We travelled down from Huarez to the desert town of Casma in a shared taxi via the high Callán Pass. For once the driver drove sensibly so we actually could enjoy the beautiful scenery as we trundled by each Andean village, from the Black Mountain Range towards the coast. We arrived in Casma on the 30th October, and the driver dropped us off a short, but extremely hot walk into the center. Francesca had the idea that we should try and do a journey all of the way across the country from the Amazon lowlands in the East, across the Andes, to the deserts of the coastal regions. We resolved to try this one day, whilst we settled into the comfortable Hostal Las Dunas, a few blocks from the main plaza.

The Casma Valley is located in Peru’s region of Ancash whose principal economic activity is mining. It is also the most productive coastal fishing zone in the country, and produces a huge amount of crops along it’s fertile valley floors. Local tourists head to the popular beach fronts, whilst the other main draw for tourists are the numerous archaeological attractions crammed into the area from every different point along the timeline of human habitation. Francesca and I frequented a couple of tourist restaurants and tried some of the local grub – such as cebiche de pato, seco de ternera, papas a la huancaina, and picante de cuy.

After a good night’s sleep, we took a moto-taxi (rickshaw) to the nearby Sechin Complex, and we began with a walking tour that I had put together for Francesca, starting in the Max Uhle museum of archaeology. Uhle was a German (1856 – 1944) archaeologist who worked on many sites we had already visited elsewhere. He was the first person to describe the Chinchorro mummies, he published a book about the ruins of Tiwanaku, and his work excavating and writing about the Moche and Chimu cultures, is still taught in South American archaeological schools today.

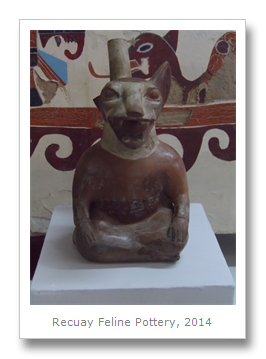

This museum, located a short journey from town in the Sechin Complex itself, was pretty informative and interesting. It showcased several sites from the Casma valley itself, such as Las Aldas, which dates back to about 1800 BCE, and Mojeque, which was supposedly a religious site about the same age. There has been a lot of confusion over which site belongs to which culture, and even the late but great Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello identified the wrong cultures with sites that were in fact much older. Many ancient cultures are arbitrarily named by archaeologists looking to make a name for themselves, and so cross-over and overlap was inevitable, especially as sites were reused over thousands of years by different cultures. This left a confusing mixture of different styles of architecture and art from different times, often side by side at the same sites.

Of course, to make matters worse, there are no ancient written records as writing was never invented in pre-Columbian America as far as we know. As such, the names for these so-called cultures are not even what those cultures would have called themselves. Many cultures are just named after the region that they were first identified in, and so many cultures now have Hispanic names.

Scientifically identifying a new culture is sometimes as simple as identifying a new architectural style, even if it is clearly influenced by other styles. A clear separation of these cultures then seems a bit arbitrary, and even misleading, especially when it is obvious that we have absolutely no idea if these cultures had any clear lines of division such as borders.

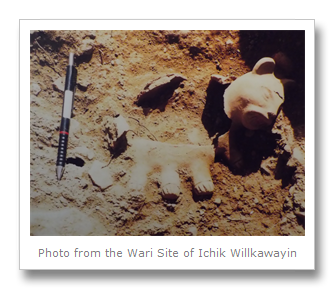

The dry and windless desert conditions have helped preserve these cultures, and they have managed to survive multiple El Nino events. Grave robbers have taken much of the evidence that was left behind, but the archaeologists, and now crucially, the modern governments are helping preserve what is left. From this evidence, we can actually tell surprisingly little, mostly from graves, especially as the Incans and Spanish and Peruvians have all built on top of whatever was left behind.

Carbon dating tells us how old things are, more or less, but it seems that archaeologists are all too eager to expound on their theories about the cultures and their behaviors, even when there are numerous possibilities for the reasons that evidence exists. That is not to say that I think there should be no narratives in the museums in Peru about these cultures, but they should be presented as theories, rather than as known fact.

