few blocks to Big Deal Tour Agency. We were set, with several other tourists, to head off to a nearby mountain village called Santiago de Macha, or Macha for short in the early dark hours of the morning. It was a 5 hour drive to Macha from Potosi, mostly on a paved road, and with Big Deal’s good driver (a rarity in Bolivia), it was a pleasant drive. The region’s sole economic activity is subsistence agriculture, consisting of growing potatoes, corn, maize and other vegetables. We stopped off at a local eatery where we sampled some of these delicious foods in a healthy soup full of nutrients and vitamins, called lagua. This soup was creamy, with turnip, potato, some meat, and some other vegetables. It was delicious and warming.

We continued on to Macha, which is the site of a traditional Aymaran festival once every year called Tinku. Tinku is the Aymaran word for ‘physical attack’, and we had been warned about this explosive festival before we arrived. Amongst the colorful Aymaran traditional dress and group dancing are groups of men, and sometimes even women, getting blind drunk and fighting each other!

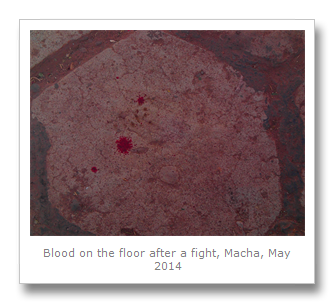

The tradition grew out of the belief of Pachamama, or Mother Earth, and the blood spilled from the fighting is considered an offering in the hope of a fruitful harvest. People from one village, will all travel together to Macha from villages from all across the region. They all bring food and drink (the ubiquitous 96% alcohol found all over Bolivia) and also the communities big decorated cross that they parade around, as Catholicism mixed with the Aymara traditions when the Spanish arrived. The Tinku itself lasts a few days, with the worst of the fighting on the last day – the day we were there!

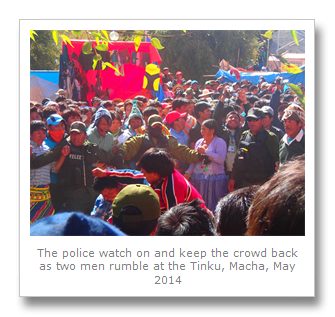

Within the first few minutes of us approaching the ‘celebrations’ outside the church on the plaza, the crowd surged towards us, scattering away from the police using tear gas sprays to separate a particularly vicious fight. We had heard fighters sometimes carry rocks to increase the force of their blows, even resorting to throwing them at each other sometimes. Our guide even told us that over the decades, many people had died at the Tinku festivals from their wounds, which is considered a particularly good offering for Pachamama! Life is really cheap in Bolivia!

The crowd rushed past us, knocking Francesca and I into a stall of Bolivian clothing. I covered Francesca protecting her from the surge, pushing people away from her, so she could not be crushed. When the madness had died down, we heard someone squealing in Spanish. We did not know where it came from at first, until we looked down and saw an ancient Bolivian woman complete with bowler hat crushed underneath us! We helped her up, apologizing, and she merely cackled, and disappeared off into the crowd. That is when we were first tear-gassed.

The tear-gas rolled over the square on the gentle breeze, shot from a police spray-gun, and immediately burnt our eyes and lungs. It took us some minutes to breathe and see again, and we were coughing and spitting. Blech!

A good question to ask at this point, is why on earth did we go there? It was certainly an interesting experience, and it was made much better because we found a couple of safe spots to watch from. One was from outside the police station next to the church, where we could see all of the action, and the other, later, was on top of a hostel roof, away from any violence, but overlooking all the action too.

Music was a constant during the Tinku, played by the colorfully dressed men holding drums, charangos (guitars made from armadillo shells) and panpipes. They marched and jogged together around the square playing the music, stopping every now and then to dance. The participants would eat every now and then, and then, when ready to go and fight, they would drink copious amounts of alcohol and go and fight the other communities. Bad blood between the communities is said to be expressed during these fights, and when there is a death, revenge is often the motive of more fighting, and more deaths.

