We arrived in the town of Chaitén by bus on 28th January. A short three and a half hours by minibus from Futaleufu, we were happy to see paved roads again. However, we did not quite know what to expect to find, as stories about Chaitén’s status abound on the road. Rumors and backpacker gossip are not helped by out of date guide books proclaiming Chaitén as a ‘ghost-town’. In the massive eruption of the nearby Chaitén Volcano in May 2008, the town itself was completely destroyed. Volcanic tephra (ash, cinders and small super-heated rocks) blocked the nearby Rio Chaitén, diverting it into the town and flooding it with the thick grey ash-filled sludge. In fact, the volcano had not blown for 9500 years, but is now still in an ‘eruptive phase’ since causing mass evacuations across the region. Online reports even state that Futaleufu was covered in a large amount of ash, and it was evacuated also; but we never saw any sign of damage there, and no-one mentioned it all – probably because the Futaleufu residents do not want the fragile tourist industry to be adversely affected with the same type of rumors surrounding Chaitén.

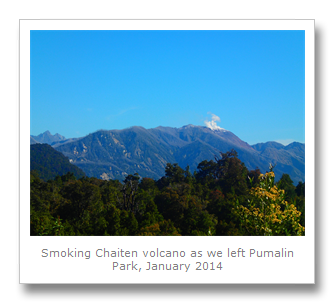

The truth is, as of the 31st January 2014, Chaitén is pretty much on its knees, but it is slowly starting to stand again. It has functioning services, like numerous residencial and hospedaje accommodations, a tour agency (Chaitur Excursions) and supermarkets. On the whole the volcanic ash that covered everything has been cleared away, and the roads are good, the ferry port across the Corcovado Gulf is working (infrequently) and it is almost business as usual. Before the explosions, there were about 4000 people, but now there are less than a thousand. Many houses stand vacant. With broken windows and heaps of ash in the front yards covering vehicles that were in use up until the volcano clogged their engines and everything else, they serve as a reminder of how close the town was to being wiped out. The volcano is visible on the rare days when the clouds lift and the rain stops, with its 3km wide lava dome still pouring it’s lethal gases all across the sky.

We had expected to arrive much later due to the state of the roads we had been on, so we unexpectedly booked on a tour of the Pumalin Park private nature reserve next to the town. We had barely enough time to get some food, and store our bags with the the agency – the aforementioned Chaitur Excursions before heading off again for a full day in the reserve.

Located to the North of Chaitén, the Pumalin Park reserve actually contains Volcano Chaitén along with Volcano Michinmahuida. The park was closed after the eruption for over two years until late 2010 whilst they affected a safe clean-up, further adversely affecting the economy of the region. A huge fault line runs under the two volcanoes, which also produced some minimal earthquakes in 2005, a precursor of the destruction to come.

Our first stop was to see the Volcano Chaitén Trail, or at least the first twenty minutes of it. It was a rare sunny Chaitén day, and the first thing that struck me was the large number of horseflies around. These annoying huge flying currants actually bite, so I killed as many as I could whilst I was there.

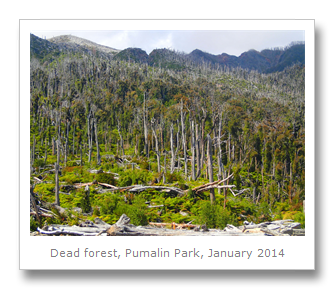

The trail runs through some Valdivian rainforest which had no large trees. After about ten minutes, the trail opened up and we could clearly see why the trees were missing – the volcano had left a huge trail of destruction all over the mountainside. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of trees were just grey stick-like dead things sticking out of the ground. One side of one mountain facing away from the volcano was covered in verdant and lush rainforest; it’s other side, facing the volcano, was grey death.

The eruption started on May 2nd 2008, and evacuation of all but a few hundred stubborn residents was completed by the next day. Water supplies were completely contaminated by a 30 mile high plume of ash landing down around the region. Satellite photos show the ash reaching across the continent, pushed by the Pacific winds all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. On May 6th, the volcano completely exploded, sending pyroclastic flows down the side of the mountain, which, when mixed with the nearby river water, created lahars (volcanic ash mixed with water creating thick, sticky mudslides). These lahars clogged up the rivers, which subsequently killed the trees and destroyed the town. The tephra was extremely hot, and the cinders burnt vegetation and trees alike. It was amazing to see such devastation, especially caused so recently. After about half hour, with the guide explaining everything in Spanish, we moved on. Francesca and I resolved to return to the trail and go up to the crater, from where you can stand next to the smoking volcano caldera itself.

