The Pastaza department is located in Eastern Ecuador and it’s capital, Puyo, is the administrative and political capital of the area, and is one of the country’s fastest growing cities.

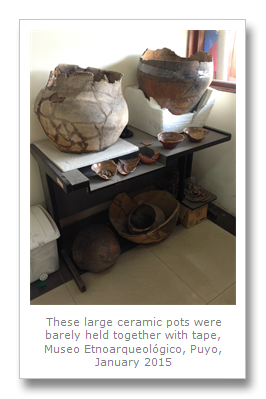

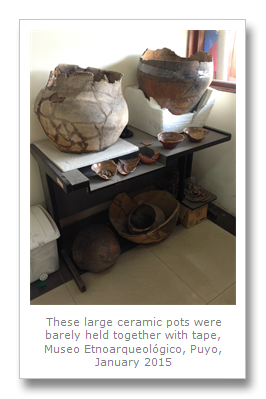

We found a simple hotel in Puyo’s busy and dirty center, and after a small investigation we headed out into the small city. We went over the road and sat down in a chifa, which is a knock-off Chinese restaurant popular in Ecuador and Peru both. After some cheap grub, we headed a few blocks down to the Museo Etnoarqueológico, which was basically just a room of curios and antiquities, run as an extension of the local university. We did not learn much, but the number of big Cat skins, such as Puma, Jaguar and Ocelot hanging up all over the place was pretty depressing.

The museum was really tiny, with almost no explanations in English or Spanish about anything in it. Ceramics lay scattered about cracked and broken, and many displays looked like they had never been cleaned or put back after the last earthquake! The awful taxidermy must have been done by a rank amateur many years ago, and it was not the big Cats who were the only ones to suffer either. Giant Anteaters, Anacondas and Giant Armadillos were all represented by the skins. And no natural deaths here either as the buckshot wounds in the Puma coats testified to.

After this we jumped in a taxi and headed over to the University Museum on the other side of town, but it was semi-permanently closed. Another site we had heard about called AMWAE was also closed permanently – this was supposed to be an artistic co-operative set-up by Huarani women, but apparently it was no more.

Our last disappointment was a planned dinner at El Toro Asado, a BBQ place that we had heard served quanta – a rodent that was supposed to taste like pork. This was also long-closed – proof, if ever any were needed, that Ecuador sorely needs a better tourist board.

We had better luck the next day, the 24th January, when we headed over to a botanical park called Omaere which gave us a guided tour around some reforested rainforest. We were joined by the owner, Chris, who was a hippy biologist from the States who had married a Shuar woman sometime before. He said he had been working in Ecuador for 24 years and was now dedicated to the Omaere park and the projects undertaken there.

Entrance was free (they guide for tips), and the tour was very informative indeed. After meeting Shuar people in Macas, it was nice to get an English speakers explanation of the tribe, particularly an ex-pat who was married to one!

Chris first showed us some Tent Making Bats which had bitten through the vein of some banana leaves, thus folding the leaf over forming a sort of tent shelter (hence the name of the Bat). The Bats were huddled underneath the banana leaf that they had manipulated.

Next up was the eco part of the project, which was Chris’s dry toilets. These babies separate numbers 1 and 2 removing them away to be naturally composted by the ground. Can’t see it catching on in the city, but Chris was crazy about them – “they are the future”!

A nice tour then around the jungle trails – completely regenerated from cattle pasture land! Now the secondary forest was populated by loads of trees, including many with medicinal properties. Chris even told us that his wife was practicing Shuar medicine with patients who visited from near and afar, apparently through word of mouth only. He mentioned that she had had success with curing cancer and so I asked him about it. He told us about one lady who had visited from the coast with an advanced stage of cancer – Chris’ wife prepared some stuff for her, and after several trips to the park for these natural remedies, apparently she is totally cured – and she is not the only one.

No evidence of this treatment was provided of course, because the woman lived miles away. So what is the cure for cancer? Well, Park Omaere are not going to be sharing that anytime soon. Why? Because apparently the Shuar don’t share their medicine with their enemies – basically anyone from the West who would come and mow the forest down and overuse the medicines there. If they really do have a cure for cancer (which I doubt), then it seems at best pretty dumb not to realize they could sell the cure which could then be grown naturally elsewhere (proceeds could go back into forest regeneration if the Shuar are so concerned about it), and at worst pretty selfish when you realize the world is in the middle of a cancer epidemic.

In fact, Park Omaere have many treatments for sale, and this seems to be where the park is focusing it’s efforts these days. Much of the tour was pointing out plants and trees used in the natural medicine of the Shuar. No doubt this is where modern medicine is from, and the home remedies of the Shuar certainly have a huge value – and it is extremely important to retain the knowledge they have gained and passed on over generations. The tour did become a little tired though when our biologist guide starting asserting that Shuar men can take these “big medicines” and astral project themselves across large distances and speak with people many miles away. Stick to the facts guys, not the hogwash paganism. We know drugs make you real high, and you can feel you have flown and stuff, but they are just chemicals after all.