We did not hear of any one who died at the Tinku we went to. Although we saw many men who were bloodied and drunk, and we saw many fights, including people being kicked whilst on the floor, the violence did not particularly feel threatening to us, and it did not feel real sometimes. I guess the ridiculousness of the situation was not really comprehended by our minds at the time – some of the violence was vicious and aggressive, so much so that a few of the other female tourists in our group freaked out a little bit. I guess they came unprepared for seeing such strange humanity.

A few people were harassed when we were there – including a foreign photographer who was not wearing the requisite credentials (you had to buy a license to take photos – but we got away with this by being discrete).

Most of the time the fights were structured, with only two guys fighting at a time; and the woman in each community did a good job of calming the drunken machismos down.

Although a tradition, the Tinku is a ridiculous practice, but it seems that it s quieting down a bit as time goes on. Some of the older guys were definitely taking the fighting and bad blood very seriously, but a lot of the younger guys were wearing jeans under their customary dress. In 2014 there is no place for a festival where people are killed in this way, and even though the people involved are among the poorest and least educated in South America, the authorities should be ashamed that they let this barbaric nonsense continue.

We were taken to a little restaurant by our guides halfway through the day were we all sat down together and ate a typical local lunch of meat and potatoes. Delicious! After this, we went to a little dark and dank room where lots of drunk Bolivian men danced around drinking chicha, a rough local brew made from maize. The men were pretty dirty and gross, stinking of body odor, drink and coca leaves. They were also pretty creepy, trying to grope and grab all the girls in our group. I got pretty bored with this so Francesca and I left and walked around the town on our own.

Many market stalls selling everything from clothing to sugar cane were spread all around the plaza. Drunk guys were everywhere, and we stood out pretty well, so spent much of the time keeping a low profile. We saw some tourists had climbed to the top of the crumbling bell tower on the church to get a view of the fighting, but it was not until the end of the day, when we were safe on top of the hostel roof that we saw a few more scrapes between belligerents.

The crosses carried by the communities were taken to the church to be blessed. Much chicha was thrown at the church and on to the floor in deference to Pachamama, and it was a sight to see the colorful crosses being paraded around by dancing groups. Some men carried whips to keep their group moving, and also inline. It seemed that the police had had enough of the fighting though, and would not allow anymore. We stayed on the plaza until we were meant to leave, because the police were only present there, and we had also heard attacks happen away from the police.

When it came time to leave, it was a bit of a relief. We had a long drive home, and I think everyone had had enough of the repetitive music and dancing, and enough of the drunken violence. We took a day the next day to relax and get over the festival, and then, the day after we went on our second tour with Big Deal Tours.

On the 7th May we headed back over to the agency and were taken with a different group of people to the famous Potosi silver mine. Potosi was founded in 1545 to be a mining center and grew so rich and important, it is now a UNESCO World Heritage center. The local mountain is called Cerro Rico, or rich mountain, after the incalculable silver that was stored there. 41,000 tons of silver was mined from it between 1556 and 1783, and miners are still pulling rich minerals, including much silver from it today. A working mine, it has long been hosting tourists from all over the world. Another dangerous activity, we had decided to again go with Big Deal Tours, as they had excellent reviews and ex-miners who would lead us through the labyrinthine passages and intricate etiquettes of the mining community.

The morning started at the miner’s market, where we could buy optional gifts for the miners. As most miners work long hours in cramped and pretty crappy conditions, we bought them some coca leaves to chew and some soft drinks. Some people even bought them dynamite!

Next we got kitted out with some pretty smelly overalls. Dirty and stinking of sweat, the overalls and even the miner’s helmet were pretty gross to wear, but we were going to be crawling through some pretty mucky and toxic environments anyway, so we just had to put up with it.

From here we walked up to the silver refinery, where we were given a tour around and shown how they separate the good stuff from the bad. A group of miners would work on their own part of the mine, where no other miner is allowed to work, and they would collect as much material as they could find, and then bring it to the refinery, where they would pay to get the silver extracted. The more silver there was, the more money they got, basically. The guide told us he sometimes used to make thousands of dollars a month, and sometime would get next to nothing.

The refining process itself was very simple, but we had to wear masks to protect against the chemicals used such as mercury. Basically, water helped separate the silver once the raw material had been crushed and heated down into a liquid, and it was then put into cooling tanks. These techniques are centuries old, and quite effective for the Potosi mine. It is a dirty process, but someone ha to do it.

