Saturday the 22nd February we left Temuco and headed to the coastal city of Concepcion. We were staying with Eric, a first-time couchsurfer host who lived just to the South of el Rio Bio-Bio (the Bio Bio river). The river marks the Northernmost point of the lands claimed by the indigenous Mapuche people, and is firmly in the danger zone for Chilean earthquakes and their subsequent tsunamis. A 2010 8.8 earthquake/tsunami badly affected this region destroying huge parts of the coast and killing hundreds of people.

Transport in Southern Chile leaves a lot to be desired (some of the worst in South America), and we soon encountered more than our fair share of problems whilst in Concepcion. Our first problem was arriving at the wrong bus station – no-one told us that there was more than one, or that Terminal de Buses Collao was the main station. At numerous times whilst travelling in Patagonia and Southern Chile in particular, we wished we had rented a car. It would have saved so much time and therefore accommodation costs, and made us more independent. It would take some planning too, though, as there are only so many places that allow you to hire a car and drop it off in a different city.

We finally met up with Eric, and we all jumped in one of the mad micros, which are the small buses that crazily buzz their way all over the city. Most of the drivers are not fit to hold these jobs, and we did see one bus that was destroyed after a vicious-looking crash in Eric’s neighborhood. Eric lived in a town called San Pedro de la Paz which is in the South of Greater Concepcion. Concepcion sits on the North bank of the Bio Bio river, it is surrounded by numerous satellite towns like San Pedro, and is now the third largest conurbation in Chile.

Confusing multiple bus stations seemed to be the norm in this part of Chile – they have different terminals for different companies, different terminals for inter region and national travel, and different terminals for no logical reason whatsoever! Eric’s apartment was nice though. He had decided on moving down to Concepcion from the North, and had bought into a mortgage for more independence. It seemed to me to be quite a high price to pay (25 years repayment at 150% of the asking price), but this followed the trend we had noticed in South America of high borrowing amid a credit-driven bubble. Not sure how long that will last though, with all the corruption down there!

Outside the flat was a little pond with some birds, reeds and river rats. His place had a little trail to a lake nearby that we walked, and we saw some black-necked swans and some random trains in a park. We got back and we had some pasta which Eric had learnt from some Italian recipe book he picked up, which in turn inspired me to do more work on my Spanish with the duolingo application.

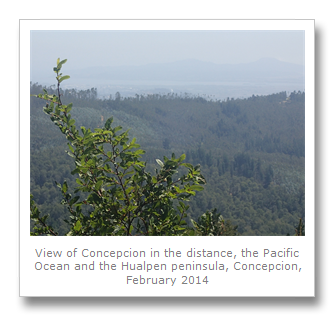

The next day, Sunday, we all decided to head to a protected reserve called Reserva Nacional Nonguen which ended up taking ages to get to, because no buses run all the way there (need a car!). The reserve was nice enough, not too expensive, and was good exercise to walk around. There were about four trails there, and we decided to walk up to the one with a mirador, or viewpoint, which looked back on Concepcion and the Pacific Ocean.

Although the city is located at the mouth of the river, right next to the Ocean, Concepcion was spared the tsunami that resulted from the 2010 quake, although the quake did move the city 3 meters to the West. Since it was founded (by Pedro de Valdivia) in 1550, the city has been razed several times by huge devastating earthquakes but is constantly resurrected to live another day. Why they keep choosing the same site to live on is something I do not understand. Perhaps it is because this was the site where Bernardo O’Higgins proclaimed independence in 1818. This historic event is marked at the spot where it happened, in today’s Plaza de la Independencia by a large stone.

We hitch-hiked back into town and grabbed some beers, and the next day, Francesca and I jumped on a bus heading further South to an old mining town called Lota which was founded back in 1662 but is now just another part of the growing Concepcion. Our first stop was an old coal mine which was built on the coast in the 19th Century to exploit a rich vein of coal that was found nearby under the Ocean. The local buses drop you off about twenty minutes from the mine, so ask the driver for la mina, and then ask for directions when you get down.