The next stop was a short trail leading up to a set of beautiful cascades in a steep-sided narrow canyon. The other members of our tour groups were a Chilean family with children, and some other backpackers on their own. It was a fairly easy tour to go on, and very diverse, helping showcase the natural diversity of the park itself.

Our next stop was a big draw for many people – the Alerce Trees Trail. We had previously visited Los Alerces National Park in Argentina where we had seen two small Alerce trees, and this was our opportunity to see some of the oldest examples of this tree on the planet!

The trail was very easy, with lot of wooden stairs and handrails to help over the forest floor. Eventually we came to a grove of really old Alerce (Patagonian Cypress) trees. These bigger specimens were extremely impressive – much more interesting and awe-inspiring than the smaller ones we had seen in Argentina. There were numerous trees here, and it is really good to see that over 80% of the Alerces here survived Volcano Chaitén. At the end of the trail there were even some clearly over 3000 years old. Over 60 meters tall, these are some of the largest trees in the world. The oldest Alerce was 3622 years old, which made it the second oldest tree in the world, verified by counting the rings of the trunk.

It was amazing to see how different this ecosystem looked compared to the ones just down the road in Futaluefu, Puyuhuapi and Coihaique. The colors, shapes and mixture of the trees are different in each area – it made Francesca and I realize how important it is to protect these areas as National Parks from further exploitation.

Pumalin Park is the largest privately owned park in Chile (3250 kilometer squared), and is operated as a free access public park based on sustainable touristic and economical values. Opened in 2005, it was donated by Doug Tompkins, an American tycoon who has caused lot of controversy by buying up large tracts of land in Argentina and Chile and turning them over to the government as protected areas. He was the co-founder of outdoor equipment and clothing firm The North Face and Esprit respectively, but sold it all off to become the environmental philanthropist he is today. He also owns the private reserve in the North of Argentina we saw a little of; the Iberá Wetlands.

There are many who do not want Doug in Chile at all. There was widespread panic over his accumulation of so much land. Politicians and business have exclaimed that he has ‘divided our narrow country’, as the park stretches from the West coast to Chile’s Eastern border with Argentina. The anti-Semitic military have claimed that it is a Jewish conspiracy to stop Chile from progressing. In reality, it is really just the logging and hydroelectric companies who have a problem with Tompkins, mostly concerning his activism against those same companies who have polluted rivers and destroyed huge parts of the rainforest already. Doug Tompkins apparently spearheads the anti-dam movement of Patagonia sin represas.

In the afternoon we had finished our Alerce Trail walk and all got back in the minivan (away from the hideous flies), and trundled along back to another, bigger trail called Cascadas Escondidas. There was one of the park’s numerous campsites here, and we stopped to eat our lunch. Francesca and I had packed some empanadas (including an apple empanada!), cookies and chips. The flies were still really annoying, but the weather remained good, and lunch was nice.

Afterwards we started heading up. And up. And further up. Up a large number of wooden steps, we reached a turning point and went right over a rickety looking wooden bridge. We eventually came to steps leading down. This came to a beautiful opening where a twenty meter waterfall was crashing down into a hidden pool surrounded by huge cliffs.

Back up, and there was another longer trail to the higher waterfalls. These were a little further away, but still pretty impressive – and the spray from it cooled us down after the hot and humid walk up hundreds of stairs.

We got a little lost on the way back down, and ended up going past another Alerce Trail on the way back to the vehicle. Luckily, everyone was much slower (must be all the hiking practice we have been getting), and so we waited with the flies until we could get out of there!

On our way back to town we got to stop at a lukewarm natural thermal spring right by the side of the road – but it was pretty yucky from all the plants, so we never got in it. Then, we made another unexpected stop (Francesca and I jumped on the tour without checking what else we were to do) at Santa Barbara beach, between the park and Chaitén town. This volcanic sands beach is completely black, with lots of kelp over the rocks, and a few people dotted here and there, some camping, some cooking, some drinking, some just relaxing.

The brutal flies at this time of year meant we did not want to do any of these things for too long, so we got another empanada from a house near the beach and then all returned to the town.