Sometimes the miners would even get together and pay the refinery to rent the equipment and do the extraction themselves – this was a big gamble, as it was expensive. However, if you found lots of silver, you could strike it rich this way, and maybe even retire. Apparently one miner invested all his money this way, found nothing, and went broke. It was back to the mine for him, even though he had retired already on a previous fortune.

Back to the van and we started up Cerro Rico. The mountain is awash with different colors from the minerals that make it so rich. Our guides told us that the name Potosi is an indigenous word, meaning loud thunderous noise, possibly referring to an old legend that says a loud thunderous voice told the people not to mine the mountain, or maybe from the noise of the explosions heard from within the mine itself. Local oral tradition also states the name is an onomatopoeic word describing the sound a hammer makes when striking the ore.

Either way, we had arrived at the Potosi mine, where several miners were ending or starting their shifts. They have no boss to speak of, they just turn up whenever they want, and work. There are no enforced rules about how long they work for, and we would soon see what the conditions were like inside.

A short walk and then a lift took us far down into the depths of the mountain. Miners passed us pushing heavy trolleys that ran on tracks that were filled with ore. Wooden beams kept the rocks above us in place, and wet muddy silt was all over the floor. Lucky we were given boots! The light from our helmets showed us the way, as our guide led us further into the mine, stopping to question the miners about their day, age, hours and experience in Quechuan. Gifts for the miners were liberally distributed, and especially popular were the cool soft drinks, as many miners had been working for over 10 hours through the night.

The atmosphere in the mine was extremely dusty, and it was easy to see why many miners die at an early age with all sorts of health problems. Our guide even told us his uncle had gotten really sick with cancer after working for decades in the mine, and had to go live at a lower altitude so that he could breathe more easily. He did seem to be blaming this on an unhealthy lifestyle of smoking and alcohol though, which struck me as being in denial a little bit.

Indeed, the guide went out of his way to denounce the movie, ‘The Devil’s Miner’, which shows the gritty and unhealthy lifestyle of the Potosi miners. Nowadays, he said, miners live pretty good lives and are happy and proud to do the honest job under the mountain. Co-operatives had been set up where friends and family work side by side. Anyone can work there as long as they show dedication and seriousness – the job has many peaks and troughs where the miners either find a vein of silver, or do not. Questioning of method and technique is actively discouraged by the older and more experienced miners so that the younger miners who are learning the ropes do not get confused, and therefore injured in the dangerous environment.

We had to climb some difficult ladders – difficult because of the cloying and choking atmosphere and the high altitude we were at. We finally arrived, however, at some passages were we watched as one miner allowed us to take pictures of him hammering away at the rocks trying to create some holes for dynamite. In fact, there were several sticks already in place. Dynamiting is done only when no-one else is around. The miners have a mental picture of exactly where everyone is, including the other groups working around other passageways.

These approaches were very traditional, and the miners unions refused access to any large corporations so that the miners and their next generations always had the mine as an option. This seemed pretty backward to me, as many miners do suffer bad health or injuries in the Potosi mines. It is one thing respecting people’s traditions and cultures, but we found in Potosi a clinging to outdated values, in the mines and the Tinku festival, that only serve to harm the individuals in that society.

A less harmful tradition was the belief and reference in the devil-God Tio. Tio means uncle in Spanish, but down in the mine, he was the living embodiment of lewd behavior. We sat before the statue which exists in all Bolivian mines. It was a red devil, replete with horns and a huge erection! Covered in colored paper and surrounded with beer and wine bottles and gifts of cigarettes, it made for a very interesting shrine.

We sat around the strange statue, and the guide told us about some of the superstitions the miners have. One is that they often see long dead miners, especially those of friends or relatives, which they believe is Tio, walking around in the mine. Reports of people talking with other miners, their friends, for hours, only to find out later that that particular friend was not working that day! Ridiculous of course, but easy to understand when people can turn up whenever they want, and forget what day they were working, and miners were spending so many hours underground chewing so much coca.