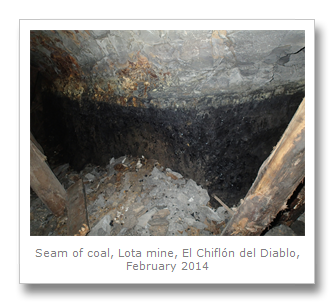

El Chiflón del Diablo, or the Devil’s Blast, was named for the hot and windy drafts that the mine receives. We signed up for a promotional circuit tour which included visiting the mine, a museum, a tour of a park and a look at where the miner’s used to live. No sooner than we had got there, we were being fitted for our miner’s uniform of hardhat with miner’s lamp, complete with a huge battery belt pack. A large group of over 40 people were given a safety talk (completely in difficult, fast-paced Chilean Spanish which we did not understand at all). Health and Safety not being such a big issue in Chile we were allowed to go down anyway. All 40 people, including young children were led off to an old rickety elevator that took us down into a mine which, until recently, had been closed due to extreme earthquake damage.

The mine used to run tours a lot further underground, and although we did go under the Ocean (we saw the water seeping through the rocks above), we did not go as far down as the published information tells you (only a few hundred metes, at best). The whole tour was in Spanish, including a moody bit where the guide/ex-miner (of another mine) got everyone to switch off their headlamps. Most of the tour (for English speakers) was for posing for photos whilst down the mine, and you have to walk out up about one hundred steps, so it is only for the mobile. We did get another Chilean tourist to translate for us afterwards, and he gave us some information, but there are better mine visits in the world so this is most certainly not a must-see.

The mine operated between 1857 and 1990 until the coal ran out. In it’s peak it produced 250 tons a day, so was a huge money-spinner for it’s owners, the Cousino family. They employed over 1500 miners to work in this mine alone, and had many more other business interests aside. The miners all lived at the mine itself, and the wooden community houses they rented survive and can be toured after the mine tour.

Baldomero Lillo‘s book ‘Sub-Terra’ was written here, as well as filmed for a Chilean movie. He also operated the pulperia, or general store, which the miner’s were obligated to use as they were paid in tokens which could only be exchanged there. It is funny how Lillo is now considered a hero of Lota, whereas we can look back as outsiders and see how he was part of a cruel system that totally exploited the miners as indentured servants.

The house we visited was very basic, and a few families would share one house with one room upstairs, and one downstairs. This reminded me of the workhouses in Victorian London where people basically went to die. The rooms would often be separated by cloth hung up by the people who lived there, with hardly any space and almost certainly no privacy. The miner’s sons would be sent down the mine too, and it became a generational prison, with families locked into the fortunes and disasters of the mine. In fact, when the male died (in an accident or from bad health caused by mining) it was up to the sons to provide for the rest of the family. If there were no more males, the family would be kicked out out of their homes.

Conditions were atrocious, with miners only being paid from the time they entered the mine, where they were subject to cramped, dark, and dangerous conditions. Twelve hour days, all week, would leave the men with health issues ranging from poor eyesight, to deadly lung infections.

Our kind Chilean interpreter and his friend (a priest) gave us a ride to the town’s center, which was good, because there did not seem to be any reliable public transport from the mine. The history museum in the center of town tells more of the story about the mine’s corporate owners, how the town came to be, and also about the role that women played making ceramics. The guides are young girls dressed in period costume who can explain a lot about the exhibits and histories.

They also had some of the miner’s equipment and pictures of the guys themselves at work, covered in dirt from head to foot. It made me glad I chose web development instead.

The museum was the house of the Cousino family, and when Luis Cousino died (ironically from tuberculosis which is a lung infection that many of his miners would have suffered from), his wife (and cousin) Isidora Goyenechea inherited the wealth. She spread it around a bit by building roads, a hospital and even commissioned the first hydroelectric plant in Chile.

We sat outside and ate our lunch before we jumped on a guided tour (by one of the costumed ladies) of Lota’s park where the Palacio de Familia Cousino was located. It was Isidora Goyenechea who designed and developed the park and the palace it used to contain (destroyed by earthquake damage). The tour took in a stroll past caged peacocks, cockatoos, some nice gardens, including a part with lots of roses. My favorite part was the view over the bay of Lota, where we could see where the coal used to be loaded onto ships.

