On the 11th March Francesca and I headed on the metro into Santiago town and went to the Patronata district, which is North of the Mapocho river. We had been let down by the guide of the just-for-tips Spicychile tour a few days before, and so I took their tour of this area, and made it my own (using Wikipedia and the governmental websites).

At each stop, I would use Google maps, and my pre-written speech about the area to conduct the tour. It went pretty well – we both were able to go at our own speed, and we had a lot fun! Here is the tour I gave – anyone who finds this can use, copy or edit it as they please:

Metro: Patronata

“Patronata is an underground metro station on the Line 2 of the Santiago Metro, in Santiago, Chile. The tunnel that connects the station with Puente Cal y Canto metro station passes under the Mapocho River. The station is named after the barrio where it is located, which is Barrio Patronata.”

Barrio Patronata

“Barrio Patronata (Patronata Neighborhood) is a traditional neighborhood in Santiago. It is bounded by Avenida Recoleta to the west, Bellavista Street to the south, Loreto Street to the east, and Dominica street to the north. Administratively, it is located in the Recoleta commune.

The neighborhood was turned into a commercial district with the arrival of Middle Eastern (Arab, Palestinian, Syrian, Lebanese) immigrants since late 19th century. In early 20th century there was a massive influx of Palestinian and Lebanese Christians fleeing the Ottoman Empire due to religious persecution, and later the economic situation and the outbreak of World War I. They were followed by Koreans, Chinese, Peruvians, and people of other cultures.

The neighborhood is known as a shopping area for affordable, trendy clothes. It is possible to find Arabic restaurants. It is also possible to find restaurants serving South Korean and Vietnamese cuisine. The neighborhood is also home to the historic church, Parroquia de Santa Filomena, and also to the Vega Central, or main marketplace for fresh fruits and vegetables. Which is where we are going now!”

La Vega Marketplace

“La Vega Central is also known as the Feria Mapocho (Mapocho market) almost at the north bank of the Mapocho River. Mapocho is Mapungundun for 'water that penetrates the land'. A wide variety of products are sold in the market's surrounds, principally fresh fruit and vegetables from the Chilean Central Valley. La Vega Central is also home to over 500 dairy, meat, goods and merchandise stores, and offers a variety of Chilean cuisine. Today, hundreds of thousands of people pass daily through La Vega’s 60,000 square meters of stalls. La Vega Central has now achieved iconic status in Chile’s capital. A long-time vendor at the market was quoted as saying, ‘Markets nowadays compete (for customers) by using marketing, but La Vega has never had to resort to this. It subsists on its own creation and that is its magic.’

From the colonial era, farmers gathered in La Chimba sector to sell their products. La Chimba was the section of Santiago located at the northern side of the river, which in Quechan means, literally, 'the other side'. With the construction of the Puente de Calicanto in 1772 to help minimize the area's isolation, a large number of vendors and merchants began to set up their stalls here. In the 19th Century, when the area was known as “La Vega del Mapocho” (the Mapocho market) the land was delimited and designated for product consumption, taking advantage of the channeling of the Mapocho River. New storage houses were also built to load and sell agricultural products. An initiative by Agustín Gómez García led to the construction of La Vega Central in 1895, with the installation of warehouses made of solid material inaugurated in 1916. La Chimba is now known as the districts of Recolleta and Independencia.”

Tirso de Molina Market (Fruit/Veg Market)

“The origins of this market were the trams. The tram terminals ended here, and so that bought street and illegal traders, which persisted from 1955 onwards when trams changed to buses. The market is now a market for fruit, vegetables and groceries, clothing stores of both national and international renown. Its name is in honor of the 17th Century Spanish Baroque playwright and poet, Tirso de Molina, which was the pseudonym of Fray Gabriel Téllez. This comes from a resurgence in his popularity at the time of the market's conception due to a republication of his books in Spanish.”

La Pérgola de las Flores (Flower Market)

“Architectural and conceptually, the Pergola Santa Maria and San Francisco, are a single large project: same height, modulation, concepts and materials, i.e. a building constructed with simplicity, yet designed for intensive use and as an architectural icon in a place steeped in symbolism and popular identity.

In the recent construction, the new market was conceived as a large deck that rests on a web of tall pillars, like artificial trees. The cover modules are 6 x 6 meters. Each module consists of a pyramidal structure with inverted translucent ceiling, with interior lighting.”