Our guide wrapped things up and we all headed off to the exit. Without our guide, we could easily get lost amongst the myriad of passageways and different levels there were. We actually had walked through the entire mountain over around 3 or 4 hours, all the while handing out gifts of coca, drinks and dynamite! Our guide chewed coca the whole time, as did some of the more idiotic tourists who were trying their best to impress. Coca tastes disgusting and bitter though, so we certainly did not. The youngest miner we had seen had gone against the rules of over 18s only, as he had started working there when he was 12! It reminded me of the Victorian Britain I was taught about in school.

It was a beautiful day outside, and so we headed back past the working class suburbs serving the mine, gave our safety equipment back, and headed back to the hostel for a shower.

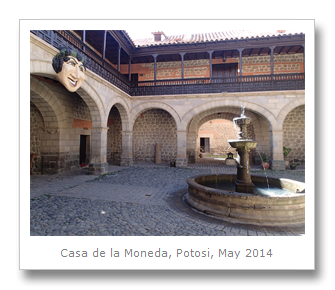

The next day, the 8th May, I headed over to a museum called the casa de la moneda, which was Bolivia’s original mint! As the silver was found in Potosi, it made perfect sense that the mint would be located there. Initially, a hammering technique was used, whereby a sheet of silver was placed between two molds, and a hammer struck the top mold. This would produce a coin. This techniques lasted for two hundred years until a screw press was introduced in 1767. The cost of the mint building was so expensive that apparently King Charles III of Spain said at the time that “the whole building must be made of silver”.

It was not all fun and riches though, as the mint was the destination of many African slaves, forced into making coins under terrible conditions. The smelting rooms would have been intolerably hot as the slaves would be forced to work for days on end.

We saw some rolling mills as we were guided around (English tours are only at certain times), which were used to flatten silver bars. Mules were used to pull the mill which had been sent to Potosi from Spain to help create better coins.

The building itself was a very pretty colonial building, and had a lovely collection of minerals too.

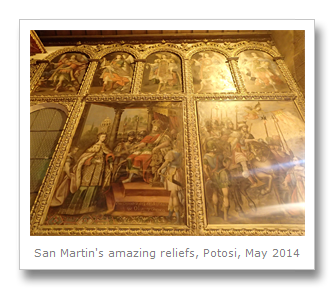

Potosi is not just known for its mine, but also for it’s churches. Of course, where there is money, the Catholic church is not far away! We visited numerous churches, many of which had very pretty facades, bell tower views, altars and designs. San Bernado had a striking boulder façade, a Jesuit bell tower now serves as an entrance to a tourist information office and San Martin had an amazing gold altar.

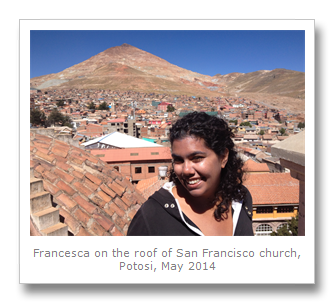

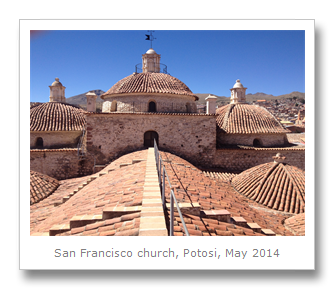

My favorite church to visit was the San Francisco Convent which was the first convent built in Bolivia in the 1540s. 300 indigenous workers built the church, cloisters and crypts. There were 24 reliefs painted around the inner courtyard, depicting the life of Francis of Assisi. Only 3 friars now live in the convent. We even saw an indigenous looking Jesus there, dating from 1550. The crypts had been where the rich families of Potosi had been buried over the centuries, until they were all moved to a local cemetery in the 18th Century.

Another interesting convent was the Santa Teresa Carmelite church, particularly the secret rooms were they used to flagellate themselves with barbed whips! The nuns lives must have been pretty brutal, as everything they did was watched by the sisters, and anything deemed impure was punished. Unfortunately, the staff at the church were really annoying and the guide was an irritating power-mad turnkey who did nothing to make the experience a good one.

Another small university museum was pretty interesting and eclectic, with everything from local modern art to dinosaur bones, archaeological findings to colonial furniture. This was only 4 small rooms though, so did not take much to get around.

Potosi was an awesome city to visit, and definitely a recommend as there are many things to do there. Just make sure you wrap up warm at night!

No comments:

Post a Comment