We were again lucky when we left because we got a ride with the manager of the Lota tourist circuit, who overheard us asking for directions. He took pity on us and dropped us at the bus stop we needed, and we headed even further South to go see the old Chivilingo hydroelectric power station (the one Isidora Goyenechea had commissioned, Thomas Edison designed, and German company Siemens then built) which was ruined by earthquakes. It had operated for 78 years until the 70’s but now was a pain to get to, and when we finally got there, all that was left was an over-priced filthy campsite next to a building that was in such dangerous disrepair, we could not get too close to it, let alone actually enter it.

The power plant used to have tours, according to local information, but this is no longer the case – no-one goes there anymore, and the most interesting thing we saw was a rat. As Chile is in the grip of a huge Hantavirus crisis from rats, we decided to leave – 15 people have died so far, so staying at this campsite is either for the very brave, or the very stupid. Also, it is about a 4 kilometer walk from where the bus drops you off to the plant, which was totally not worth it for me – but if we never went, we would never have known.

On Tuesday 25th, we headed into Concepcion itself. The pollution is extremely bad in the city, and its surrounding metropolis. As the city expands and more and more factories pop up, this does not seem to be changing in the future.

Our first stop was Plaza Independencia, the site of O’Higgins’ declaration. Funnily enough, the tourist information sign points the exact opposite direction than where it is. When I mentioned this to them, they said they knew about it – guess they were not too interested in fixing it though, so we did not expect much good information and were not disappointed. Useless.

We did see a statue of Mapuche leader Lauturo and Spanish governor Pedro de Valdivia. Lauturo was a young Mapuche commander in the Arauco War which was between Spain and the indigenous people. Lauturo’s military tactics stopped Spain in their tracks, with numerous military losses and deaths. He learned this from his Spanish masters after he was captured and made a servant. After escaping, he taught his fellow Mapuche warriors how to ride horses and better tactics and formations. They inflicted many defeats on the Spanish before a surprise attack saw Lauturo killed. A legend even says it was Lauturo himself who put Pedro de Valdivia to death, but no-one really knows what happened.

Our next stop was the Universidad de Concepcion, where they have a nice art gallery, called casa del arte. The gallery is a huge attraction, because it has some good examples of Chilean art, and also boasts a 300 square mural painted by Jorge Camarena. This acrylic piece (on stucco) is a representation of the history of Latin America, showing how the new world was born in blood during the Spanish conquests. The brotherhood of the countries, particularly Mexico and Chile are symbolized, along with the many identities of the indigenous people.

There were some other cool pieces of art, including a temporary satellite art exhibition, which used satellite photos and imagery, some of which were quite cool.

It was an extremely hot day, but we decided to head down to the next place by foot – a nice walk along an avenue to Parque Ecuador. This park was a bit of a disappointment – just some dumpy playgrounds and spotty teenagers making out, but we made our way to the Galeria de la Historia de Concepcion, and this cool little museum/gallery did not disappoint at all!

The gallery is basically the story of Concepcion’s history back to pre-Hispanic times portrayed solely in dioramas with figures depicting each poignant moment. From the battle of Andalien where Pedro de Valdivia and his 200 men massacred a Mapuche force of some 20,000 with their superior firepower in February 1550, through the signing of the delaration of independence to the 1960 earthquake which devastated the city. The dioramas were all really well made, and looked really cool. They were created by the artist Rodolfo Gutiérrez.

We left the gallery and decided to head out to only other museum in Concepcion we had heard about, Museo Halpuen. This museum was yet another long bus journey outside the city to one of the outlying regions of Concepcion. Annoyingly, there are no direct buses there (get a car!), so we had to hitch from the main road most of the way there.

The museum was built by Don Pedro del Rio Zanartu, who was a writer, farmer and whaler who lived in the North of Hualpen, a peninsular in the North of Concepcion in 1840. When his second wife died during childbirth (the first went the same way), he decided to travel the world. He made four voyages, and each time he added to his collection of art, curiosities and exotic objects from all over the world.

All these objects are now in the museum, including information about the four voyages. We could not take pictures as the museum assistants buzzed about stopping everyone, but we did see lots of interesting things. These included copies of Bolivian shrunken heads, a samurai suit of armor, Chinese pottery, strange weapons (a crocodile knife, literally made from a croc, scales and all) and even an Egyptian mummy Don Pedro had bought in Egypt!