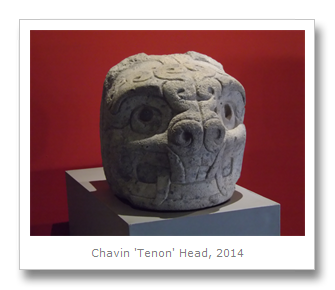

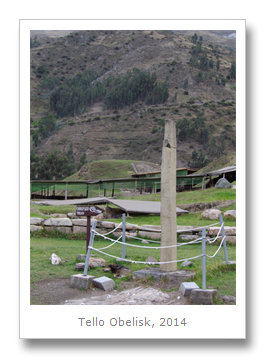

For example, in Huarez, we learned all about the Chavin culture, and for many years it was thought that this culture was the oldest one in the Western Andes, with it’s capital of Chavin de Huantar built around 900 BCE. Many of the museum information boards still explain this as fact, when it was proven in the early 21st Century that there was another, older civilization called the Caral Culture. This finding was unsurprisingly mired in controversy, and bought about ethics reviews from both the Peruvian and US governments, charges of plagiarism and exposed the archaeologists involved as extremely greedy, egotistical and self-serving.

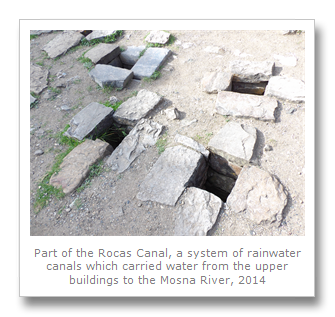

Further exposing these ‘facts’ as merely theories, in 2008, another ‘oldest’ site was found, this time in the Casma Valley. This site had previously been described by Tello as being built during by Chavin culture, but the new findings in 2008 actually found they pre-dated all known civilized cultures in Peru. The Sechin culture was born, dating back to 3500 BCE, hundreds of years before the Caral and Chavin cultures.

Sitting on a granite hill, Sechin has been excavated since being discovered by Tello in 1937. Work at Sechin Bajo (Lower Sechin) began in 1990, but it was not until 2008 that the really old stuff was found. Depending on who you ask, this site is actually not open to the public yet, although it is more than likely that you can pay a few soles to the local people who own the site, to sneak a peak. Because of the controversies, politics, corruption and also environmental concerns about the sites, there were no archaeologists working at the site at the time we were visiting Casma, but we never made it to the site.

The part of the complex which is open to the public has some mud and adobe huts dating back to 2500 BCE. The site was used for a thousand years, with numerous different levels added to it over time. The main building no longer looks like much, but pottery from the time shows how the roof used to look like.

The most outstanding icon of this culture are the bas-relief carvings on a façade on the outermost wall of the building. Men who are believed to be warrior-priests holding weapons appear alongside their seemingly defeated enemies, who are mutilated and beheaded beyond repair. Again, different theories exist as to what this all represents (a battle? a revolt gone wrong? a ritual?). It looks like a rendering of a battle to me - the building itself turned memorial.

Nothing is known about this culture, but much is believed. How different they were from their contemporary Chavin neighbors, or how similar, may never be known. Are they simply Chavin by another name? It seems like the sands covered over these buildings, and these cities, only to reveal them again centuries later to remain a mystery.

We walked up the road (try and get a taxi rather than walk) to the Sechin Alto (Higher Sechin) site. This is a little more difficult to find, as it is just a huge mound of dirt now, next to a cement factory. The Pan-American highway splits the site in two (so much for conservation!), but you can walk around, for free, and try and find bits of pottery and shells.

We saw some owl burrows, multiple fires from the surrounding farms, burning away the foliage or the trash on their land, but not much to indicate a huge and vast culture lived there. The Sechin river, from where the culture gets it’s name, made its way peacefully through the Sechin Complex. The similarity of architecture and proximity with each other are the evidence that Sechin Bajo (5500 years old), Sechin Alto (3500 yeas old) and Cerro Sechin (4500 years old), all belong to the same culture. An excellent article about it is on Ancient Wisdom.

I didn’t think Sechin Alto was worth the walk, but Francesca liked visiting it. I would recommend going with a guide though. After we made our way back to town, we ran into Renato who runs Renato Tours. He is definitely the man to get in touch with if you are visiting Casma (his cellphone was 943-636551).

We sorted out a good price with Renato to take us to three sites over the next two days. On the 31st January, we visited my favorite site in the area, Chanquillo.