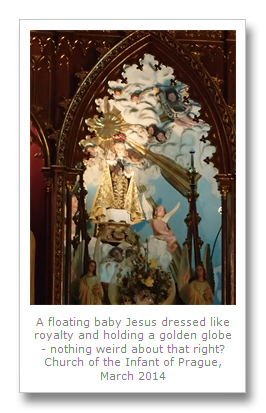

Iglesia del Niño de Praga (Church of the Infant of Prague)

“The Infant Jesus of Prague is a 16th-century Roman Catholic wax-coated wooden statue of the baby Jesus holding a globe crucifix, located in the Carmelite Church of Our Lady Victorious in Malá Strana, Prague, Czech Republic. Pious legends state that the statue once belonged to Saint Teresa of Avila and allegedly holds miraculous powers, especially among expectant mothers. No one really knows where this baby Jesus came fro, but there are a rash of them all over the world, with different names and superpowers. A photo of the Christ-child statue even appeared in the music video 'Beat It' by Michael Jackson, placed above his bed. The church was founded in March 29, 1900, and was the HQ of the Carmelite order whose focus apparently is contemplation and miracle dolls.”

Estacion Mapocho (Mapoche Train Station)

“Built at the beginning of the 20th century, the Estación Mapocho was for a long time the hub for all rail traffic serving northern Chile, Valparaiso and Argentina. Built to celebrate the centennial of Chilean independence, the building has an obvious sentimental value that adds to its imposing architecture. In recognition of all these attributes, the building was declared a national monument in 1976. It is located on the south bank of the Mapocho River and close to the Mercado Central de Santiago. Puente Cal y Canto metro station is beneath the square in front of the station.

The demand and quality of rail traffic to northern Chile had however been decreasing up until then, and would continue to do so up until 1987 when the building was decommissioned due to serious structural decay. Since demolition of a national monument is expressly forbidden, the building remained in disuse and awaiting repair until 1991 when the government green lit a remodeling of the station. The building was repaired and restored by the beginning of 1994. Since rail traffic was no longer operating to its former destinations, the station passed into a new life, but retaining its name.

The Estación Mapocho building now serves as a cultural center. The station is used primarily for art exhibits, musical performances, and conventions.”

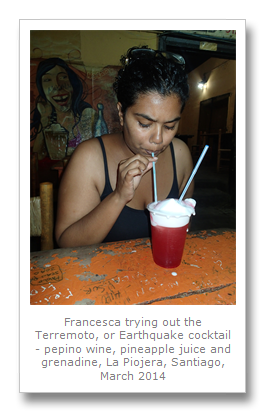

La Piojera Bar

“Located in street Aillavilú, which is Mapundungun for nine snakes, La Piojera is named after any bar that is remarkably dirty. Arturo Palma , who was President of Chile in 1922 asked to be bought to one, and christened the bar when he was shocked on his arrival. It became a tradition for other presidents to visit, including even President Allende. It was bought first in 1916 by the Pini family, and they still run it today. The terremoto or earthquake drink was named after the 1985 earthquake, but no-one really has the true story of who or when this happened as the recipe was a secret for awhile.”

Mercado Central

“The Mercado Central de Santiago is the central market of Santiago de Chile. It was opened in 1872 and Fermín Vivaceta was in charge of its construction. The market replaced the Plaza del Abasto, which was destroyed by a fire in 1864.The market is housed in a building whose main feature is a cast-iron roof and supporting structure, which was fabricated by Messrs. Laidlaw & Sons of Glasgow. Edward Woods and Charles Henry Driver (who helped build the Crystal Palace in London) also took part in the design of the structure.

The metal structure stands on a square base and features a vaulted ceiling. Its intricate roof design consists of a central pyramidal roof crowned by a domed tower, which is surrounded by 8 smaller roofs with a two-tier design. The structure is enclosed by a masonry building.”

Finishing the tour at the central marketplace left us pretty central, and also able to get some food (we recommend going outside of the market away from the annoying touts to the cheaper local places around the corner).

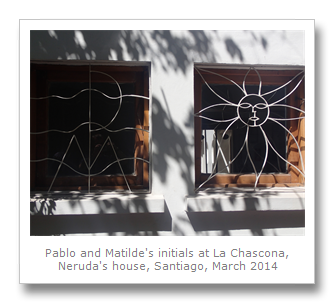

We jumped on a metro to the Bellavista area, and walked around for awhile, admiring the bohemian bars – the part I liked the best was the Bellavista Patio – an enclave of decent eateries and little boutique shops. It was clean and nice to window shop for about half an hour or so. We made our way to Chilean poet Pablo Naruda’s old house, called La Chascona, which was located on the side of Cerro San Cristobal, a hill in central Santiago that overlooks the city.