It was a shame that we arrived so late in the day and without a car, because the museum was just a first stop on a circuit around the peninsula which comprises of Parque Halpuen. The road goes around the peninsula down the coast and takes in sights across the ocean, with birdlife, fishing, trails and more. We did not have the freedom to do this, though, so we arranged with the employees to give us a lift back to the road when they all knocked off, and we just got a bus back into town, and then back to San Pedro.

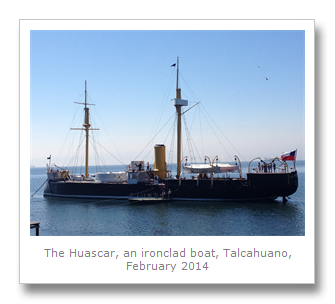

Our last day in Concepcion was Wednesday 26th February, and we decided to travel all the way across town to the North again, but this time to Talcahuano. We got to town, found our way to a bus which said ‘Base Naval’, and got on it. A long time later, we finally arrived at the end of the line, which was next to a ticket office for an old British-built Peruvian ironclad ship called Huascar. This ship was captured by Chile in the War of the Pacific.

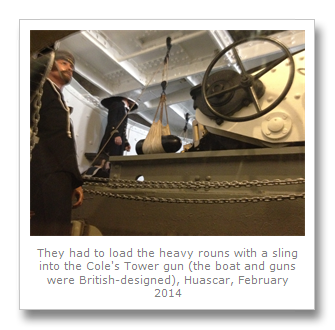

For 2 dollars we got access to the ship which was moored a short way offshore. We boarded a floating wooden pontoon which was pulled across by Chilean naval grunts, and we were welcomed aboard. We were left to our own devices on the ship, which was nice because it gave us time to decode the Spanish-only exhibits.

The War of the Pacific began when Chile began occupying Bolivian land in and around the Atacama desert. At the time, Bolivian lands made it as far as the sea, and they wanted to keep it that way and so fought back against Chile – at first with tax increases, then with arms. Both Chile and Bolivia demanded that Peru either declare neutrality or join the war, respectively, which it declined to do. Chile did not waste time – they declared war on Peru also! These strong arm tactics worked, and Chile ousted Bolivia out of the desert which Chile holds today, making Bolivia land-locked and crippling the country (it is the poorest of South America today). Chilean forces then marched on Lima, and held it. Forcing Peru to also capitulate, and give up even more land.

Although the war was fought mostly on land, there were some naval engagements, and in the battle of Angamos, the Peruvian ship Huascar was captured. Her captain, Rear Admiral Grau, was killed by shelling of the ship by the Chileans. The Peruvians tried to scuttle the ship, but failed, and so the Chileans drafted the Huascar (named after an Incan emperor) into service for themselves.

There were personal affects from her commanders, and also a letter from Grau to a widow of a Chilean officer who he had killed in the battle of Iquique several months earlier. Arturo Prat was the Chilean commander of the Esmerelda, which was sunk at the end of the battle after the Huascar had rammed her three times. In his letter to Prat’s widow, Grau commended the morality and heroism of his rival, enclosing his personal affects, some of which were now on display on board.

To this day, Bolivians still feel they should have their coastal areas back – but Chile is sticking to it’s guns, and the map does not look set to change. Seems to me that Chile overthrew the yoke of Spanish imperialist oppression, just to replace it with their own brand.

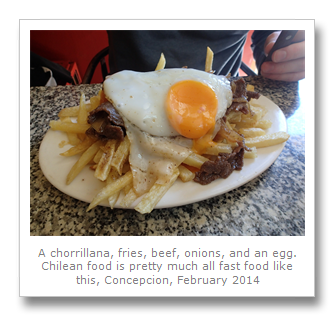

We left the boat, and headed back to our host’s apartment to get our stuff, and then went back into Concepcion (by another goddam bus) where we got some lunch. We stopped at a greasy spoon café, where I ordered local special chorrillana, which is basically fries, fried onions, beef and egg. It tasted delicious even if I did put on a pound or two. We boarded the bus to our next destination (Talca) with full stomachs.

No comments:

Post a Comment