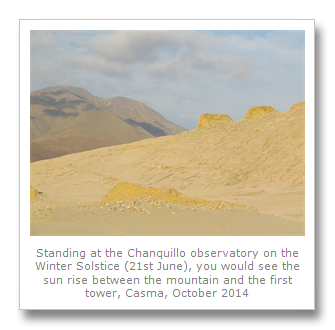

Built around 400 BCE by an as yet unnamed culture, Chanquillo is best described as a fortified city and observatory. Possibly one of mankind’s earliest attempts at marking time with a calendar by charting the sun’s progress, the observatory at Chanquillo is an awe-inspiring site to visit.

Thirteen stone towers sit on top of a natural ridge acting as markers. Observers at the observatory building below would gather and watch the sunrise. It’s position between the towers would indicate what time of year it is. The Summer solstice, for example, is December 21st, and that is when the sun would be on the extreme right of the last tower. The Winter solstice is the 21st June, and that is when the sun would be at the left of the first tower. These principles still apply today, and this rudimentary, yet extraordinary calendar, endures.

Although the language, art, rituals and belief system of the people at Chanquillo have been forever lost, their buildings still remain behind. If they didn’t, all trace of them would have disappeared. The thirteen towers are an awesome site from the fort/city above, sitting down on the desert floor. It is an indefensible position, with no water source, so the natural ridge on which the towers were built must have been the only reason they put it all there.

The fort itself was really a collection of rocks which were dragged all the way from the distant riverbeds, and arranged in circles around each other. The two entrances/exits would have been defended from positions above, like any castle. Most of the fort has collapsed due to weathering and earthquake damage, and we had to be careful not to lose our footing over the sharp rubble.

We found lots of bits of ceramics and old shells on the desert floor, but it was quite a bit of a walk to get down to the observatory and back. We made it back up though, pretty exhausted, and headed off to our last stop of the day, a much more recent site called Manchan, build by the Chimu culture. The Chimu culture lived all along the coast, but much later than the people who built Sechin and even Chanquillo.

It is thought that Manchan housed around 2000 – 3000 people, had its own water channels, and was one of the last strongholds of the Chimu people before they were overrun by the Inca. Nowadays the thing that strikes you most about this site is the holes leftover from the huaqueros. A small illegal settlement has also been established at the base of the site by peasants who have claimed this as their own land. Seemingly, not much was found at Manchan, probably because of the grave robbers and squatters who have looted the place. Further destruction was caused by the Pan-American highway which runs straight through the middle of the site.

We saw lots of burrows, which our guide assured us were from Burrowing Owls. Many pieces of human and animal bone were smashed all over the desert floor where the robbers had left their holes. We found smashed ceramics everywhere, and it was sad to realize how much of the information that this site could have yielded up has been lost and stolen forever.

We left with plans to meet the next day to go and see another site believed to be from the Chimu era. The Pampa Colorada geoglyphs apparently match Chimu designs on ceramics that were found, but it is not clear whether this really dates the geoglyphs accurately as Chimu or not.

The climb up was steep. The geoglyphs are located near an old Inca Trail, and the area is totally un-signposted, so a guide is definitely necessary. A steep climb up leads to a moderately good view of the geoglyphs, but it is really only viewable in totality from the very top, which took us about two hours (up and down).

The geoglyphs are viewed from the side angle, and it is difficult to make them out. You can see a human figure though, which looks strikingly like the reddit alien.

Above this is a frog or toad, which is the largest figure. You can also see a camelid and lots of circles all around the man. These lines were built in the same way as the Nazca lines – by removing the stones and rocks on the desert floor to expose the reddish color of the sand and dirt below.

The man is also very similar to the figures of people found at the Palpa lines, in Nazca, and it is difficult to believe these geoglyphs were done by different peoples, at such different times. The Nazca culture is dated from 100 BCE to 800 CE, whilst the Chimu are placed in the time between 1100 CE and 1470 CE.

Whatever the case, it was really awesome to see what remains of these ancient cultures in and around Casma. If Peru would invest more money into the tourist infrastructure in the North, along with protection for these sites, they would easily rival Egypt in their interest, especially if the archaeologists can get over their petty jealousies and egos and work together on trying to build up a picture of the past everyone can learn from.