The house is very quirky, likewise the ex-owner – Naruda’s character was explored through the audio guide that visitor’s get on entry. He seemed to have a fascination with the sea, which was reflected in nautical themes throughout the house. He even got people to call him ‘El Capitan’. This kind of pretentiousness, although usual for famous artists, extended to the layout of his house – for example, the secret doorway through which he would enter, like royalty, to the surprise of his seated dinner guests. It was in this way he would hold court and entertain his friends and his lover Matilde. In fact, Naruda cheated on his wife with Matilde for years before he decided to come clean and get divorced – Matilde would be his third wife whom he named the house for (because of her messy red hair). There is a painting in the house by Mexican artist Diego Rivera (lover of Frida Kahlo) depicting Matilde with two faces – Rivera painted it at a time when he knew about the affair but it was not yet public. One shows the public image of Matilde, and the other, Naruda’s secret lover. Naruda’s profile can be seen hidden in her hair. The painting was given to the couple as a gift - it is incredible that a group of people can behave so badly – Naruda’s wife must have been devastated when she found all of this out, thinking they were all playing a big joke on her. She may have expected this though, as he cheated with her on his first wife.

It seems to me that the whole collection of these Communist artists, like Naruda and Rivera, where complete hypocrites whose terrible behavior belied their so-called convictions. They were bourgeois, with Neruda himself owning several houses – La Chascona was just the one he built to hide his lover. The artifacts inside the home were all pretty lovely, but also expensive – and it was not until Stalin’s full crimes came to light that Naruda stopped praising the dictator.

Naruda was, however, a prolific and celebrated poet and diplomat for Chile. He criticized the US throughout his life, siding instead with Communist governments worldwide. When his beloved Chile was taken over by the dictator Pinochet, Naruda’s health massively declined, and he died twelve days later (he had cancer). La Chascona was looted and purposefully flooded the days and weeks after the military took over – many books were burnt. Matilde refused to leave, however, and she held Naruda’s funeral and wake at the house, even with it’s broken windows.

When at La Chascona, Naruda had liked to sit reading, and entertained guests whilst taking in the view of the Andes mountains, which, when the smog lifts, can be seen clearly from Santiago. It is not a huge house, and not all of it is open to the public, but the objects and art on display are pretty interesting, including Naruda’s Nobel Prize for Literature.

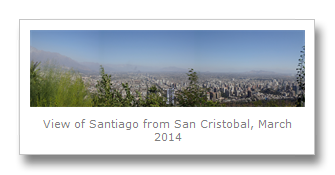

We walked back into the sunshine, and walked a few hundred meters around the large hill of San Cristobal to the Funicular which is a basically a tram pulled up the hill by a cable. We took it up, and the views were pretty awesome. Again, we were thwarted by the smog a little, but it was nice being up with a view over Santiago. There is a large statue of the Virgin Mary up there, too. Since 1561 when a wooden cross 10 meters high was dragged up there, the hill has been a focal point for Christian pilgrims – even the pope made it up there to bless the city in his ‘peace and reconciliation’ visit of 1987. Even the Mapuche call the Tupahue, which means ‘place of the gods’. The name change was for the San Cristobal family, who began quarrying the limestone on the hill for almost two hundred years. The stone was used to build some of the most famous and recognizable buildings in the center, but the quarry was closed when angry residents around the hill started getting bits of rock tumbling down on top of them when dynamite was exploded.

Also on the hill is the Santiago Cable Car and the zoo, but we missed out on the cable car, and the zoo is supposed to be hideous – I don’t think I could ever go to another zoo after seeing macaws flying free in the Pantanal and Amazon.

The next day we got up early (for us), and went into town again for a history walking tour, this time with Turismo Reportaje. A new company started by mother and son, they specialize in doing tours with interesting angles that teach about the Chilean character. However, we got the wrong date, so we resolved to go back the next day. We did get to see Francesca’s old workplace though, Banco de Chile.

We ended up at the main square of the city – the Plaza de Armas. They are working on making it safer and extending the shaded parts of the plaza, so most of it was boarded off, so we started our way towards the cathedral, but that was completely blocked by police. Turns out the new president was at a traditional service in the cathedral, and so we waited and had some lunch (avocado on toast – avocado is one of the most popular food items in Chile). The pres. came out, and the newsmen all started snapping away. The police did a good job keeping us all away though, so we only got to see the scrum around her. We saw more on the TV in the restaurant we had been in. It was nice to see the cavalry all marching along behind the car though, even if it was a bit ostentatious for just one person.