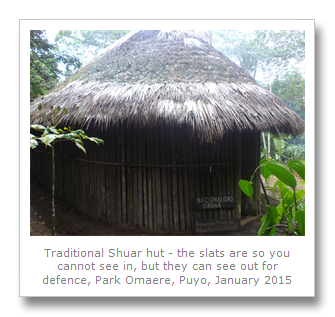

The better aspects of the tour were the more factual and historic information about the tribes in the region. The Shuar, the Huarani and the Kichwa peoples. We were shown Shuar tools, such as nets and spears made from local trees from the jungle. We even got to see some traditional style Shuar and Huarani huts that they had built in the park.

The Shuar people used to be known as savages (Jibaro), and were the headhunters we learnt about when we visited Cuenca. We met a Shuar family when we visited Macas and we can testify that they don’t do that anymore! They now live in scattered communities with schools, plazas and fairly decent houses. There is a thriving trade in tourism amongst the Shuar communities, and they even have political representation through the Shuar Federation. In the past the Shuar used to live as individual family units scattered throughout the forest. Each house would be at least several kilometers from any other and would be populated by one guy with all his wives and children. They were egalitarian, having no leaders, but they did have shamanism and ritual.

When a Shuar man was married off he would leave his home and move in with his wife’s family. Men would weave and hunt whilst women would tend the gardens. Chris showed us the formal introductions that the Shuar would initiate if they went to visit each other – men would have to stand at the very edge of another man’s property and call in a special way and then wait. They would always carry their long bamboo spears and blowguns with them – and when their neighbors came to answer any visits, they too would be carrying arms. If a visitor got no reply, he was not allowed to advance any further, as any unpermitted approaches would be met with violence.

In fact, the Shuar are well known as a warrior race. There is even a special wing of the Ecuadorian special forces that were reserved for Shuar warriors, and they specialized in jungle lore (although this is now opened up for non-Shuar applicants).

The Shuar would only visit each other when necessary. To sue for peace during feuds, to ask for help, report complaints or to forge alliances. Historically they have managed to form armies, however, so they were by no means defenseless. In 1527 they defeated the Incan advances – the Incans never conquered them. Then in 1599, after attempts at taxation, the Shuar then kicked out the Spanish too. Unconquered, they eventually fell to Evangelist and Catholic missionaries and came out of the jungles to centers where they now live. Because of these centers they have managed to somewhat successfully defend their lands from the state, but in most cases they have completely lost their traditions, knowledge and culture.

It was cool walking around the park and asking Chris all kinds of questions about the place. His wife and several other Shuar women bought the place 16 years before from the cattlemen and have been developing and refining the project ever since. The regeneration was so successful that we were told they even had a Jaguar roaming around for awhile. This was surprising seeing as the park is located in a little crook on a river, and so access would be difficult – and besides, Chris said, the neighbor shot it a few years ago. Typical.

The tour ended with the guide trying to sell us some medicines, but we got bored and so left. All the medicines seem to be based around urine therapy along with two types of trees – sangre de drago (dragon’s blood on account of it’s thick red latex sap) and unas de gato (cat’s claw after the shape of it’s thorns).

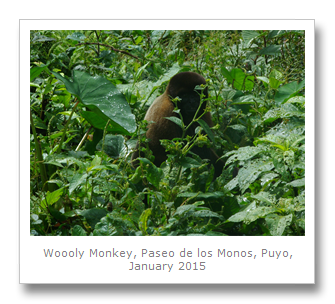

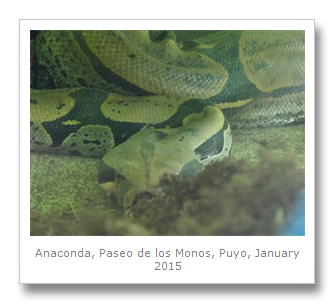

We left the park with a couple traveling with their young son and shared a taxi with them to an animal reserve nearby called paseo de los monos (Monkey’s path). There sure were a lot of Monkeys at the ‘reserve’, including Wooly Monkeys, Spider Monkeys and Capuchins – but it was pretty obvious that this was just a zoo and the Monkeys were a permanent fixture. The coolest animals though were a large (caged) Anaconda, and a curious Coati that followed us around.

Our next stop was, again by taxi, to the Jardin Botanico las Orquideas. This family-run reserve was again repopulated from cattle pasture and made into a natural reserve in which the owners guide you around. They focus more on the natural world though, and specialize in showing guests their huge collection of natural orchids. Some were so tiny they had to be viewed through a handheld microscope.

There was an exhibit of photographs taken each year since the reserve’s inception in 1980. The photos show the different animals and plants that the owner found as the forest grew back over the time. It was nice to see some larger mammals finding their way back into the place towards the later years of regeneration. A really great plant our guide showed us was wild garlic which, when you ball it up and rub it on your fingers, smells very nice - of garlic!

We got the bus back from the botanic garden reserve which was easy and much cheaper than the taxis. The next day, the 25th January, we went to a local exotic bird reserve (Parque Real de Aves Exoticas). It was quite a shock to see that what Ecuadorians call an exotic bird reserve, for us, is not quite so exotic. Chickens, pigeons and pheasants were the order of the day. Anyways, many of the birds were very pretty, or were just so huge that they were still interesting to look at.

One thing we definitely noticed in Ecuador was the outstanding beauty of it’s natural world. Loads of birds, forests and other landscapes – the cultural side is extremely interesting, and if you put a little effort in, it is quite accessible too.