Francesca and I found some accommodation and then picked up our bags from the agency office. It had been a full and totally unexpected day, but it was a diverse and great tour – well worth the $US40.

We soon found out that our ferry was not available for a few days, so we made the most of hanging out in the town. The place we stayed in was OK – we had learnt not to interact too much with the old ladies who run these hospedajes. The less interaction, the less chance of a falling out. The town was pretty basic in what it had to offer when we were there, but it was comfortable enough (we managed to get our laundry done, etc.).

On the 31st January we decided to revisit the volcano and get a closer look, so we walked to the edge of town (after buying the essential empanadas) and tried our hand at hitchhiking. Luckily we got a lift after about 10 minutes by a tour that was going to the volcano from none other than Chaitur Excursions. We got out at the start of the trail and told the guide we had decided not to do the tour but thanks for the lift. I tried to give him a little money but he was still keen on getting us to come back with them so told me he would take us back when we had all finished for half price. We ended up paying nothing because they were much quicker than us and left before we got back down.

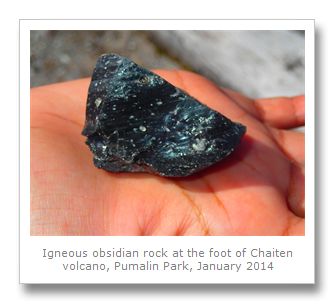

The trail was better than before because the bad weather had chased off all the horrible horseflies that had pestered us last time we were there. Dead trees were everywhere, trunks burnt to a crisp and now just hollow grey shells. The grey ash was all over the floor everywhere, and as we went further up and up towards the volcano itself the ash turned to stones which turned to bigger and bigger rocks the higher we went.

The first kilometer was an easy and relatively flat walk on an easy trail, but after this it started uphill with hundreds of stairs that they had added. It was a climb of over 600 meters along a trail of 2.2 kilometers so it was pretty steep in places, especially near the top.

The view was pretty incredible on the way up, and we saw a huge swathe of destruction that ran down the hill in three directions all the way to the river. All the trees in the path were dead, either burnt by the hot pyroclastic flows, or knocked over completely. Rain started heading our way from the Pacific and we could clearly see it falling a few kilometers away over the land, but we were lucky as we never got wet because it turned away at the last minute.

The last forty meters or so to the top were pretty difficult and scary. One lady gave up, clinging to the ground as if the mountain might collapse all around her! We persisted, and followed the ridge up to the top across loose ash and gravel from the volcano. It was worth it. We had seen the lava dome on the way up, but when we got to the top of the walk we could see it much better. Sitting in the three kilometer wide crater on top of a caldera of burning molten lava, the lava dome is red and black ash and rocks, with numerous fumaroles of smoke plumes springing from all over it.

The bottom of the crater, between the mountain and the lava dome was just grey ash with lots of deep ridges that would make it hard to cross – but that was 50 meters below us. We could clearly see where the volcano had exploded through the side of the mountain right next to us back the way we had come from.

At that moment, once everyone else had left the top, the clouds parted and we got some good picture with the sky really blue. It really contrasted the reds and black of the lava dome, with the white smoke pluming from the top. The surrounding forest was doing its best to return and the greens added to the strange beauty of a terribly dangerous place. If the volcano had blown then, we would have had little chance of escape – although hopefully it might have given us some warning before erupting fully.

The obsidian at the top of the volcano was much bigger than the smaller lumps we had seen at the bottom of the trail – and we even a Chilean hawk, which I got some snaps of.

This was our first active volcano that we had climbed – and it was a difficult climb (especially down – the knees really need help from trekking poles) – but it was totally worth it. There is no fee to enter this park either, and as we got a hitchhike back within twenty minutes from some local in a jeep, the whole visit was free.

We got back to Chaitén around 7pm, and got some food. We were due to leave the town the next day, but both enjoyed our time there. Maybe we had simply learnt how to be around the people on the Carretera Austral. Whatever it was, we hope Chaitén gets to rebuild where it is – the Chilean government have announced their intention to help this happen after a movement to stop the town from being moved elsewhere gained momentum after the people marched on the volcano as a protest!

If you do decide to climb Volcano Chaitén, make sure you pay it respect. It is a difficult climb in places, and I am surprised to find no history of unfortunate incidents online when looking at it. Good luck to Chaitén –the volcano is still active, and perhaps the mountain Gods still need to be appeased.