We went around to the other side of the square and dipped into the Postal Museum which I though would be really boring, but it turned out it was OK. They had a collection of really old stamps, including a flawless Penny Black, the first stamp ever produced (in England). They also had stamps sent to them from all the other countries in the world who belong to the Universal Postal Union. This Union means they all get a copy of first edition stamps sent to them by the other participating countries. I also saw a real Post Office Box for the first time – a whole bank of them which people were using, near some safety deposit boxes. The museum used to be Pedro de Valdivia’s house, the founder of Santiago; and was also used as the President’s residence until 1846.

Around the corner we found another museum – Santiago is built for people who like museums! We bought our tickets and went into the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino (Chilean museum of pre-Columbian art). This museum had by far the best collection of ancient artifacts we have ever seen – from all over Latin America. The explanations were good, and in English, and the whole thing was done spectacularly well.

The first room we discovered was the ‘Before Chile’ room – the ancient indigenous artifacts discovered in Chile itself. The Chinchorro mummies were the oldest mummified human bodies ever found – two thousand years before the Egyptians started doing it. One mummy was even dated back to 7020BC, a full four thousand years before the oldest Egyptian mummy found. They removed the internal organs and replaced them with leather, feathers and vegetable fibers. They covered the bodies with mud, and even gave them a wig. Not much else is known about this culture, such as why they started embalming their dead – testing only showed that their diet was mostly seafood – and they also made clay masks that they would sometimes use to cover the dead’s facial features.

Some of the oldest objects in South America are stone artifacts from Northern Chile’s coast of the Atacama desert region. The museum suggests they have a ritual or ceremonial function, but they looked like children’s toys or shapes to me. In fact, as much as 6000 years ago, the people’s of the North were expert stoneworkers, creating extremely sharp silica knives. These people’s ancestors were hunter/gatherers who settled in the region around 12,000 years ago.

Numerous examples of woven bags were on display, found mostly in burial chambers and tombs from many different cultures across the region, as well as the popular unku or tunic. The oldest ones were found near the Northern city of Arica from 500BC, just South of Peru, and it is thought that it fashionably spread across the desert region, along with various woven hats, until being appropriated by the Incans 2000 years later. The loom was invented in this area around 1000BC and so many items of clothing were already being made from the numerous camelids’ fur, such as llama and alpaca. Many of the techniques used back then are still in use today, especially by the Aymara people, who, although conquered by the Incans, remained fairly autonomous. Around 2 million Aymara still live in Chile, Bolivia and Peru, and their culture has enjoyed an expertise in metalworking for thousands of years. The chiefs, when authorized by the King of Spain, carried a staff of power, called santurei. These were made of palm wood and decorated with silver rings – and are still used today (we hope to get to see one!), often kept in churches as the people have been converted to Catholicism.

The Incans seemed to be the most advanced, being the most recent empire in Northern Chile, Peru, Northern Argentina and Bolivia. On display were some of the accountancy tools used – a kind of abacus but made of strings tied together. These quipus on display could hold up to 15,024 bytes of data, including zeros, represented by the knots tied into it.

Smoking apparatus were also on display, from when native people would smoke psychoactive ingredients and get high. Spoons, pipes and canes were used to snuff as much gear that the shamans could get their hands on.

Ceramics from the Arica and San Pedro cultures (both named for the nearest city to where they were found as we know hardly anything about them) were also displayed. The San Pedro natives made monochrome items, whereas the Arica tribes, right next door, made multi-colored objects. These styles of art were both copied and adopted from the Tiwanaku culture which ruled over what would become the central Incan empire of Northern Chile, and Southern Bolivia and Peru between 500AD to 1100AD.

The cultures that came from the Chile like the Diaguitas who came to be around 1000 years ago, before being assimilated into the Incan empire, became some of the first to begin using human figures on their art. The paintings on their ceramics show us how people may have dressed – but they also have a lot of anthropomorphic figures, especially large cats like the powerful jaguar. The Mapuche believed that the ruler of the seas and the ruler of the land were engaged in an ongoing struggle much like good and evil – presumably because of the constant tsunamis in the region – and used an alligator and a snake to represent these forces.

Some of the clothing was kept in such pristine condition the colors from a thousand years ago could be seen clearly. It is a wonder how they lasted so long without fading!

Back on the ground floor, we discovered a little interactive part of the museum, in which we had to fill out a questionnaire which went on to reveal which tribe we would most likely fit into – questions such as whether we liked hot or cold weather, etc.. Francesca went first, and she was an Aonikenk indian – a type of Tehuelche native who even the Mapuche warrior called the ‘fierce people’! So watch out! I got the Diaguita tribe – they were famous for their black, red and white pottery…

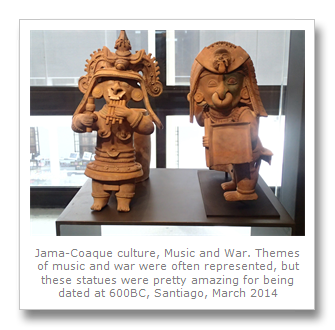

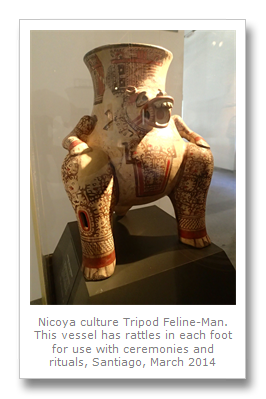

The rest of the museum was dedicated to art from pre-Columbian times from all over the rest of Latin America. The quality and condition of the pieces were amazing, and some of my favorite pieces were from these cultures – especially Mayan, Nicoya and Nayarit cultures.

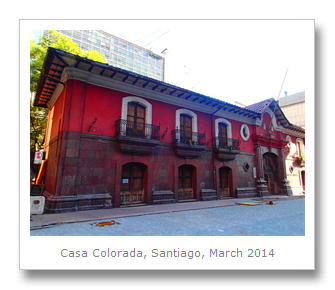

After the pre-Columbian art museum, we headed over to a colonial house, called casa colorada, or red house. This was built in 1769, but was under restoration when we were there – there is a museum inside, but it was also closed. Looked nice though!

We headed back home as it was getting pretty late – and we had planned on going to the walking tour we missed the previous day. On 13th March, we again went to meet up with the walking tour from Turismo Reportaje. This walking tour was centered around the life of Salvador Allende, the controversial figure who was president when Pinochet took over during the coup of 1973. The tour started at a metro stop, and we were the only ones on it – but it turned out it was pretty good, so I hope the company gets more people interested!

We started off where Allende went to University and studied to be a doctor at the Universidad de Chile. This was the area where Francesca saw the 2011 student protests and subsequent riots! We also passed the La Moneda Palace, where we would go for a tour some days later. This is the building which was bombed by the military in 1973 when the dictatorship took over. Allende was in the building and refused to hand over power. He made a few radio addresses to the people and then shot himself twice in the head (at least that was the official version – he was probably murdered after a firefight). His body was carried out the door used by Presidents when leaving office, and he was laid to rest in Valparaiso. It was only after democracy was restored that Allende’s body was moved to a more prominent spot in the general cemetery.

We learnt how Allende was a confident and honorable president, but a tragic figure who could not get the economy right. It was this that was his downfall, and the main reason behind the military’s decision to strike. Pinochet and Allende were in fact friends before the crisis, even with Allende’s Marxist beliefs. He ran for President four times, and because he was only elected with a minority the fourth and only time he won, the military and his opponents had the excuse they needed for a coup. Obviously Chile was not ready for this brand of socialism.

Now Allende and Pinochet both represent the left and right wings of the politics of Chile, respectively, and the country is still completely divided as to who they support. Even after the horrors of the dictatorship came to light, people even today support Pinochet and his tactics, as a necessary evil that bought the country back from near destruction by Communism.

We also saw the ex-congress building, which was used as the seat of legislative power until Pinochet expelled the politicians to Valparaiso, which is where Congress is still held today. Allende was considered a hard-working man by his fellow congressmen, and we were even told a story about how he challenged a congressman to a duel over a lady they were both seeing (both men were having affairs). The duel took place, shots were fired, but neither men were injured. Allende almost lost his job over that debacle, and it turned out the men were both seeing different women anyway! Idiots.

We checked out the cathedral again after the tour was over, and then made our way to the National History Museum. This museum started off pretty tediously but progressively got more interesting as we learnt about Chile through the ages, particularly about Santiago. Being the seat of all the power, Santiago pretty much is Chile.

We learnt about the channeling of the Mapocho river and the boom and bust periods of the cities past. The 1920’s and 30’s were especially good times with the elite getting rich from nitrate mining amongst other things. We also learnt about US interference with Chile’s politics, including incentives given by JFK to make agricultural reforms to wean the people of Latin America away from Communist leanings. This paved the way to partnerships with the other Southern Cone countries, which would eventually end in bloodshed when Operation Condor took place (to kill anyone with leftist tendencies).

The museum was littered with contemporary art which made the whole experience more confusing, and, for me, definitely detracted from learning anything – but I did enjoy going up the clock tower at the end. They do little guided visits up there when they have enough people, and the views of the plaza and the church were really great! If it were not for the ever-present smog, the view of the Andes would probably be awesome too.

It had been a long day, we had learnt a lot about Chile’s political past, and in the next few days we would learn more about it’s dictatorship.

No comments:

Post a Comment